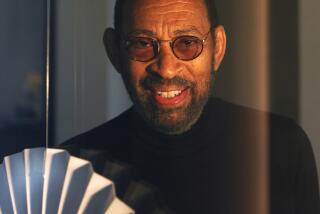

Eddie Brown, Rhythm Tap Master, Dies

- Share via

Eddie Brown, a master of rhythm tap improvisation who schooled a younger generation of dancers, died Monday at a convalescent hospital in Los Angeles. He was 74 and had been battling cancer.

Brown overcame poverty and alcoholism as well as decades of obscurity to win acclaim among tap-dancers as a dancer and teacher.

“He was one of the greatest exponents of rhythm tap,” said Rusty E. Frank, a tap historian who compiled an oral history of tap-dancing. “His rhythms were so musical and so complex that it was a thrill for people to watch and listen to him. He went far beyond what most tap-dancers even tried to grasp.”

Brown rarely performed routines. Instead, he mesmerized audiences with a no-nonsense, almost expressionless dancing style that featured genuine improvisation. When the band played, he would spontaneously weave delicately intricate, rhythmically diverse combinations.

“You can compare rhythm tap to jazz music,” Frank said. “As far as the resurgence of tap goes, he is one of the key figures on the West Coast. Since the 1970s, he has been available, willing and anxious to teach the next generation.

“In New York they had Honi Coles. In California, it was Eddie Brown. He kept rhythm tap alive.”

Some believe that Brown made his greatest contribution by passing on the rapid-fire, close-to-the-floor, musically complex style that is rhythm tap.

“He wasn’t ever afraid to give away any of his best steps because his best steps were constantly coming,” said Babs Yohai-Rifken, a San Francisco rhythm tapper and dance instructor.

Brown was born in Omaha, one of 14 children in a family that included musicians, singers and dancers. His most important early dance teacher was an uncle who would rap Brown’s ankles with a stick if he got steps wrong.

Brown also learned tap on the streets. In his day, teen-agers met on street corners to show off dance steps and learn from each other.

According to legend, famed tapper Bill (Bojangles) Robinson discovered the 16-year-old Brown during a tour in Omaha. Robinson asked Brown what number he planned to do.

“The same one that you do,” Brown said.

“And what music do you want?”

“The same music that you use,” came the answer.

Brown had memorized “Doin’ the New Lowdown,” one of his idol’s routines, by listening to the taps, scrapes, digs and shuffles on a scratchy recording. Then Brown went to a movie house to watch Robinson on film and match the sounds to the style.

The young dancer’s cheekiness was a risk because Robinson was reputed to brandish pistols at dancers who had stolen his steps.

And Brown had stolen them perfectly.

But instead of losing his temper, Robinson offered the boy a job.

Brown ran away to New York City when his parents would not let him join Robinson’s troupe. He eventually toured China with Robinson before World War II but left the troupe in the 1930s to become a solo performer, primarily in San Francisco.

After World War II, the market for tap dancers dried up and Brown taught himself to play the piano, getting by as a musician.

Brown said that despite those lean years he never considered giving up his dance. “I have this much time for mortal endeavors,” Brown told a friend once as he held two fingers about an inch apart. Then he extended his arms as wide as they would go. “This much is about my dancing.”

He emerged from the shadows in San Francisco in the mid-1970s, when he performed as the lead tap dancer in “Evolution of the Blues,” a music and dance variety show that traced the birth and development of blues music and featured noted black entertainers.

His performances inspired dancers to seek him out for lessons, and from that time, Brown’s class became a required stop for hundreds of students.

He moved to Los Angeles in 1982, where he continued teaching. Periodically, he participated in performance tours and dance conventions around the world, where he was typically a lead attraction.

Honors in recent years included two choreographer fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts and a star on San Francisco’s Walk of Fame. This year, local tappers organized two shows in his honor. The most recent, on July 26 at the Morgan-Wixson Theatre in Santa Monica, drew an overflow crowd.

Brown outlived his siblings, said Emelda Brown, a niece. A memorial is pending.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.