HOTHEADS AND HOLY MEN : CUSTER’S LAST CAMPAIGN: Mitch Boyer and the Little Bighorn Reconstructed, <i> By John S. Gray (University of Nebraska Press: $35; 496 pp.)</i>

- Share via

It seems strange to sit down only weeks after the end of the Persian Gulf War to read a 496-page book that has been heralded as the “all but unassailable,” virtually final word about the Battle of Little Bighorn. Does anyone still care about what happened to Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer and his battalion on that hot afternoon 115 years ago this June 25?

Yet, despite our excessively cozy familiarity with the smart bomb and other weapons of precise and meganumerical destruction, there is still something compelling about the bows and arrows and repeating rifles of Little Bighorn. There is a poignancy about each soldier and Indian (the Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho principally) who fell among the sage-covered coulees and ravines of Montana; and there remains an unresolved mystery about the brief, perhaps hour-long, battle between Custer and Sitting Bull and Crazy Horse that the months with George Bush, Gen. Norman Schwartzkopf and Saddam Hussein can’t really match.

Oil and Middle Eastern turmoil are part of the politics and economics of the moment, but the Indian wars are part of our national mythology as well as our history. Two aspects have drawn writers, poets, film makers, historians and archeologists to the Battle of Little Bighorn. In most accounts these are intertwined, even though one is more the stuff of legend and popular culture while the other at least seems to be the province of fact and precision.

The first aspect is, of course, the figure of Custer, the boy general of the Civil War, the Indian fighter and (in one view) Indian sympathizer, who led his men into the most celebrated defeat in American military history. The other aspect is the enigma of the Last Stand itself. Since there were no Army survivors, since the few observers saw only fragments of the entire action and often left contradictory accounts, what really happened?

Over the years, some professionals and many gifted amateurs have tried their hands. Individual eyewitnesses (usually Indian), an Army court of inquiry, grandmother and grandfather tales, archeological evidence, the archives of shipping and trading companies, local newspapers and myriad other diarists, itineraries and souvenir hunters have been ransacked, arrayed and rearrayed to find out the “truth” of the Last Stand.

This urge for the facts is one reason why so many Little Bighorn buffs (and I must confess I am one) found Evan S. Connell’s dark and moody “Son of the Morning Star” (1984) wonderful but frustrating. There were no footnotes, no way to figure out why he decided to believe one witness here and another there, no sense of what is established and what is debatable. For as every visitor to the battlefield knows, Little Bighorn is the place where myths are anchored in the realities of place and action: If I were in the Indian village, when would I have seen Custer and how would I have attacked? If I were Custer, what was my strategy and when would I have known all was lost?

John S. Gray is clearly one of the searchers after fact rather than the mythographers, or the cultural historians. In his previous Custer book, “Centennial Campaign” (1976), he traced the political background behind the war that President Grant, along with generals Sherman and Sheridan, declared against the Sioux and allied tribes who were resisting the (illegal) immigration of gold miners into the Black Hills. But in “Centennial Campaign” he stopped short of dealing with the ambiguities and intricacies of the Battle of Little Bighorn itself.

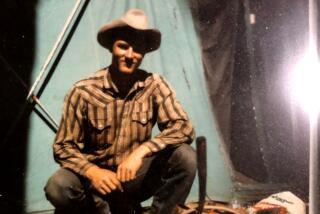

In “Custer’s Last Campaign,” Gray returns to the story of Little Bighorn and the time and space in which it occurred. Intriguingly, in what may strike some as an over-scrupulous adherence to mere facts, he also takes Custer’s personality (but not his decisions) out of the question. Gray’s human focus is instead Custer’s chief scout, Mitch Boyer, son of a French father and a Sioux mother, married to a Crow woman and adopted into the tribe. Boyer was called the best guide in the West, second only to his mentor, Jim Bridger. As interpreter, trapper, occasional courier, mailman, blacksmith, carpenter, he summarizes a life on the frontier that chroniclers of Custer’s glory usually leave out and to which Gray devotes the first half of his book.

In the second half, Gray explores the possible coherence in the fabric of misinterpretations, overlooked circumstances and faulty memories (as well as efforts by various Army personnel to cover their own butts) that followed the Army’s defeat at Little Bighorn. In detailed time-motion charts, he brings every documentable moment of Custer’s march and battle, including scouting forays and even individual gestures, into a pattern. The result is a “surround” for Custer’s own actions that reconciles anomalous and confused testimonies, and gives some solid basis for speculation on those events for which there remained no living or credible witness.

You won’t therefore find out much from “Custer’s Last Campaign” about the Fetterman “massacre” (an earlier Indian victory). Nor does Gray speculate about his attitude toward Capt. Frederick Benteen and Maj. Marcus Reno, whose delay in responding to Custer’s orders may have sealed his doom. No, Gray essentially argues that Custer was doing what he was ordered to do by Gen. Terry, and that his decisions were those of an experienced officer.

The result is fascinating for anyone who has more than dipped into the vast literature of the West, the Indian wars and Custer. Gray challenges many time-honored beliefs about the battle. Perhaps most significantly, he brings in as much as possible the testimony of the Indian witnesses, especially that of the young scout Curley, which generations of historians have dismissed for contradictions that Gray convincingly demonstrates were caused not by Curley but by the assumptions made by his questioners.

Among Gray’s bolder (but well-argued) speculations are that the advance down Medicine Tail Coulee was not in the line of march but a feint to pull Indians away from Reno’s men; that Custer reconnoitered from the top of Weir Peak and then took most of the men down Cedar Coulee; that what appears to be a counterclockwise movement in the final battlefield suggests that there may have been actually two last stands: Custer’s and a rear-guard action under the command of Lt. Calhoun.

If that paragraph made any sense to you, you’ll want to read this book. If not, put it aside for now until you’ve finished Dee Brown’s “Bury My Heart at Wounded Knee,” Richard Slotkin’s “The Fatal Environment” and Gray’s own “Centennial Campaign.”

Gray’s book is a fascinating contribution to an argument that has been going on ever since the last gun was fired and the last arrow fell to earth at Little Bighorn. The contrasts in his book--the personal history of the “half-breed” Mitch Boyer and the analytic precision of the time-motion studies of Custer’s march--restates the basic components of what still attracts the imagination to Little Bighorn.

For Gray, Boyer is an emblem of the human reality ignored in the polar opposition of white and Indian that has falsified and misshaped American history. Unfortunately, his somewhat blunt prose never quite succeeds in bringing Boyer to life. But the urge to understand Little Bighorn, and through it something about America, seems undying.

Within this decade, as reported in “Archaeological Perspectives on the Battle of Little Bighorn” (1989) and commented on by Gray, researchers working on the battlefield found an intact fragment of the left side of a face from eye socket to teeth and upper jaw. It fits perfectly over the same area in one of the only known photographs of Mitch Boyer.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.