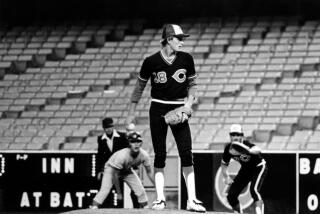

Proving Grounds : Schooler Wants to Show He Can Still Pitch

- Share via

ANAHEIM — One day Seattle Mariner Manager Lou Piniella is talking about a possible bullpen-stopper tandem of Mike Schooler and Norm Charlton.

The next day Schooler is on the waiver wire.

That’s life in baseball’s current economic climate, where the latest business trend, known as down-sizing, threatened to stamp out Schooler’s career in March.

Schooler, who played at Garden Grove High School, Golden West College and Cal State Fullerton, had made only three 1993 spring-training appearances when the Mariners released him after a 4 1/2-year career in Seattle.

Mariner executives said Schooler, who spent more than a month of the 1992 season on the disabled list because of a strained right biceps and spent the winter rehabilitating his pitching arm, had lost his arm strength.

They had a point. Schooler’s fastball, usually in the 90-m.p.h. range, seemed to have slipped into the slow lane, with readings in the mid-80s.

But Schooler, the Mariners’ all-time save leader with 98, felt his fat contract was more of a target than a questionable arm.

“After three outings, 95% of the guys in spring training don’t have their arm strength,” Schooler said. “It was all money. Every day in the Seattle papers, they were saying the team had to cut $2 million off its payroll. I was at $800,000, and they also cut Greg Briley, who was making $750,000.

“If they had this in mind, they shouldn’t have given me a one-year contract (through the 1993 season) or put me through a rehab program in the winter. It was a bad situation.”

It didn’t get worse, however. A week after his release, Schooler, who had 33 saves in 1989 (third in the American League) and 30 in 1990, signed with the Texas Rangers. He spent a little more than two months at triple-A Oklahoma City before the Rangers called him up Wednesday.

Schooler showed the American Assn. he still can pitch. After two rough April outings, in which he gave up 10 earned runs in 4 2/3 innings, Schooler went nine appearances, a span covering 13 innings, without giving up a run for Oklahoma City.

Now, the 6-foot-3, 220-pound right-hander wants to show the American League, especially the Mariners, that he still can pitch. The Rangers’ schedule provides a convenient stop in Seattle for a three-game series beginning Friday.

“My goal is not just to come back, it’s to contribute,” Schooler said Monday night before the Rangers’ game against the Angels in Anaheim Stadium. “I want to get into the groove I was in at Oklahoma City. I want to show these guys what I’m capable of doing.”

So far, he hasn’t been too convincing. Schooler gave up a home run to Minnesota’s Pedro Munoz during his 2 1/3 innings in a 6-5 loss Thursday, and he allowed a run and three hits in a third of an inning in Saturday’s 10-9 loss to the Cleveland Indians.

The Rangers had lost 12 of 18 games entering Monday night’s game, and Schooler hasn’t done a lot to shore up a shaky Texas bullpen, which has relied heavily--perhaps too heavily--on Tom Henke and Matt Whiteside.

But the organization is confident that will change.

“He threw well his first outing--his velocity was good and his slider was sharp,” Texas Manager Kevin Kennedy said. “After a day’s rest, he wasn’t as sharp on Saturday. Whether he needs more time between appearances, I’m not sure, but I did see major league stuff his first outing. I don’t want to judge a guy on two outings.”

Schooler, 30, hopes he can overcome this rocky start, just as he overcame the one in Oklahoma City.

“The first few weeks of the season I couldn’t string (together) back-to-back good outings,” Schooler said. “I just didn’t have my head in the game. I was still in a whirlwind, trying to figure out what the heck happened to me (in Seattle).

“Finally, it got to a point where I said, ‘Hey, my arm is fine, I’m throwing good, the only thing holding me down is my concentration on the field.’ Once I made that adjustment, I started pitching better.”

Schooler went 1-2 with a 5.93 earned-run average and five saves at Oklahoma City, but his ERA was skewed by two horrendous outings. He gave up five runs and six hits in 1 1/3 innings against Indianapolis April 13 and five runs and five hits in 3 1/3 innings against Louisville April 28.

Schooler earned a save or victory in each of his last four appearances, though, and he said his fastball was recently clocked in the 90-m.p.h. range, validating his belief that his oft-injured arm has returned to full strength.

Weakness in his right shoulder forced Schooler to miss the final month of the 1990 season, a partial dislocation of the shoulder joint sidelined him for the first half of the 1991 season, and a strained right biceps put him on the disabled list for five weeks in 1992. But none of the injuries were severe enough to warrant surgery.

“My arm is 100%--the only thing holding me back is bad pitch selection, not going after hitters,” Schooler said. “I’ve got to be more in tune to the mental aspect of pitching, taking it one batter at a time.

“I’m not going to light the radar guns up, but with the movement on my fastball and a slider to complement it, that’s plenty hard enough.”

Hard enough to stick in the major leagues? Schooler thinks so, but he’s also a realist. He’s going to hold onto that apartment in Oklahoma City awhile, just in case things don’t work out with the Rangers.

And if the Rangers decide Schooler doesn’t fit into their long-term plans, there are plenty of teams in need of bullpen help. While Schooler was playing in Oklahoma City, he couldn’t help but notice what little quality relief pitching the Angels have been getting.

“That would be too convenient because I have a house in Anaheim Hills and I grew up here,” Schooler said. “But in my heart, I hope I don’t have to look around at other teams. I know I can help someone, but I want to help this team. I really like this team.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.