MOVIE REVIEW : Tornatore’s ‘Everybody’s Fine’ a Mixed Achievement

- Share via

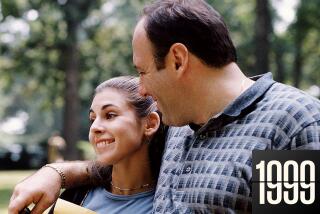

In “Cinema Paradiso,” Giuseppe Tornatore tried to thread our universal love of movies into the life and death of one small provincial Sicilian cinema. In his latest film, “Everybody’s Fine” (“Stanno Tutti Bene”) at the Westside Pavilion, he tries to compress modern Italy’s social illusions into one old man’s absurd, poignant quest to reunite his family. It’s a mixed achievement--overreaching, stylized--but touching.

The silly, determined old man is played by Marcello Mastroianni, the archetypal leading actor of the postwar Italian cinema, the star of “La Dolce Vita,” “8 1/2,” “La Notte” “The Organizer,” “The Stranger,” “A Special Day” and dozens of others. In his youth, Mastroianni was a symbol of romantic alienation and ennui. In his 60s, he retains a matinee idol’s profile and bearing.

But here, he plays an endearing old fool. Glasses weirdly magnify his eyes and a ridiculous, slightly askew mustache suggests a dudish walrus. Mastroianni’s Matteo is out of place, an eternally unwelcome guest, a Sicilian villager who decides to visit his children, scattered in Naples, Rome, Florence, Milan and Turin because, apparently, they have no time to visit him.

The children may all, to some degree, have settled for mediocrity. And, because he’s always pushed them too hard, they will seek to hide it from him. The movie extra and unwed mother pretends she’s an opera diva; the Communist Party gofer pretends to be a government minister. The most brilliant of the family, the Neopolitan academic, seems to have disappeared entirely: where, we will only learn at the end.

Yet Matteo, a romantic who named them all for operatic heroes and heroines, refuses to see this--or seems not to see it. He keeps recalling insistently, a moment when he, his children, his off-screen wife were all together on the beach--a dreamlike incident or fantasy that, for a harrowing reason revealed in the movie’s most spectacular image, embedded itself in his memory.

The search here is a sentimental journey, of course. But what constitutes sentimentality; what constitutes honest emotion? In “Everybody’s Fine” Tornatore seems trapped between the two.

It’s a much more ambitious film than its predecessor, more complex geographically and emotionally. Tornatore takes us on a tour of Italy that at times seems drenched with pathos, at times a vivid satire of contemporary malaise. Tornatore tries more tones and effects than he can reasonably handle, but there’s something exhilarating in the attempt.

When a director makes a huge international hit with an early work--as Tornatore did with his second feature, “Cinema Paradiso”--his next film may suffer the equivalent of a sophomore jinx with audiences and critics. But Tornatore is still only in his mid-30s, and the divided responses he evokes may reflect a division in his talent.

Right now, he seems stronger visually than he is dramatically, better at communicating through pictures than through people.

Tornatore likes big, sweeping effects, such as the bravura seaside camera movements that open and close “Everything’s Fine.” He’s still movie-obsessed: Numerous images recall Fellini or De Sica and there are five Sicilian children because there were five in the family of Visconti’s 1960 “Rocco and His Brothers.” And he is a stronger director than writer, better at broad strokes than the minutiae of behavior.

But, though he wrote “Paradiso” alone, he used a collaborator on “Everybody’s Fine.” And his co-writer is one of the great names of Italian cinema, Tonino Guerra, Antonioni’s principal partner from “L’Avventura” on, and a favorite scenarist for Francesco Rosi, the Tavianis, Fellini, De Sica.

Guerra usually works for directors who don’t overuse dialogue. Here, “Everybody’s Fine’s” central character is a lonely, verbose old man who continually strikes up chats with strangers. So Guerra’s major contribution may be that sense of alienation, disparateness, vulnerability in the city scenes. As Matteo’s travel continues, we can feel the weight of disappointment, even of irony, eroding his strength, feel how egotism both shields and entraps him.

There’s something shallow in parts of “Everybody’s Fine” (Times-rated Mature, for partial nudity)--but it’s a movie of feeling, social engagement and visual beauty. “Everybody’s Fine” is a quest film that tries to draw together, symbolically, all Italy into its single-family story, crystallize false national hopes and dreams within the old man’s comic/pathetic breast. If it doesn’t get everything it’s after--it’s a movie that was probably imagined as a masterpiece--it’s not that important. Few films, after all, could.

‘Everybody’s Fine’

(‘Stanno Tutti Bene’)

Marcello Mastroianni: Matteo Scuro

Michele Morgan: Woman on Train

Marino Cenna: Canio

Roberto Nobile: Guglielmo

A Miramax Films release. Director Giuseppe Tornatore. Producer Angelo Rizzoli. Screenplay Tornatore, Tonino Guerra. Cinematographer Blasco Giurato. Editor Mario Morra. Costumes Beatrice Bordoni. Music Ennio Morricone. Art director Andrea Crisanti. Set designer Nello Giorgetti. Running time: 1 hour, 52 minutes.

Times-rated: Mature (language, sexual discussions, mature themes).

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.