Always on the Stump : Even When He’s Not on the Ballot, Jesse Jackson Keeps His Rivals Hopping

- Share via

JACKSON, Miss. — Jesse Jackson, perpetually late, is once again behind schedule. His black limousine has already pulled away from the curb outside Jim Hill High School here when a passenger points out the schoolgirl. She is inconsolable, sobbing loudly over her missed opportunity to meet the erstwhile Democratic presidential candidate.

“Stop,” Jackson commands the driver. “Where is she?”

Jackson is due that very moment at City Hall, having overstayed a school assembly where he pleaded with students to stay away from drugs and to register as voters. But now, as he hurries off to lecture city officials, a potential voter is being left in the lurch. Jackson steps out the door as the driver hits the brakes.

“Come here, baby,” he says.

She cannot believe her luck, gleefully squealing as she races to Jackson’s bear-hug embrace. “I love you,” he tells her as he sinks back into the limo’s rear seat. “Now stay in school. Register to vote. Make me and your parents proud of you.”

Rep. Mike Espy, the black Mississippi Democrat who had been nearly trampled by the crowd rushing past him for Jackson’s autograph, looks on with apparent envy and contempt.

“I think you just earned her vote in the presidential election,” he notes dryly. But this is 1992. Unlike 1988, when 7 million people voted for Jackson, the girl’s ballot would be of no benefit to him this election cycle.

Espy smiles; he has scored a point at the expense of Jackson’s obvious--and now politically worthless--popularity.

“You never can tell, Mike,” Jackson retorts without missing a beat. “That young woman will vote someday, and she will remember those who came to visit her and how they took time away from their schedules to let her know somebody loves and cares about her. She will remember me.”

Then Jackson settles the score:

“You know, Mike, I’m only doing what every black elected official should be doing. I’m building a bigger base than what currently exists. I can’t understand why other politicians aren’t visiting a high school a week and registering students as voters.”

Jesse Jackson isn’t running for President this year. Or is he?

Four years after finishing second to Massachusetts Gov. Michael S. Dukakis in the race for the Democratic nomination, Jackson--the party’s troublemaker--is still on the hustings.

For 1996? What does Jesse want? Respect? What makes Jesse run? Why is he out there?

Jackson bristles at these questions, staples from skeptical journalists and political insiders of his former presidential runs. Despite the frequency of their delivery, Jackson has never satisfied his critics with an acceptable answer.

“Those questions are insulting, and they are racist,” he says. “They imply that a black can’t be President, that I shouldn’t dare to run. They overlook the fact that whatever I’m doing touches people--not just black people, but whites too.

“Family farmers and workers, they all understand my message. They came and heard what I had to say. They didn’t ask, ‘What does Jesse want?’ They weren’t trying to make me go away and leave them alone. They were happy I showed up to speak out for them.”

This election year is different. Jackson is not an official candidate, but he’s still stepping into the limelight. And the question returns: Why is Jackson out there, carrying his stock populist message to black college students one day, Baptist church members the next morning, white law professors at a clubby cocktail party and a basketball stadium packed with cheering white college students?

What makes Jesse campaign?

“We are running,” he says in casual conversation during a recent three-day voter registration drive that carried him in turn to Jackson; Fayetteville, Ark., and Durham and Manchester, N.H. “We’re not running for the (presidential) nomination. We’re running to change the nation.”

Jackson’s vehicle for change is the National Rainbow Coalition, the political extension of himself created during the summer of 1983 when he discovered that nobody--particularly black elected officials--was doing much to increase voter registration among the poor and minorities and working class across the country. His successes among this broad swath of disillusioned Democrats paved the way for his first presidential run in 1984 and were repeated in 1988.

Today, the Rainbow--as staffers call their organization--has as its prime directive passage of legislation to transform the District of Columbia into New Columbia, the nation’s 51st state. As the district’s elected “shadow senator,” Jackson most likely would become a fully empowered U.S. senator, with a portfolio to travel the globe and address his own agenda. And, under this scenario, the Rainbow would be one step closer to being a fully recognized political party.

Though he will not describe it as such, this is Jackson’s dream. Nothing would please him more than to see his Rainbow, already a populist movement growing within the Democratic Party, spanning the nation as an instrument of social and political change.

Jackson’s proudest political moment of the season transpired in January, when each of the announced Democratic contenders genuflected before the Rainbow at a daylong forum. It was a moment of triumph for him: The Democratic insiders, who discounted his previous campaigns, were making the symbolic pilgrimage to solicit votes from his band of political outcasts.

Each of the candidates arrived and, in typical Jacksonian style, they were asked on the spot to campaign in an inner-city neighborhood, at a homeless shelter, bankrupt family farm or some other “point of challenge” with--you guessed it--Jesse Louis Jackson. All agreed.

“Today is a testament to our work,” Jackson told the 500 or so who gathered at a Washington hotel ballroom in January to hear the candidates pledge allegiance to the coalition’s “Ten Commitments” or risk not securing his blessing on their campaign. “Every major candidate for the nomination of the Democratic Party is here to seek your support.”

Surely it didn’t escape Jackson’s notice that Arkansas Gov. Bill Clinton--who apparently forgot or failed to heed his campaign promise before the Rainbow faithful--rushed last week to brand him a turncoat when told, erroneously, that Jackson was supporting Sen. Tom Harkin for the Democratic presidential nomination.

“For him to do this to me . . . is an act of absolute dishonor,” Clinton fumed before an open microphone and television cameras. “Everything he has bragged about--he has gushed to me about trust and trust and trust, and it’s a back-stabbing thing to do.”

In reality, Jackson is doing only what he promised. The first of his “Point of Challenge” campaign appearances takes place today, when Harkin travels with him to South Carolina for whistle-stops before that state’s primary election.

But Clinton’s intemperate comments reveal the level of distrust between the mainstream Democrats and outsider Jackson, pouring fuel on Jackson’s belief that party leaders don’t trust him or his emotional brand of politics.

“A bird with only one wing can’t fly,” Jackson is fond of saying. Implicit in his statement is the belief that Democrats--particularly Clinton, who as head of the Democratic Leadership Council succeeded in moving the party away from liberal causes to attract white Southern voters--are shifting the party’s focus away from the populist causes dear to Jackson.

“A few years ago, some (Democrats) organized with explicit purpose of distancing the party from its base--from African-Americans, Hispanics, women, labor, peace activists,” he told delegates to the Rainbow’s presidential forum. “They wanted to play push-off politics--to make political profit by stiff-arming the base of the party to appeal to the so-called independent voter.”

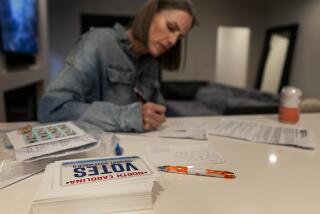

So Jackson is on the campaign trail. His goal is a 25% increase in voter registration in the nation’s 50 largest cities. That translates to some 10 million new voters, who are likely to be inner-city blacks, working poor and others uplifted by his promise of “expanding the Democratic Party.”

As their leader, Jackson--candidate or not--will hold their proxy until the Democrats realize the White House will forever remain beyond the party’s grasp without grass-roots support. Then, says Jackson, the Democrats will come to him--and on his terms.

This will be his retribution, a settling of the score for injuries inflicted by the Democratic Party mainstream.

The child of an unwed teen-age mother, Jackson has carried the demons of his childhood to near the top of America’s political process. He is still haunted.

He still seeks the respect of that political system, which seems intent on having nothing to do with him. That system includes the Establishment media that consistently underestimate him and the political insiders who want to use his talents, then discard the man.

“The media missed the story of my campaign in 1988,” Jackson says, just before a speech at the University of Arkansas. At this moment, he is fighting off the onslaught of a feverish flu and his defenses are lowered, but he’s not too weak to make his plea for understanding. “They missed the story of a black man drawing crowds (of whites) like this. These people want to hear and embrace what we have to say.

“If the press would only cover this,” he sighs, “it would send a signal all across America that it is all right to come out. Nothing is going to happen to them if they hear what we have to say. Nobody is going to eat them.”

Jackson says he will continue to campaign for the eventual Democratic nominee this year even as the party discounts his influence.

“They leave us out of the equation,” he says, noting that earlier insider speculation on additional entrants into the Democratic race had consistently avoided his name. “That’s as racist a jab at me as if it were a shot from a gun. They know I beat (Tennessee Sen. Albert) Gore and (Missouri Rep. Richard A.) Gephardt. Got more votes than either of them. But they don’t mention me. It’s like I don’t exist and the people who are with me don’t exist.”

Then he adds, “I know how to make myself more acceptable, but I have too much integrity to do that.”

Furthermore, Jackson believes, if he does what he’s planning well enough, the party will have little choice but to become more accepting of him.

“What I am doing now--registering people to vote and trying to get statehood for the District (of Columbia) and trying to have same-day, on-site registration on the ballot--are things I couldn’t do if I were running for President this year,” he says. “I’m more effective doing what I’m doing for the moment.

“After this, 1996, who knows?” he adds. “I think the party will recognize what’s missing--there’s no excitement generated by those other guys--if I sit this one out. There are people out there in search of a leader, and they know what’s genuine from fake every time.”

This is the voice of the authentic Jesse Jackson, which reveals itself in the relatively rare quiet moments between public performances. Those moments come in the confines of a university locker room before a speech, or in the cabin of a jet cruising 30,000 feet above America, or in a spontaneous phone call at any time of the day or night.

“We are afflicted with a double standard that forces us to work twice as hard,” Jackson says, speaking, as is his habit, in the royal plural. “If we work twice as hard, we develop twice as many muscles. Once we develop those extra muscles, nobody can take them away from you.”

Exercise time comes in front of some 14,000 people in Barnhill Arena at the University of Arkansas, where Jackson persuades about 1,000 unregistered students to sign up for the state’s Super Tuesday primary on March 10.

“If this happens all across the country,” he tells them, “you’ll have (presidential) candidates coming here and talking about the ‘student class’ instead of the ‘middle class.’ Tonight, I want you to change your status within the political process from ‘those students’ to ‘my distinguished constituents.’ ”

The bleachers empty at his feet. Potential Jackson voters-- 1996?-- rush to put their names on the voter rolls.

The exercise continues the next morning at the University of New Hampshire, where hundreds of students march to the Durham Courthouse to beat a noon deadline to register for the state’s primary.

“When young America comes alive,” he tells a cheering crowd of mostly white students, “we make the whole world better.”

“Run, Jesse, run!” the students chant back.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.