Search for Jane Doe Sidetracked to Find a Long-Buried Body

- Share via

Sheriff’s Detective Sam Bove walked the rural town of Jamul last summer in search of Jane Doe and ended up on the path of Vickie Eddington.

Recently coaxed out of retirement to join the Metropolitan Homicide Task Force, Bove was part of a team trying to solve a string of prostitute and transient murders. Scouring the streets of Jamul, 20 miles east of San Diego, Bove was trying to identify the remains of a woman found along California 94 nearby.

An evidence specialist with the Sheriff’s Department since 1963, Bove came across a business owner in the town who was more interested in the disappearance of 29-year-old Vickie Eddington.

That spark of interest led authorities to take the case seriously 4 1/2 years after it began. Prosecutors explained for the first time Wednesday, however, why it took so long to sort through evidence they had already collected but never examined for obvious clues.

The Eddington case first caused a stir in Jamul after the morning of July 31, 1987, when Vickie’s maroon Volvo station wagon was found abandoned 4 miles from her home, the tire flattened and no spare available.

Her husband, Leonard, had filed a missing-persons report that day and said his wife, from whom he was separated, was supposed to go to a nursing job in La Mesa the night before.

Eddington’s relatives and neighbors recalled his peculiar behavior in the days after she disappeared. He appeared so nervous to a sheriff’s deputy who took the missing-persons report that the officer turned the matter over to the homicide department.

Perhaps even more strangely, he used a tractor to move dirt into a ravine on several occasions after the disappearance. And, when Vickie’s family visited his home right after her disappearance, he kept them from wandering onto certain portions of the property and eventually ordered them to leave.

Now, in the summer of 1991, Bove vaguely recalled the case from 1987 and related the details to Richard Lewis, a deputy district attorney who was in charge of the task force.

Lewis ordered a file on the investigation from the San Diego County Sheriff’s Department. Detective Tom Streed, well known to the task force, had been handling the case.

Streed was a task force member in 1988 and 1989 who says he was forced into retirement over a separate matter involving the task force. He eventually filed identical $12-million claims against the city and the county for what he says was a smear to his reputation. He had been with the Sheriff’s Department for 23 years.

His file on Eddington contained 28 cassette tapes of interviews with principals in the case, along with Streed’s handwritten notes, telephone messages and the original missing-persons report filed with a sheriff’s deputy by Leonard Eddington.

Nothing was summarized in written form. No transcripts were available.

The bundle was handed over to Detective Dennis Brugos, who had joined the task force in late 1990. With little more than what Streed had compiled four years before, Brugos obtained a search warrant last December that allowed investigators to dig behind the Eddington property.

Task force investigators flew over the property in a helicopter late last year and noticed that the natural flow of the ravine had been blocked.

“Anyone who is familiar with how the land lies knows that you do not fill in a ravine with dirt,” Lewis said Wednesday. “It interrupts the flow of water on a property.”

Early the morning of Dec. 21, investigators began digging. They found a piece of fence secured by two wooden posts. Just below the gate, they found a green blanket and two homemade quilts that held the skeleton of Vickie Eddington. Then they arrested Leonard Eddington.

Prosecutors explained the chain of events that led to the discovery of Vickie Eddington during interviews outside court Wednesday, as Eddington’s preliminary hearing entered its second day.

During the hearing, which is scheduled to conclude this morning in San Diego Superior Court, Eddington’s mother, Marjorie, said she asked investigators digging last December why they waited so long.

“I said, ‘Why didn’t you do this 4 1/2 years ago and save us all this grief?’ ” she said. “It’s a terrible feeling not knowing where someone is.”

Investigators, including Lewis and prosecutor Jeff Dusek, are reluctant to criticize Streed’s efforts in solving Vickie Eddington’s murder.

Even Vickie Eddington’s parents say they have no misgivings about the investigation in that it ultimately resulted in the discovery of her remains and eased their minds.

But both Lewis and Dusek suggested that, if Streed had organized his information, he would have been able to obtain a search warrant. As it was, his scattered and disorganized file would not have justified the search warrant that led to the unearthing of Vickie’s body, they said.

Lewis said Streed had earlier tried to get a search warrant, but there is no record of his ever having done so.

“I don’t know what he had and at what time he had it or if he intellectually put it all together,” Lewis said. “I don’t know which way he was going. If it were me, if I had enough to put a guy away, I wouldn’t let him sit on the streets for four years.”

Streed could not be reached for comment, but Dusek speculated that Streed, like almost all homicide detectives, probably had too many murder cases before he joined the task force in September, 1988. When he did join the murder task force, he was looking specifically at cases that fit the prostitute-transient pattern, Dusek said.

In court this week, Eddington’s court-appointed attorney, Milly Durovic, has attacked the search warrants, saying the request for the warrants purposely omitted information that would have been beneficial to her client. Other pieces of information are outright misstatements of fact, she said in asking Superior Court Judge William D. Muddy that the search warrants be ruled invalid.

Mudd already ruled against Durovic when she asserted that the search warrants were flawed because they were signed by a judge who once worked as a deputy district attorney with some of the same prosecutors who are investigating the Eddington case.

On Wednesday, Durovic asked to allow Eddington’s mother, Marjorie, to testify because, at age 70, she is in such ill health that she might not be alive at trial. The request was granted.

In allowing Marjorie Eddington to speak about the events of her daughter-in-law’s disappearance, however, Durovic opened her to a tough cross-examination by Dusek.

“After the body was found on your son’s property, how soon was it that you asked your son how Vickie’s body got there?” Dusek asked.

“I could not get to see my son if I had a million dollars,” Marjorie Eddington said. “The police came and got him.”

“He got out of jail, didn’t he?”

“Right.”

“You helped post bail? How much money did you put up for his bail?”

“Twenty thousand dollars in cash and the equity in the property, and I don’t know how much that is.”

“Once he got out of jail, he was free to talk to you,” Dusek said. “Was it then your pleasure to ask him how Vickie’s body got buried on his property?”

“I didn’t feel like he had done it.”

“Why didn’t you ask him?”

“When you have confidence in a person, you don’t go around asking him about things,” Marjorie Eddington said.

“Well, I can tell you because I don’t think he put the body in there,” she said. “I don’t think the body was Vickie’s. It might have been Vickie’s, but I’m a farmer’s daughter, and I was all over that place out there the day she disappeared. There wasn’t any diggin’ or anything that amounted to any substance at all. And you don’t dig a hole (to) leave evidence.”

Marjorie Eddington said she doesn’t believe the body was Vickie’s, and her “mother’s instinct” tells her that her son had not committed murder.

Yet she conceded never really liking Vickie Eddington because “we weren’t that compatible. She was an independent gal and wanted to do her thing, and she didn’t care for my husband or I.”

Regardless of her personal feelings, Marjorie Eddington said, she went so far as to split costs for a private investigator with her son, Leonard, to find out what had happened to Vickie after she disappeared and to find out other details of Vickie’s life.

Both Marjorie Eddington and her daughter, Sylvia, who live on the same property next door to Leonard, testified that they never heard him move either his car or truck the night of Vickie’s disappearance. But they both acknowledged that they cannot see Leonard’s home from where they live because it is about a quarter of a mile away.

At the time Vickie disappeared, she was living in the couple’s two-story house on 4 acres, and Leonard lived in a trailer on the property. The night she left for work, her husband told police, he had been baby-sitting their three children.

A former clerk at a 7-Eleven convenience store in Jamul testified Wednesday that, the night of Vickie’s disappearance, a woman generally fitting her description entered the store about 10:30 p.m. Her car had broken down, she said, and she asked for change.

The prosecution has always alleged that Vickie Eddington never left home that night and was killed on the Eddington property. The clerk picked Vickie Eddington out of a photo lineup but acknowledged that he might have chosen her because a poster of her likeness sat in the window of the store for weeks after her disappearance.

The operator of a business that leases heavy equipment said Wednesday that Leonard Eddington rented a loader to clear brush from his property 2 1/2 months after his wife was reported missing, but that it was accompanied by an expert who operated the machine.

At least one neighbor has testified that she saw Eddington atop such a machine shortly after the disappearance, filling dirt and rocks into a ravine behind his home.

Prosecutor Dusek said Eddington had operated equipment on several occasions and suggested that clearing the brush in September was part of a scheme to convince neighbors that he was doing legitimate work on his property.

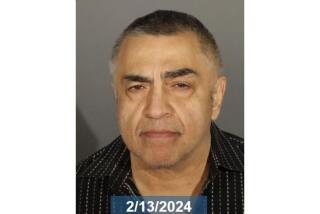

Leonard Eddington spent the second day of his hearing taking occasional notes and watching the witnesses. At one point, he glanced back in court at his new wife and his oldest son, Michael.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.