FIXATIONS : Master Copies : Vytautas Grakauskas’ Art Isn’t Original--but the Painter Is Devoted to Others’ Strokes of Genius

- Share via

SAN CLEMENTE — If one were to peer into Vytautas Grakauskas’ house without knowing the man, a couple of wrong conclusions might be reached, like maybe thinking he’s the world’s richest man, or at least its preeminent art thief. For covering his walls are Van Goghs, Gauguins, Cezannes, Monets and Matisses. There’s plenty more crowded into closets and stacked on racks made of PVC piping in his garage.

It is a bit of a giveaway that on an easel in his garage there’s a half-finished Van Gogh ocean scene.

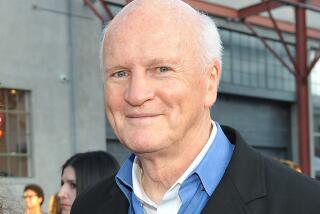

For the past five years the 66-year-old retired scientist has devoted himself to copying art masterpieces, and he’s not bad at all, particularly considering that he whips each one out in about 10 hours. Grakauskas has more than 250 completed, and isn’t really sure what to do with them, except make more.

“I may have to sell some of them eventually,” he muses, “mainly because my wife will throw me out of this house when there isn’t any more room.”

The large, amiable Lithuanian native speaks well-crafted English colored by a thick accent. He’s always loved and dabbled in painting, he said, but only took to it passionately after he retired from chemistry.

He has a computer-organized index of all his works, and even when tackling the emotional geyser of a Van Gogh canvas he takes a methodical, analytical approach to copying it, applying a cross-hairs grid to an art-book plate and using a coordinate system to sketch in the design on the bare canvas.

“That’s the tiring part. Van Gogh would do a painting in an hour, just slapping his paints all over the place. When he did it, he just did it, while I have to draw it out exactingly the way he did it or the painting will be ruined,” Grakauskas said.

None of which would be a problem if Grakauskas “just did it” himself, but he’s devoted to his copy work, which he admits is a glorified form of paint-by-the-numbers.

“Generally, copying is looked on as a somewhat secondary undertaking, but I find it fairly challenging and a way of learning,” he said. “And I came to the conclusion in reading the biographies of famous artists that you have to start quite early and really struggle to be great and original. I already put my energy into chemistry, and I don’t want to struggle right now. I think it’s too late for me to turn what I’ve learned into something unique.

“Also I think the field may already be full,” he said, pointing to his reproductions of two Van Goghs, which were indeed landscapes of fields. “He painted those from over the wall of his mental asylum. To do something unique is very difficult. And it is difficult to beat those things. So much of the art I see now is just some guy reshuffling things that have been done before, copies that aren’t called copies.”

A couple of years ago Grakauskas worked on his paintings for up to 10 hours a day, six days a week. Now he averages four hours a day. He works in his spotless three-car garage, where the light is good, and where the neighbor kids sometimes wander in and attempt to contribute some finger-painting technique to his brush strokes.

He’d wanted to paint since he was a child, but events like Russian and Nazi invasions, World War II and making his way in a new country interposed themselves. He grew up on a remote Lithuanian farm, which was taken from his family by the Communists.

“I was of draftable age, and the Russians wanted me to fight for Mother Russia, then the Germans came in and wanted me to fight for the Fatherland. Luckily I escaped all of them,” he said. After the war he came to the United States under the Displaced Persons Act, reaching Chicago with $1 in his pocket. With some help he got into school and emerged from the Illinois Institute of Technology with a doctorate in chemistry and a wife, Nijole, a fellow Lithuanian and chemist.

While he says Nijole is reasonably supportive of his romance with oil paints, “I wouldn’t be too surprised if she and others looked at me as a guy who is maybe getting a little on the senile side, and, ‘What’s he doing painting days upon days upon days, without any particular goal?’ I could see where I would be annoyed by a mate selecting such a hobby and sticking to it tightly. I think we have a good relationship, but nevertheless she might be a bit annoyed.”

Grakauskas has never displayed his work publicly and isn’t entirely sure what to make of it himself.

“I can’t really expect my friends to tell me, because I would find it hard to tell a friend if I didn’t like his art,” he said.

So last year he sent a photo of a copy he’d made of Gauguin’s “Fiesta” to art collector and all-around rich guy Walter H. Annenberg, who owns the original.

“I knew he was a busy, important man, but I was a daredevil and sent it with a letter asking him to evaluate it, honestly without giving me any bull, on a scale of one to 10. I never really expected him to answer.”

Two weeks later, Grakauskas got a card back, with a circled 9 and Annenberg’s signature in shaky script.

Some further indication of his copying abilities came when he gave a painting to a visiting Lithuanian relative, who wrote to tell them that while returning home through Germany, customs officials had taken the work for an original and slapped an appropriately high duty on it.

Grakauskas doesn’t place any great value on his paintings above the $15 or so in materials each one costs. He says there may only be 10 of the 250 that he’s entirely satisfied with, and when we talked he was on his third attempt at Van Gogh’s 1888 “Seascape at Saintes-Maries.”

Pointing to the art book reproduction he’s working from, he said, “Look at the intricacy of those waves, they’re just beyond the imagination. I’ve been working at it feverishly, and I still don’t know that I will get it right this time.”

After showing dozens of his copies, Grakauskas reluctantly pulled out a couple of his own paintings, which had been unceremoniously stuffed into a cardboard appliance box. Like his preference for the loud and colorful in his copies, the originals looked somewhat like forest fires, bold, free, and not at all expressive of the “rigid order” he says he brings to his reproductions.

A few moments earlier he’d argued, “If young people with full energy can’t create or find their way, who the heck am I to think I can?” Who indeed.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.