Murder in Montana: Victims Included Rancher and Innocence : Crime: Wayne Stevenson’s death was as if Ben Cartwright had been slain. A man sought by California on murder charge is accused.

- Share via

HOBSON, Mont. — Wayne Stevenson didn’t have to check his cows every night. As one of Montana’s most prosperous ranchers, the nation’s biggest breeder of Black Angus cattle, he had hired hands for that.

But he also was a man who fussed over his cows as if they were children, especially in calving season. A breeched calf might have to be pulled out of its mother. A cow could steal another’s newborn calf. There’s no telling what might happen.

And so at 9 p.m. on March 27, Stevenson climbed into his mud-caked truck and drove 10 miles out to his calving shed, a dark and cavernous barn packed with pregnant cows.

It was just like any other night--until the ransom call at 11:41.

“I’ve got your husband and his red pickup, and I want $1 million in 24 hours,” a man told Stevenson’s wife, Marian.

Two days later, searchers dug Stevenson’s bullet-riddled body out of a manure pile in a lean-to near the calving shed. On March 31, a trusted ranch hand was charged with the crime.

Stevenson’s death was unsettling enough for the 226 people of Hobson, a speck on the map in central Montana.

But the shock reached far beyond Judith Basin County, which hadn’t had a murder since 1945. As more than 1,000 mourners poured into town for the funeral, Stevenson’s stature in the ranching world became clear.

In an age when the Old West image of rugged ranchers has been diluted by absentee landlords and agribusiness conglomerates, Wayne Stevenson was the real item: a cattleman’s cattleman who thrived on the harsh Montana range only to be betrayed while doing what he loved best--tending his herd.

It was as if Ben Cartwright had been murdered.

“He didn’t want money,” said his daughter, Valerie. “All he wanted was better cows.”

“Everybody went to him for advice on cattle,” said Tess Brady, an old friend. “If they needed a bull, he’d loan them a bull. If they needed help, he’d help them.”

Wayne Stevenson was born 51 years ago, the third of five sons in a Hobson ranching family. He never strayed from the Judith Basin, a broad and grassy plain ringed by low mountains.

He married Marian when he was 18 and she was 16, and they moved into an 8-by-30-foot trailer on his parents’ ranch. Stevenson worked for his father but was paid only in livestock, so the newlyweds raised cash by hand-milking cows and raising bum lambs, castoffs rejected by ewes.

They also reared a family: first Valerie, then Doug and Clint.

By 1972, they had saved enough to buy their own ranch, a modest spread of about 1,500 acres and 150 cattle. They named it the Basin Angus Ranch and raised purebred Black Angus cattle for breeding stock.

With an unerring eye for cows, a knack for salesmanship and an enthusiasm for 15-hour work days, Stevenson steadily expanded his ranch to 25,000 acres. The trailer home is long gone, replaced by a big house with five bathrooms and an indoor swimming pool.

But Stevenson was not softened by success. At 51 he was still as sturdy as a post, with calloused hands and a rancher’s tan, his forehead white beneath the shade of an ever-present cap.

He’d rouse friends with phone calls before dawn, declaring, “Early’s all over by 6 a.m.”

Last winter, when it was 40 below, he was outside all day, hustling pregnant cows to shelter until his hands turned numb.

Ranch hands say Stevenson never asked them to work harder than he did, and he was as loyal to them as they were to him.

“He never fired a person, even when some of us thought he should,” Marian Stevenson said.

He hired 32-year-old David Llamas Blake last year, putting him and his family up in a house across the road from the calving shed. Stevenson liked Blake. He worked hard and kept the house in good repair.

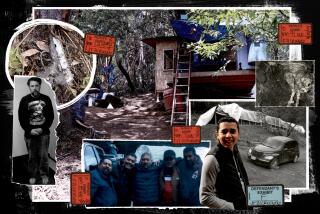

What Stevenson didn’t know was that Blake was a wanted man. California authorities say he was a “coyote” who smuggled Mexicans across the U.S. border for a fee. They believe he killed a man in 1986, shooting him in the head because he didn’t pay.

The night of March 27, soon after Marian Stevenson got the ransom call, she phoned Blake at his house. No, Blake said, he hadn’t seen her husband, but he promised to go look.

He didn’t find him. Neither did the army of ranch hands, FBI agents, sheriff’s officers, tracking dogs and pilots who scoured the ranch for the next 36 hours.

It wasn’t until Tuesday afternoon, when a skittish horse pawed up some manure in its lean-to, that Stevenson’s body was found.

Investigators quickly zeroed in on Blake. FBI agents traced the ransom call back to Blake’s house, and authorities say there was blood on Blake’s clothing, blood in the calving shed, and blood on a front-end loader sitting next to Blake’s house.

Charged with murder and kidnaping, Blake is being held without bail while awaiting trial. Authorities say they’re still trying to determine whether others were involved in what one called “a bungled abduction.”

In the meantime, Stevenson’s family and friends, nearly everyone within a 50-mile radius of Hobson, struggled with questions of their own.

“There’s no explanation,” Marian Stevenson the day after Blake was charged. “It’s just an evil, and we can’t find why.”

After the murder, Hobson’s few gathering spots were busier than usual. Some people just sat and stared. Others quietly swapped Wayne Stevenson stories.

Tess Brady said she’ll miss his jokes, even the ones at her expense.

Randy Morrow, owner of the R & R Ranch Cafe, will miss Stevenson’s daily theatrics when he ordered pie. “Now don’t put that on the tab,” he’d say, “or my wife will find out for sure.”

Stevenson’s wife and brothers and children and grandchildren--all in Hobson and most in ranching--will miss the man who always made time for family, even after long days in the field.

“I feel a great loss,” Marian Stevenson said. “But many people never know a love like we had for so many years.”

Mourners squeezed into the Hobson High School gym, the largest hall in town, for the funeral. But it was not big enough for some old cowboys, who stood and watched from the parking lot, shy of crowds and closed-in places.

A horse-drawn hearse carried Stevenson past nubby fields softening with the first green hints of spring. He was buried by the Judith River, in a quiet spot where the wind rustles through the cottonwoods.

The day of the funeral, Doug Stevenson drove out to the calving shed where his father was killed.

It was not for sentimental reasons. Newborn calves, jet black and still wet from the womb, hobbled around the pens. Doug chased after them, clamping tags into their ears.

“My dad would be disappointed,” he said, “if we didn’t get all the chores done.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.