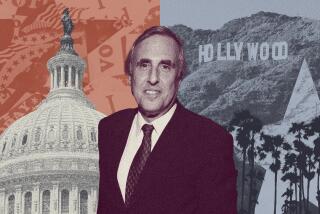

He’s on the Outside, but He’s Not Sorry : Careers: Ed Zschau may have passed up his best chance at a U.S. Senate seat to focus on a tiny computer device with big possibilities.

- Share via

SAN JOSE — In the scientific wonderland of Silicon Valley, where big things are being made smaller and smaller, Ed Zschau is holding a tiny sliver of metal tipped with a device that just might be a high-tech breakthrough.

It is so phenomenally small that its parts are measured by the width of an atom. But it is so big, Zschau says, that there is no way he could ignore it and instead make a second try at the U.S. Senate.

“We are doing things that no one has ever done before,” Zschau says at the modest, office-park headquarters of his new firm, Censtor Co. “I struggled with the decision, but it should have been obvious. We have a chance to change the (computer) industry.”

Six years ago, Zschau came almost from nowhere as an obscure Republican congressman in Silicon Valley to nearly upset three-term incumbent Sen. Alan Cranston. After a tumultuous statewide race that is still one of the most expensive Senate contests in U.S. history, Zschau lost by slightly more than 1% of the vote.

So naturally, when Cranston announced last year that he would not seek reelection, many Republicans thought Zschau would be a top prospect for wresting control of Cranston’s Senate seat from the Democrats.

“I think he would have a good lead right now,” predicts Sal Russo, a Republican political consultant in Sacramento. “It would not have been a done deal, but he certainly would have had a leg up.”

Zschau, who once built his own back yard enterprise into System Industries Inc., a prosperous Silicon Valley company, left a void in the Republican Senate primary when he exited the race in March, 1991. It was filled within hours by Rep. Tom Campbell (R-Palo Alto), the current holder of Zschau’s former seat in Congress and the heir to much of his predecessor’s political support.

Campbell is running in the June 2 Republican primary against conservative television commentator Bruce Herschensohn, who finished a close second to Zschau in the 1986 Senate primary, and Sonny Bono, the former Palm Springs mayor and ex-partner of actress-singer Cher.

From the sidelines, though, Zschau has daydreamed about the thrill of another campaign, reliving the heady experience of being in the company of the nation’s top leaders and opining about the vital issues of the day.

As it turns out, Zschau believes, this year’s unpredictable political landscape is probably even more fertile for his brand of politics than he thought when he decided not to run.

Unlike 1986, when he was hampered by trying to justify his moderate politics with then-President Ronald Reagan’s conservatism, this year’s debate has focused more on the economic issues that Zschau says he feels most comfortable discussing.

Zschau figures he could have run as an outsider with a can-do record in private enterprise--in some respects like Ross Perot in the presidential race.

“I had no idea the political environment would be like it is when I made my decision,” says Zschau, sitting in a barren meeting room with his white shirt sleeves rolled up and a corporate ID badge pinned to his chest. “Republican politics has clearly changed.”

Zschau says last week’s riots will force candidates to address the largely ignored problems of the inner city. Like U.S. Housing Secretary Jack Kemp, he says he favors a program of enterprise zones and investment incentives designed to give disadvantaged residents a financial stake in their community.

But Zschau’s recollections are not melancholy.

It may be that he has passed up his best opportunity to win a seat in the U.S. Senate. And while he is confident about the new frontier his company is exploring, he acknowledges that the tiny speck of machinery he is building might still fail.

But it is that uncommon acceptance of risk that created Silicon Valley, and even among those known for taking business gambles, Zschau has always been a standout. He claims his most important personal rule is so innate that it must be genetic--that is, never look back at what might have been.

“I could not have made a different decision” about his future even if the choice proves unsuccessful, he says. “Failure doesn’t stem from defeat; failure stems from not trying. If you never give up, you never fail.”

As it happened, the 1992 Senate campaign fell at a crucial time for Censtor.

When Zschau joined the company as chief executive officer in 1988, Censtor was preparing to manufacture conventional magnetic recording equipment. But within a few months, a scientist at the company developed a radical new component for retrieving computer memory.

Conventional computers store memory on a hard disk that spins rapidly. A recording head--almost like a phonograph needle--scans the disk while it hovers just off the surface.

Censtor’s patented invention is a recording head that actually rides on a disk surface, where it can more accurately read the data and, as a result, allow much more memory on the same size disk.

Censtor’s laboratories are straight out of a Space Age control room: There are microscopes with color television screens that can measure down to the size of a single atom and sealed, yellow-lit rooms where technicians walk around in what look like white space suits.

It was Zschau’s decision to change the company’s direction away from manufacturing and instead to focus on the potential for developing a new technology.

Now, after more than two years of research, Censtor recently sold three licenses to companies that will manufacture the new component. Within the next year, Censtor’s invention is expected to make its debut in a commercial product.

“The kind of enjoyment I like in all activities is creating something where there was nothing before,” Zschau says. “So this is a very enjoyable business for me. I can say, ‘There is something that would not be there if it was not for me.’ ”

Zschau is a Stanford University-trained physicist, but he also double-majored in philosophy. It’s a background that helps him bridge the seemingly incongruous worlds of science and politics.

And, he promises, one day he will make his second sojourn from the laboratory to the halls of government. He says, however, that he is uncertain what office he may seek. It may not be the U.S. Senate. And, he says, it may not even be elected office.

“I have to decide what I can do in public service to contribute,” he says. “If I run for something again, it will be to make a difference.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.