COMMENTARY : A Day Without Art

- Share via

A wise person once said that when a loved one dies, it’s a tragedy; when a stranger dies, it’s a statistic.

Today is World AIDS Day, a grimly necessary occasion designed by the World Health Organization for hard reflection on the mounting global toll of lives extinguished by the disease.

For the past three years, the art world has called attention to this event with a varied program called “A Day Without Art.” Organized by a collective called Visual AIDS, “A Day Without Art” has attempted to transform the ever-growing pile of statistics about the epidemic into the flesh and blood of a human tragedy.

The program takes almost as many forms as there are participants: 3,000 diverse international institutions, including 100 in Los Angeles, from the largest museums to the smallest artist-run organizations. Still, its mission is straightforward. Establishing a day without art--without, that is, the creative product of human hearts and minds--means to illustrate the magnitude of human loss as a result of AIDS.

And what is that toll? According to the World Health Organization, nearly 11 million people so far have been infected with HIV, the virus believed to cause the collapse of the human body’s immune system, making it vulnerable to fatal attack. Of those, 1.5 million people already have developed AIDS, which is the late stage of infection. Of all people with AIDS, one in three is a child.

By the end of the century, just nine years from now, the World Health Organization predicts that 30 million to 40 million people will have become infected with HIV. Conservatively speaking, that number translates into about one person with HIV for every 150 men, women and children currently alive on the planet.

The statistics are cold. In its ongoing effort to keep a human face on the disease, the organizers of “A Day Without Art” have begun to compile “The Witness Project,” a census of those in the arts who have died. So far, the list includes more than 1,000 names.

Last year, people in the visual arts were joined in “A Day Without Art” by volunteers from the dance, design, fashion, film, literary, music, performance, television and theater communities. All will join forces again this year. Once more, exhibition spaces will be closed, shrouds will be hung over paintings and sculptures, lights on theater marquees and skyscrapers will be dimmed, commemorative red ribbons will be pinned to lapels. Bravo, the cable television channel, will simulcast “A Moment Without Television” on 26 cable and satellite services at 11 p.m.

In some places, a recorded sound installation will be played throughout the day. Called “Every 10 Minutes,” the subliminal recording of a sonorous church bell rings at an interval matching the current rate of deaths from AIDS in the United States. Ask not for whom it tolls.

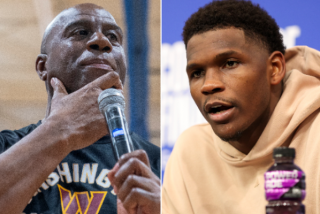

Today, more Americans than ever know the answer. One very big, very obvious difference can be cited between World AIDS Day 1991 and World AIDS Day 1990, 1989 or 1988. His name is Earvin (Magic) Johnson. For hundreds of thousands of people, Johnson transformed--literally in the blink of an eye--a statistical stranger into the tragic loved one. In our culture, it’s doubtful an artist could have done that.

Johnson’s announcement of his infection with HIV hardly obviates the need for “A Day Without Art.” For as the number of people conscious of the epidemic has expanded exponentially, so has the confusion surrounding the disease escalated. Battles long since waged by those in the trenches of AIDS are being fought anew.

Consider: Did Magic Johnson contract HIV because he is “immoral”?

A bizarre question, it’s true. Especially at this late date, nearly 11 years into the global epidemic. But it’s a question that has not just been asked, it’s been answered by some in the affirmative.

Within minutes of Johnson’s press conference last month wherein he announced his HIV status and his retirement from professional sports, Lakers announcer Chick Hearn, audibly shaken, raised the morality theme--ostensibly to squash it, although it didn’t come out that way.

In a radio interview, Hearn wanted to assure everyone that he was certain Johnson had gotten HIV “from a girl,” and thus not, by process of elimination, through illegal use of drugs or from sexual intercourse with another man.

There are three principal ways that the virus is transmitted:

* through unprotected sexual intercourse with an infected partner;

* through infected blood or blood products;

* from an infected mother to her baby before, during or shortly after birth.

Apparently, Hearn thinks particular channels of transmission should also be distinguished from one another by a “moral” dimension.

Dave Anderson, sports columnist for the New York Times, seems to agree. In a recent column he assailed the basketball superstar for promiscuity, declaring: “Magic Johnson is hardly a model or ideal to anyone with a sense of sexual morality.” The fact that Johnson’s heroism lies in a celebrity’s courageous but unprecedented candor about his affliction with HIV and in nothing else took a back seat to Anderson’s high-minded finger-pointing.

And it was fairly blown out of the water by Cal Thomas, a syndicated conservative commentator in Washington. Johnson’s infection, Thomas portentously announced in his column, is nothing less than a consequence of having violated “the moral laws of the universe.”

The insistent effort by some to cast AIDS as principally a moral issue, rather than a health issue, has been among the most pernicious obstacles in the struggle for prevention and treatment.

At one extreme is the “wrath of God” rhetoric, which argues that AIDS is retribution for sinfulness--an explanation worthy of the Dark Ages, but touted nonetheless from assorted modern pulpits.

At the other extreme is Kimberly Bergalis, the young woman in Florida believed to have contracted HIV from improperly sterilized tools used by her infected dentist. “I didn’t do anything wrong,” she repeatedly insisted to press and politicians, as if a virus should somehow have known the difference and at least played fair.

The implication that some ways of contracting this, or any, disease are vice laden--and thus “deserved”--has been around since the start. Would the corollary follow that there must, by definition, also be virtuous ways to become infected?

From religious leaders and elected officials to pundits and armchair quarterbacks, plenty of people have been quick to cast the first stone. But, transforming AIDS from a health issue to a moral issue seeks to divide people with AIDS into the innocent and the guilty--into “us” and “them.” Those who insist on it merely succumb to superstition.

Why? For the same reason any group has ever wanted to partition and segregate others: In the face of our powerlessness to cure the disease, we divide and--supposedly--conquer.

What a pathetic way to organize a moral universe. Fortunately, “A Day Without Art” has been organized by a diverse group of art professionals who understand that the disease is a matter of public health, not morality, and who recognize that the social context within which AIDS has emerged will continue to try to distract from that fact.

The great thing about “A Day Without Art” is that it keeps our moral compass pointed exactly where it should be: On the horrific sense of loss, which is the final truth of AIDS that touches everyone.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.