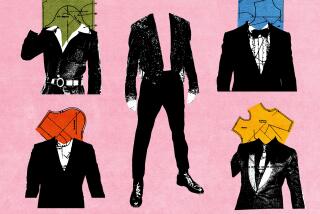

Whatever Happened to the Gray Suit?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — The men were ink. The men were night sky. They were indigo and black azure and marine.

It was as though the House chamber had become flooded by deep water. A blue Cabinet. A blue Senate. A blue House. A tank at Sea World. Old men and the sea. Shirt collars were bobbing like whitecaps along the surface.

It was blue, blue, blue as far as President Bush’s eyes could see as he delivered the State of the Union address in his own blue shirt and blue tie and dark blue suit the color of Superman’s hair. Vice President Dan Quayle, trapped in his own blue-ness, was sitting behind the President.

Darkness is key. Dark blueness is all. The Blue Suit endureth in Washington, a monument to sobriety and every politician’s right to pursue the electoral majority and look OK on television.

This dates, as does everything else in very modern history, it seems, to that great benchmark of American politics: the first Kennedy-Nixon debate in 1960.

Richard Nixon--pale and sweating, no makeup hiding his 24-hour 5 o’clock shadow, his shirt collar loose on his neck--wore a light gray suit. Light gray. It made Nixon seem insubstantial and meek. On black and white television, he and the backdrop were the same color, a combination of wet cement and cardboard. He became invisible but for a pair of rubbery hands wiping the sweat on his ashen face with a white hankie.

John Kennedy’s handkerchief stayed in his pocket. He had a slight tan. His suit was deep and dark and blue.

Nixon lost the debate. Since the Civil War, the gray suits have been losing. Television emphasizes the phenomenon: Under C-Span’s harsh lights, gray can read--no matter how dark the charcoal--like brown or, God forbid, an odd loden green.

And the point in politics is not to look green or sick or pale or powerless or the color of dirt. The point is to look strong, solid, serious, immaculate and impermeable. Black is for priests, waiters, Supreme Court justices and funerals. Blue is for admirals, police officers, our beloved elected officials and weddings.

Demonstrating flair--or looking particularly attractive to women--is not the purpose of the politician’s suit. It’s not the intention of blue-suitedness in general. The blue suit is not sexless, just beyond sex.

It’s a stable icon, the compromise between toga and breastplate. It’s the garb of a leader--not an individual, but a type, a person engaged in negotiations, trade, business, governing.

Smothered tastefully in blue--the suit and tie combo--one terribly wrong thing becomes OK, such as: the pleated vamp on a shoe, the ankle socks that show the calves, the trousers without cuffs, the too-narrow belt, the Pierre Cardin buckle, the clip-on suspenders, the monogram on a shirt cuff or one that’s too big on the pocket, the shirt collar with on-seam stitching, the shiny tie, the jacket with false buttonholes on the sleeve, the jacket with patch pockets, the jacket with a scalloped Western yoke, the hairpiece.

Forgiven. Forgiven if worn with dark blue.

Ronald Reagan was the exception who proved something: If you have nice shoulders and a good tailor, you can wear brown suits and get elected.

He wore the wildest--and therefore the worst--suits in American political history, most of them looking 30 years old, with roped shoulders and ventless jackets, made of something like the upholstery off an old Studebaker, and he won and won and won. This is why: Bad taste is American.

Aristocratic “furnishings,” if too snooty, are not American. And they can be far more dangerous to a politician than simple bad taste. A blue suit itself takes one perilously close to an upper-crust look, so caution must be exercised. The white linen handkerchief folded with perfect points, for example, can be deadly.

“You can’t expect to see a super-well-made, too-good-looking suit on a presidential candidate,” says one campaign trail veteran. “It’s got to look off-the-rack.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.