A Lesson From the Master : Guitar: Classical virtuoso Julian Bream offers a class in perfectionism to a select group of students.

- Share via

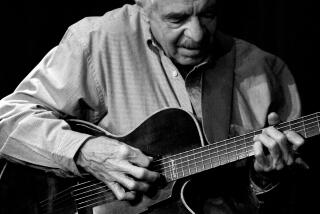

Eight young guitarists sat on folding chairs at the back of a recital hall stage at Cal State Northridge one afternoon last week. Standing in front of them was the man considered by many to be the greatest living classical guitar player--Julian Bream.

Each of the men had won regional competitions in various parts of California to earn the right to be there. This should have been one of the happiest days of their lives.

But they all looked as if they were about to go to the guillotine.

This was a master class, the first Bream had consented to teach in Southern California in more than 20 years. One by one the students would be called forward to sit on a cushioned bench at the front of the stage and play a solo piece for him to evaluate.

The students who had attended his concert on campus the previous night could not have been soothed by what they saw. The sound that came from Bream’s guitar and lute was beautiful. But Bream, who is known as a perfectionist, played with such intensity that it seemed at times as if the instruments might shatter in his hands.

To make the four-hour master class even more unnerving, the recital hall was filled with local guitarists and music lovers who had come just to watch.

Luckily, Bream was sympathetic.

“I know what a horrible situation they are in,” said Bream, 57, as he relaxed backstage after the class. “If they lose their confidence, they can go to pieces. I’ve seen it happen.”

Bream began by putting the men at ease with a few quick stories about his student days, before the guitar was widely accepted as a classical instrument. “I went to college to study the piano and cello,” said Bream, with a pronounced English accent.

“Guitar was just a hobby,” he said, “but it seemed to me that the instrument had possibilities, not least of which was that there was no one else playing it. I could be, as it were, the best boy in an all-girls school.”

The first student to take his place by the master was Kevin Smith of Cal State Sacramento. He quickly did some last-minute tuning and immediately started playing the piece he had prepared, Fernando Sor’s Mozart Variations.

After about a minute Bream stopped him to suggest that, when playing in public, the student insert a significant pause after tuning up.

“You have to get the attention of the audience,” Bream told him. “You have to make sure they know you are starting. You have to achieve a rapport with them on the very first chord.”

During the course of the afternoon, Bream had other bits of stage advice: slightly overemphasize the bass notes, because they do not travel as well out into an auditorium, and when playing softly, pay particular attention to tonal quality or it would sound muddled to the audience.

But the bulk of his teaching consisted of having the students, each of whom had half an hour with him, play certain short passages repeatedly until Bream was satisfied.

Robert Simon, one of four students onstage from CSUN--which, as host, filled half the places--was especially targeted for this treatment.

He had chosen Daniel Bachelar’s “Monsieur’s Almaine,” which begins with a lyrical passage and moves into difficult arpeggios. But Bream made him repeat the introduction more than a dozen times.

“The first part is so relatively easy that I was not concerned about it,” said the 25-year-old Simon later. “I was moving through it to get to the part I had worked hard on. But he would not let me get there.”

After each repeat, Bream pointed out something that was not quite right in the playing of a note, the rhythm or the articulation. Finally, after about 15 minutes, Bream smiled at him and said, “I’m not letting you get much further, am I?”

The line got a laugh from the audience. But Simon got the lesson. “He was showing me that every note counts,” the student said later.

When he played the piece from the beginning again, it was more expressive and focused.

“When I force them to do something over and over,” Bream later explained, “they begin to listen to themselves, which they don’t much do. They are so involved with the mechanical action of playing that they don’t stand back, as it were, and listen.”

Bream worked perhaps most intensely with Walther Quevedo of CalArts, who played Bach’s achingly beautiful Chaconne in D minor.

“This is the greatest piece ever written for a solo instrument,” Bream told the student, a native of El Salvador.

Quevedo played quietly, but with a great deal of feeling.

“I’ve sweated buckets over this piece,” Bream told him. “You need all the experience of a lifetime to feel it. It must be played with dignity and care.”

The young man seemed undaunted by these grave pronouncements. He simply played it several times until the master was pleased. “It sounded good,” Bream said. “It has dignity.”

Bream cautioned the group at the beginning that from each generation of classical guitar players, only a tiny number manage to achieve a successful solo career. In all the master classes he has given over the years--he presides over about four a year in London--he said he has heard only a couple of students who he thought had the potential to become international stars.

Later, he said the standard of playing among the students that day was “very good indeed.” But asked if any of them showed that rare star potential, he at first shook his head no.

Then he paused and added, “Well, there was one player, the one who played the chaconne. If he can deliver more enthusiasm for what he is doing, he may do very well.

“He had something.”

The last student onstage was Trevin Pinto, of CSUN. He played John Dowland’s “Forlorne Hope Fancy,” with a final variation that is fiendishly difficult to play. “That was brilliant,” said Bream, as the young man finished a fast run of notes with a flourish.

Then the master pointed to just one note among the blur of notes in the music. “All except for this C-natural.

“Let’s try it once again.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.