New Life Centers Named in Suits by Ex-Patients : Litigation: Laguna-based Christian therapy program denies responsibility--or liability--in the sex-related cases.

- Share via

The 25-year-old woman says she was so confused and depressed two years ago that she couldn’t function day to day. She’d cheated on her husband out of an inexplicable loneliness; she’d overdosed on codeine just to make the pain stop.

The television ad promoting Christian therapy offered her hope.

“I thought, ‘Well, maybe they could help,’ ” she said. “ ‘I need to get back with God, to be the person I used to be.’ ”

The woman, who lives out of state, said she telephoned New Life Treatment Centers and an intake worker urged her to come to Buena Park for inpatient treatment. Later, once she’d obtained health insurance coverage, she was told she qualified for a free plane ticket and a waiver of her 20% insurance deductible, she said.

“At the time, I thought, ‘That’s great!’ ”, the woman said. What she wanted “was spiritual guidance, some place to grow spiritually and get better.”

What she got, she claims, was a devastating experience that derailed her marriage, dimmed her faith and dashed any hope she felt she had for a happy life.

In July, the ex-patient sued New Life and a Buena Park hospital in which it operates, alleging a hospital-employed mental-health worker seduced her into an emotionally abusive sexual relationship. She is one of six former New Life patients in five years to formally accuse care providers they met in two New Life inpatient programs in Orange County with sexual misconduct or developing inappropriate, damaging relationships with patients.

Four lawsuits in Orange County Superior Court targeted the same mental health worker; another suit, now settled, alleged a male therapist had sex with a male patient who sought to rid himself of homosexual urges; and a criminal case this year ended in conviction of a therapist who impregnated a former patient. That patient also has sued the therapist, New Life and others.

Representatives of Laguna Beach-based New Life, which has advertised the Buena Park program on Christian radio as “Christians helping Christians” and “a safe place” for therapy, deny the organization bears any responsibility--or liability--in the cases.

Although New Life founder Stephen Arterburn admits three care providers developed “inappropriate relationships” with patients they met in New Life programs, he said the relationships did not take place during the patients’ stays with New Life. The organization could neither have foreseen nor prevented what occurred outside the program, he said.

Arterburn maintains New Life offers a more secure environment than other psychiatric providers because of its spiritual orientation. “The idea that you would be safer in a Christian program is true,” he said.

The allegations, Arterburn said, come from “individuals with serious psychological and emotional problems” prone to distortion and driven by greed. Arterburn said New Life did all it could to protect patients by thoroughly checking the backgrounds of its care providers, giving patients every opportunity to register complaints, and barring workers accused of wrongdoing from its units and referral lists as soon as complaints arose.

“You can’t completely screen out human frailty,” said New Life attorney John Loomis.

But from a Christian organization, plaintiffs said, they expected far more.

They were drawn to New Life precisely because they felt it promised something special: a safer, more comfortable environment in keeping with their spiritual values. As distressed people with an abiding faith in things Christian, several said, they were wide open to the most destructive sort of exploitation. New Life, their lawsuits allege, failed to protect them.

“I was naive, thinking that most things labeled Christian are going to be down-to-earth, good, healthy things,” said one disillusioned 22-year-old plaintiff, who like all other plaintiffs in this story spoke on condition of anonymity.

*

Therapy, by its very nature, is a secretive process: therein lies its promise, and therein its dangers. Experts say no institution, religious or secular, can guarantee safety to a patient in that intensely personal and private interaction, although careful training and monitoring can head off problems.

In nationwide anonymous surveys of more than 5,000 therapists, nearly 7% of males and 2% of females have admitted to sexual intimacy with patients--rough estimates at best.

In California, the special vulnerability of therapy patients was recognized in a 1989 law, prohibiting therapists from having sex with them during treatment and for two years afterward. Patients often are attracted to their therapists, with whom they share their most intimate feelings, but it is up to therapists, under the law, not to take advantage of the attraction.

In New Life programs, advertised around the country on Christian radio and television, there was a promise--implied or explicit--of special protection, plaintiffs and their attorneys argue.

“At the time I didn’t trust the secular unknown,” said a 29-year-old former Christian schoolteacher, impregnated last year by a therapist she met at the Buena Park program. “I was very simplistic in my thinking. . . . I only put my trust in Christian counselors.”

Plaintiffs contend their faith was deliberately exploited by those seeking to seduce them. The 25-year-old out-of-state patient, in her suit, accuses New Life of fraudulent advertising. The religious message, she said, falsely led her to believe she would receive care in a “safe and secure environment.”

Now, she said, “I don’t trust anybody anymore. . . . I try to go to church now and trust the preacher, but I’m thinking, ‘I can’t even trust him. Who knows what he does’ (after the service is over)?”

It doesn’t matter, several plaintiffs and attorneys said, that no sex occurred within the walls of the program. That is where the patients met the accused care providers who, according to several lawsuits, were improperly screened or supervised by New Life. And that is where the scheming and exploitation began, the former schoolteacher’s suit alleges.

Arterburn said that New Life itself was “betrayed and victimized” by the three men accused of wrongdoing. Though New Life attorneys and its marketing director insist most of the allegations are unproven, Arterburn acknowledged in a letter to The Times that the three men developed “inappropriate relationships” with patients.

“I cannot stress enough how appalled and saddened we are by this,” he wrote.

New Life attorney Loomis suggested the plaintiffs may bear some responsibility themselves, questioning their “possible roles” in “consenting to or encouraging the acts . . . for which they now say they’ll gladly take money.”

New Life took every precaution, Arterburn said, by providing intensive orientation, multiple layers of supervision and ongoing classes for workers, for example, and setting up a patient complaint line. The organization has a policy against touching patients.

The accusations, Arterburn said, are inimical to New Life’s mission: to “empower . . . patients” who often are skittish about secular therapy, and help them overcome “victimization.”

Today, New Life operates as The Minirth Meier New Life Treatment Clinics, having merged in January with nationwide Minirth-Meier Clinics, which is not named in the lawsuits.

Considering that New Life has treated more than 11,000 patients at two Orange County programs since 1988, it has had few complaints, Arterburn said. Malpractice claims are so rare, he said, that New Life’s insurance rates are lower than other psychiatric providers and drop annually. New Life officials, however, declined to provide any supporting documentation, saying the organization’s insurance provider did not want rate comparisons made public.

*

Plaintiffs said they went to New Life assuming they had entered a safe harbor in their otherwise turbulent lives. Two patients said that coming to the realization that they were being hurt, not helped, was a long process. The two alleged they quietly engaged in sexual activity with their therapists for about a year before calling it off.

One, a young Riverside man then seeking to overcome homosexuality, said he did not come forward for months--and even did testimonials for New Life--because he had bonded with his therapist, John Lybarger, and feared he could not live without him.

“I was completely blinded. . . . I was very needy and I was not connected with my feelings,” he said. “He was the only one reaching out to me in a quite unconditional way.”

The former Christian teacher said that before she became pregnant by therapist James Lisle, she believed his admonition that their relationship was a sacred covenant which it would be a sin to reveal, according to her testimony at Lisle’s state disciplinary hearing.

Lybarger, who paid $115,000 in 1991 to settle the case against him, declined comment. Lisle, convicted in February of having sex with a former patient and sentenced to a year in jail, contends the relationship was consensual and occurred after treatment ended.

In general, experts say, patients commonly become unwitting conspirators in their own abuse, failing to come forward with complaints out of misplaced loyalty and love, or because they are ashamed.

Among therapists, outward signs of trouble can be subtle, said Andrea Celenza, a Massachusetts psychologist who treats errant therapists. Institutions need “alert and substantial” training programs to pick up on such signals as neediness or narcissism, she said.

Arterburn insisted Lisle and Lybarger gave no hints of being troubled. Both held marriage, family and child counselor’s licenses and had clean disciplinary records with the state Board of Behavioral Science Examiners; both had malpractice insurance. Despite “lengthy and thorough” background checks by New Life, hospital credentialing committees and medical staff panels, no blemishes marred their records, he said.

But Lisle had a past that the patient’s lawyers contend New Life and Orange County Community Hospital in Buena Park should have known about. For 3 1/2 years, Lisle said he was on staff for 3 1/2 years at the hospital, where New Life has a 50-bed program.

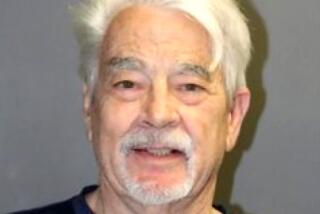

The 67-year-old therapist, who had been an independent contractor with New Life, candidly testified during his disciplinary hearing that he had been fired from his job as a welfare director in Ohio in the late 1950s because he impregnated a client he was counseling. And he said he was asked in 1969 to resign another position in California after his boss became aware he had a “love relationship” with a client, whom he later married.

Speaking in a confident baritone at his September hearing, Lisle said he was hospitalized for nine months in an Ohio mental institution in 1958 after being “personally attacked” by demons. He said he was miraculously cured by a Christian psychiatrist, was “born again” and hasn’t needed therapy since.

Lisle’s sister, however, had told her brother’s probation officer that he has suffered lifelong mental illness and had been diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. “Why doesn’t anyone see how sick he is?” she asked, according to an April, 1994, probation report.

A state medical board investigator, also quoted in the report, said Lisle’s affiliation with a Christian program was like “putting a fox in the hen house.”

Arterburn and Craig Dummit, Orange County Community Hospital’s attorney, said they first heardof Lisle’s problems when he was arrested in October, 1993. He was immediately barred from the premises, they said, and later resigned from the hospital staff.

Lisle, Arterburn said, was “a master at hiding the truth.”

Lisle only hinted at his past problems when he applied for a counselor’s license in California in 1967, saying “there was an apprehension of an accusation of unfaithfulness” by his wife a decade before. But “the charge” was dropped, he wrote.

Scott Syphax, acting executive officer of the state Board of Behavioral Science Examiners, said licensing authorities determined there was no criminal conviction involved and did not pursue the matter. An applicant would be much more rigorously screened today, Syphax said.

But, he cautioned, licensing means a counselor meets the minimum requirements; it is not a “Good Housekeeping seal of approval” assuring patient safety.

*

The other former New Life therapist accused in a lawsuit of sexual misconduct was a sexual addiction specialist, prominent in the therapeutic community and apparently well-respected by peers. In contrast to Lisle, Lybarger was not accused of a crime and had no record of past problems.

The first clinical coordinator of New Life’s program at Western Medical Center-Anaheim, Lybarger came “highly recommended,” Arterburn said.

The patient he allegedly victimized, then a 21-year-old husband and father of an infant, “was expressly solicited into the New Life treatment program for (treatment of) homosexuality,” according to a letter from his lawyer in court files. But after completing a six-week stay in New Life in 1989, during follow-up outpatient care, Lybarger “proceeded to engage (him) in a totally unprofessional sexual relationship,” according to the letter.

While the sexual relationship progressed behind closed doors, according to allegations filed in court, New Life “engaged” the young man to give testimonials about his treatment.

The patient was “commercially exploited” and his case history was improperly used in written materials, videotapes and public presentations to solicit new business, according to the suit.

Arterburn said the young man was never told he could be “cured” of homosexuality. Rather, he said, the patient had “issues more pressing” than his sexuality, including a cocaine addiction. By all appearances, Arterburn said, he had been very happy with New Life and volunteered to do testimonials.

Arterburn said his first inkling of a problem came when the lawsuit was filed by the man and his wife in November, 1990--long after both the patient and Lybarger had left the New Life program. “I want to be very clear that nothing of a sexual nature occurred . . . while (the young man) was a patient in our program,” Arterburn said.

Although Lybarger paid $115,000 to settle the case, New Life attorneys say they separately settled this year for less than $30,000, purely to avoid the costs of trial. Western Medical Center-Anaheim was named as a defendant but not served with a lawsuit.

*

Four other lawsuits against New Life programs and Orange County Community Hospital in Buena Park target a man who had no license to practice therapy at all.

Nevertheless, lawyers for the plaintiffs--young women treated between January and September of 1993--contend mental health worker Gregory Rundhaug abused the therapeutic role with ruinous effects.

Rundhaug, three plaintiffs said, ran group therapy sessions and portrayed himself as a therapist. According to the lawsuits, he then tried to form sexual or other inappropriate relationships with the plaintiffs. New Life and the hospital, they allege, failed to properly supervise or stop him.

Rundhaug, a hospital employee who worked in New Life’s 50-bed unit, seems to have disappeared, his attorney said. Rundhaug could not be reached for comment.

Arterburn said that Rundhaug did not work as a therapist. He was a “group facilitator” and led talks or gave lectures, not group therapy.

The mental health worker is accused in the lawsuits of forming so-called “dual relationships”--liaisons with patients outside the context of therapy--of using therapy as a guise for romantic overtures and, in one case, of having sex with a patient.

Two of the women’s suits contend Rundhaug used his experience with them as patients, their faith as Christians or their perception of him as a therapist to push them into dramatic--and destructive--changes in their lives.

The lawsuit by the 25-year-old out-of-state woman, who came to the Buena Park program in part to work through emotions that led her to cheat on her husband, contends Rundhaug seduced her by leading her to believe sex was an “essential part of her therapy.”

He “thought I was beautiful,” the woman said. “That really made me feel good. Here he was, this therapist. He was respected. I thought, wow, he likes me out of everyone else. I felt like I kind of wanted to be with him. I couldn’t wait to see him.”

He is “one of these guys who knows what you want to hear. I wanted a closer relationship with God. . . . He told me about his relationship with God and quoted Scripture.”

Rundhaug held “little (private) sessions” with her in the hospital, once kissing her in a locker room, she claims. After her second 10-day stay at the Buena Park program ended, she contends, he persuaded her to miss her plane home and have sex with him at his home.

In September, 1993, she said, after she had returned to her husband, Rundhaug sent her a plane ticket back to California. She stayed with him for about two weeks before deciding to try to salvage her marriage. “We’re still married,” she said, “but not really. We hardly talk. . . . It makes me feel very lonely and very guilty. . . . Even to this day, I think about suicide.”

A 22-year-old woman, who came to New Life from Pennsylvania in January, 1993, after hearing an ad on Christian television, contends in her suit that Rundhaug took advantage of her “vulnerable mental state” by “inducing” her to live with him after her release.

During her stay at New Life, according to the woman’s testimony in an October deposition, Rundhaug gave her Valentine’s cards, met with her frequently in the courtyard and accompanied her on outings. “Logically, I think someone (from the hospital) should have known” he was behaving inappropriately, she testified.

Rundhaug sought her trust, she said in an interview, by telling her he was a therapist. Then, she contended, when she left her job and family back East to move in with him, he tried to start a romantic relationship. After she rebuffed him, she said, he kicked her out.

Rundhaug wasn’t stopped, plaintiffs said, until three of them learned about each other’s encounters with him, in part through mutual friends and the help of a New Life counselor. They said they made formal complaints around August, 1993, to the program administrator.

Arterburn said that far from ignoring the problem, New Life helped the women make a videotape chronicling their complaints. Rundhaug, on vacation at the time, never returned to his job to answer the accusations and ultimately was fired, Dummit said.

On the videotape, Arterburn noted, none of the women say a sexual relationship occurred while they were under New Life’s care. Until the complaints surfaced, New Life and hospital officials said, Rundhaug was considered an exemplary worker. He had a file “replete with letters from patients singing his praises” and a “near-perfect” three-month review, said hospital attorney Dummit, who also represents Rundhaug.

Dummit said Rundhaug may have violated hospital policy but did nothing illegal or unethical because the 1989 law and professional ethical codes do not apply to non-therapists. Regardless, he said, the hospital is not liable because the allegations relate to activities by Rundhaug off the premises and were “outside the scope of his employment.”

*

The improprieties of three care providers, Arterburn said, should be seen in the larger context of an organization that over its six-year history has helped thousands of people “make dramatic changes for the better in their lives.”

Arterburn said he is “deeply disturbed” about a depiction of New Life drawn by people who are “attempting to get money from our company.” A more accurate portrait, he said, would come from satisfied patients and employees who see their jobs as “a mission and a ministry.”

But regulators and experts say a religious setting is no sure shelter from therapists or others who prey upon patients’ vulnerabilities.

Mixing religion and therapy can be “a powerful force for improving people’s lives,” said Syphax of the Board of Behavioral Science Examiners. But it can also can render patients “extra vulnerable” to exploitation, because the therapist is endowed, in the patient’s mind, with extra credibility and power.

“In my work,” Celenza said, “I have found it is not institutions that are safe or unsafe. It’s the people” working inside.

* NEW LIFE THERAPY LAUDED: Combined psychiatric and spiritual therapy draws praise. A18

Therapy Warning Signs

The state Department of Consumer Affairs has developed a booklet titled “Professional Therapy Never Includes Sex” to help patients sexually victimized by psychotherapists. In some sexual-abuse cases, other inappropriate behavior comes first. While the therapist’s behavior may be subtle or confusing, it usually feels uncomfortable to the client. Here are some warning signs:

* Telling sexual jokes or stories

* “Making eyes at” or giving seductive looks to the client

* Discussing the therapist’s sex life or relationships

* Relying on a client for personal and emotional support

* Sitting too close or lying next to the client

* Inviting a client to lunch, dinner or other social activity

* Scheduling late appointments so no one else is around

* Giving or receiving significant gifts

* Providing or using alcohol or drugs during sessions

* Hiring a client to do work for the therapist

* Bartering goods or services to pay for therapy

* Any violation of the client’s rights as a consumer

The booklet is available through the Medical Board of California at 1426 Howe Ave., Sacramento, Calif. 95825; or the California Board of Psychology at 1422 Howe Ave., Suite 22, Sacramento, Calif. 95825, or the Board of Behavioral Science Examiners, 400 R St., Sacramento, Calif. 95814.

Source: California Department of Consumer Affairs

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.