PERSPECTIVE ON CIVIL RIGHTS : The True Concern Is Racial Justice

- Share via

Question: You played by the rules and you didn’t get the job as assistant attorney general for civil rights. Who would you suggest should get that job?

Answer: My concern is not about who is nominated, but how that person is supported and treated in their effort to vigorously enforce the civil rights laws. What concerns me is that the message of my nomination is not the particular treatment that I experienced, but the metaphor, the symbol, the significance of that treatment.

I am concerned that the way I was treated may suggest that no one is going to be able to enforce vigorously the civil rights laws because civil rights has become too controversial. We can’t talk about race; we can’t talk about racism. I was branded race-obsessed because I wanted to talk about what I see as the unfortunate but persistent racial divisions in this society. So I hope that the next person who is nominated is not only given a hearing, but that they are confirmed. But what I really hope and what I’m more concerned about is that they be given the support necessary to do the job, not just to get it.

Q: Does race matter in 1993?

A: I think if you look at the political landscape in this country that one of the most significant political cues is race. If you look at the election returns or the presidential elections in 1992, in 1988, in 1984--one of the first things that most political scientists notice is the way that people vote in “racial” blocs. It’s an unfortunate reality, but it is nevertheless a reality. George Bush was elected in 1988 by a majority of the white voters. He did not receive a majority of the black vote. Bill Clinton was elected with an overwhelming majority of black support. If we look at the way people are voting, that tells us that they see their interests in racial terms. And again, it’s unfortunate, but I think we have to start talking to people, particularly those people who still feel frustrated and alienated as a result of not having an opportunity to enter into an open conversation about their perspectives. If we talk to those people, I think we can discover, No. 1, that there are lots of points of common ground, and No. 2, that we don’t have to be so scared about talking. What we have to be scared about is silencing.

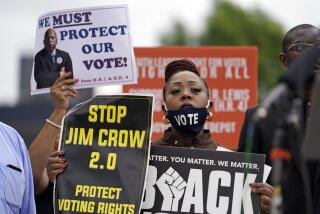

Q: Why is the Voting Rights Act so important 30 years after it was passed?

A: In part, you have to understand the history of the Voting Rights Act. The law was passed in 1965 because the Constitution, which had been amended after the Civil War, presumably to guarantee blacks the franchise, was never vigorously enforced. The 14th and 15th amendments of the Constitution were an effort to guarantee blacks an opportunity to vote. But when various black plaintiffs would bring lawsuits, and even if they were successful in bringing these lawsuits, the affected jurisdictions would simply change the rules. As soon as blacks won the opportunity, for example, to vote in the general election, then the white Democratic Party in Texas, for example, changed the rules to make sure blacks couldn’t vote in the Democratic primary, and all the key decisions were made within the party primary. The process of challenging those exclusionary rules took almost 25 years.

The Voting Rights Act as a result was passed with the idea and understanding that it wasn’t enough simply to declare that we are a free society, that we are a democracy, that everyone should register and vote. The Voting Rights Act was passed with the understanding that the law had to monitor beyond simply a rhetorical declaration the actions of some of these jurisdictions who were determined not to have blacks registering, then not to have blacks voting, then not to have blacks electing people to office. And now many jurisdictions in some of the areas where I’ve litigated do not want to have those blacks who’ve been elected to office exercising any real power or influence.

In Etowah County in Alabama, for example, as soon as the first black was elected to office, under a lawsuit, pursuant to a lawsuit filed under the Voting Rights Act, the white lawmakers changed the rules to seize power from that individual. In Texas, as soon as the first Latina was elected to the school board in a local county election, the white lawmakers changed the rules. Before she was elected, any one individual could put an item on the agenda. After she was elected, the rules changed so that you needed a second just to get an item on the agenda. She could not even get her issues talked about, much less voted on, because of this rule change.

Q: What does the Supreme Court decision on this year’s North Carolina case do to voting rights?

A: Well, there are two ways of looking at that decision. One way is to look at the decision very narrowly and to see that decision as an expression of concern about the efforts in some jurisdictions to remedy persistent racial exclusion by creating single-member districts that might perpetuate racial separation.

The other way to look at that decision, and what I fear is the more realistic way to look at that decision, is that the majority of the court--in an opinion joined by Justice Clarence Thomas--the majority of the court is telling us that the court is more worried about its commitment to a colorblind society than it is about remedying the reality of racially divided politics. The problem with that thesis, or that principle, in this particular case in North Carolina, is No. 1, the district was drawn to remedy a century of exclusion. No black had ever been elected to Congress (from North Carolina) in this century before the 1992 redistricting plan. No. 2, this was not a district that separated the races. This was the most integrated district in the state--it was 54% black and 46% white. Most people would call that a competitive district.

So this was not a district that was packed or stacked; this was a district that was created to integrate voters who had something in common. This was a district in which the major metropolitan areas in North Carolina were linked together to create the only urban district in the state.

Many people looking at this district on a map would admit that the shape of the district is odd and irregular. But my view is that you can’t measure the value of a district by looking at its shape. You have to assess its feel, and the way you determine how the district feels to the voters who live there is by asking whether the representative, in this case Melvin Watt, can function. Can he manage this district? Can he represent this district? Does this district represent a community of interests? And I think the answer to that, in this case, is yes.

What I find most disturbing about this court’s opinion is that it seems uninterested in any remedy. It is more interested in providing these five white voters in North Carolina an entirely new, unprecedented, constitutional right to challenge a district that didn’t deny them any political power or any individual right to vote. So in that sense, it’s unfortunate and misleading to call this district even a racial gerrymander because gerrymanders are the drawing of districts that arbitrarily allocate disproportionate power to one group or another. This district did not allocate disproportionate power to anyone. This district was drawn in response to the Voting Rights Act, in response to a Justice Department objection, to allocate power in a fair way for the first time.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.