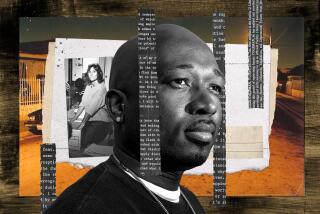

Slain Loan Figure a Study in Contradictions : Memorials: William Hankins, who died in ambush, is eulogized as a success story. But others say he defrauded them out of their homes.

- Share via

Police listed William Hankins’s age as 51 after he was gunned down next to his Mercedes, in front of his ocean-view Pacific Palisades home, but he was really 44, his family insisted later--the mistake stemming from a bit of fiction that dated to his “dirt poor” youth, and determination to escape it.

As the family lore had it, Hankins was 13 or so when he went to the DMV office and convinced workers that he was old enough to drive. Thus he got a license listing a fake birth date in 1944, and with it a jump on his peers in the inner city: soon starting a family, having four children by the time he was 20, and launching his own real estate loan businesses.

Before long, despite just an eighth-grade education, Hankins was reporting ownership of 45 houses and 15 apartment buildings, and moving his family to the hilltop in the Palisades, with the pool in back, and sight lines to the Palos Verdes Peninsula. By the time the 6-foot, 230-pound Hankins was ambushed there last weekend, the gunshots reverberating through the million-dollar neighborhood, he claimed an income of $200,000 a month and was taking his business nationwide.

“In many ways, this guy was an amazing guy,” said Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., one of Los Angeles’ best-known attorneys these days, who counted Hankins as a client and a friend--and who spoke at his funeral service Friday. “This guy’s a success story, I’ll tell you.”

So why then, before Hankins was even in the ground, were some others hardly eulogizing him? They were saying after his murder, openly and without apology, things like: “That’s the best news I’ve heard in a long time” and even, “There is a God.”

The latter was offered by Elena Ackel, who was among a small army of lawyers who had battled Hankins during the last 15 years over how he made his fortune: a series of court cases alleged that he promised to help struggling homeowners in Los Angeles’ poorest communities, only to defraud them out of their homes.

The lawyers’ files were filled with the sad stories of families, widows and the elderly who had lost their homes. Some of the complaints made it to the Los Angeles County district attorney’s major fraud unit, which had a 17-count criminal case pending against Hankins at his death.

“I’m sure if I knew the Bible better there would be something in the Old Testament that is more applicable,” Ackel said. “But I’m not sorry to see him dead.”

“He did make a lot of enemies,” said Eugene R. Salmonsen Jr., one of Hankins’ lawyers. “He was a tough negotiator. . . . If you defaulted, he foreclosed.”

With Los Angeles police still searching for clues in the Jan. 6 slaying, Salmonsen said he believed they should look among Hankins’ business enemies. In fact, Hankins had complained in September that one of the alleged victims listed in his indictment had threatened his life--and that his Inglewood offices had been riddled with gunshots a few days later.

So on one point, at least, Hankins’ detractors are in total agreement with his own attorney--that detectives should look to the real estate records.

“Are there any suspects?” Ackel asked. “Try the phone book.”

*

*

Even after he had an impressive fleet of cars to carry him about town--no less than two Rolls-Royces and four Mercedes--Hankins liked people to know how he was born in poverty in Pensacola, Fla., then raised in poverty in Los Angeles. The man known as “Willie” and “Bill” to his family, sometimes “Big Bill” to others, rattled off the story of his humble roots to business friends and adversaries alike, even to the local shoeshine man--encouraging the guy “to keep hustling.”

Hankins apparently learned that lesson early, telling one attorney that as a youth he would pick up clothes in Downtown L.A., then sell them on street corners. Records show he also had run-ins with the law starting at age 11, and chalked up a felony conviction a decade later, for counterfeiting $10 and $20 bills. He drew a 90-day sentence and three years probation.

It was during that probation, that Hankins began to amass real estate. According to one lawyer who battled him, Hankins spoke of learning the ropes from the absentee landlords who controlled chunks of housing in the inner city. Later, when Hankins’ own ways were challenged, he complained that he was picked on for doing nothing different than the outsiders.

“He said there was a group of white property speculators called the ’40 Thieves’ who would buy up property at foreclosure for a pittance . . . and they had trained him,” said John Daum, a partner with the O’Melveny & Myers law firm who filed, for no fee, a wide-ranging civil suit against Hankins in 1979. “(He’d say) ‘why don’t you pick up on the property speculators who grew up on the Westside rather than those who grew up in the ghetto?’ ”

*

The lawsuit combined complaints collected by various lawyers that their clients had been cheated out of their homes by Hankins. Ackel, who tended a Legal Aid office in South-Central, said “hardly a week would come by when someone didn’t say they were ripped off.”

As Hankins’ lawyer described it at the time, he was merely a “super hustler” who rose at 5 a.m. to read foreclosure notices, then knock on doors of the troubled homeowners. Some got letters promising “A RAY OF HOPE,” meaning a loan to pay the mortgage.

“His approach to them was, ‘I’m a brother. I can help . . . you can’t count on white lenders to help you refinance,’ ” said Muncie Marder, another attorney who helped assemble the case against Hankins.

Some homeowners alleged, however, that they were given stacks of paperwork to sign, including--unknown to them--a deed turning over their house. They would be given the opportunity to rent back their homes--for payments higher than the mortgage that had gotten them in trouble.

Ackel said Hankins actually held one woman’s hand as she signed papers in a nursing home.

What amazed Marder most, through the bitter legal fights, was that Hankins never admitted doing “the slightest thing wrong,” and saw himself as an honest victor in the economic battle for survival of the fittest, who only wound up with someone’s property if they did not fulfill terms of his deals with them.

“He thought . . . if he was smart enough to do it, that it belonged to him,” Marder said.

Nonetheless, in 1980, Hankins agreed to a settlement of the civil suit under which more than 30 homeowners got back their property. The settlement also called for him to pay $424,000 to about 70 plaintiffs--although attempts to collect those funds prompted yet another decade of litigation.

By all accounts, Hankins took an aggressive stance in his legal battles, much as he had in real estate. After facing endless questioning at one deposition, he had his attorneys sue the opposing counsel, in part so he could take their depositions.

Through the 1980s, he continued to build his empire--and generate new complaints.

“Oh yeah, he had quite a few lawsuits against him,” said Hankins’ attorney Salmonsen, attributing the litigation to “the nature of real estate in Los Angeles” and publicity generated by Hankins’ legal problems, which only encouraged others to seek a piece of him.

While the grumblers drew the public attention, Salmonsen said, Hankins had “a tremendous number of (satisfied) investors . . . with him 10, 15 years” and a construction crew that would improve property.

“He always kept his word with me,” said Cochran, who added that he never saw the “side of (Hankins)” that drew the passionate condemnations. The Hankins he knew, Cochran said, was a “very gregarious” man not afraid to take an unpopular stance--for instance, he was a “big Republican” in L.A.’s black community--dedicated to his family and charitable to those less fortunate.

“At Thanksgiving, he called me up and said, ‘Johnnie, I’m going to send you some smoked turkeys. . . . Do what you want with them,’ ” Cochran said.

A shoeshine man down the street from Hankins’ one-story, white-stucco office building in Inglewood also had fond memories of the real estate mogul, who would drop off his cowboy boots and offer encouragement.

“He sent me a lot of customers,” the shoeshine man said, declining to give his name. “Everybody’s talking bad about him. (But) people losing their houses and all, that’s not up to him. He probably helped a lot of people get homes.”

Indeed, one of Hankins’ sons, Demetrius, said the family had received numerous testimonials in the wake of his murder, from “everybody in the whole city, from congressmen to everybody.”

The son was angry at how some besmirched his father’s name.

“None of that stuff was ever proven,” Demetrius said. If some were spiteful of his father, there was a simple explanation: “Because they couldn’t beat him.”

*

*

Allegations with a familiar ring, however, continued to haunt the elder Hankins.

The criminal charges were contained in a 1992 indictment and covered dealings from 1987 to 1990, alleging offenses such as “Grand Theft of Real and Personal Property” and “Fraud or Unfair Dealing by a Foreclosure Consultant.”

Cochran said he was surprised criminal charges were filed over “civil things,” while Salmonsen, who also was working the case, said, “I fully expected him to be acquitted.”

In typical style, Hankins had gone on the counterattack, filing a suit against the county--which is still pending--alleging that district attorney investigators, serving a search warrant at his home, roughed him up and mistreated his wife by failing to give her “an opportunity to put any clothing on, or to use the bathroom.”

The Hankins apparently were not the only ones upset with the course of events.

At a Superior Court hearing in the criminal matter last Sept. 14, an attorney reported that up to eight gunshots had been fired through the windows of Hankins’ office building two evenings earlier--soon after one of the alleged victims made “extremely volatile” calls complaining that he was owed at least $16,000 and “wanted to resolve matters.”

“He made phone calls to my home,” Hankins told a judge. “He threatened to kill me and my wife.”

A month earlier, one of his three sons had been involved in a shooting with more serious consequences.

Willie Darnell Hankins, 28, faces a murder charge in the Aug. 3 shooting of an associate who showed up at his own offices, on Wilshire Boulevard, demanding $28,000 from a real estate deal, according to testimony at a preliminary hearing.

The man’s widow, Kimberley Lightfoot Hill, testified at the hearing that she did not believe the deal was “on the up and up” and that her husband was threatening to expose that fact if not paid.

Cochran, who is representing Willie Hankins, said he will argue self-defense when the murder case comes to trial.

In the shooting of the elder Hankins, Los Angeles police are saying little. “We’re just working on the case,” said Detective Ron Phillips.

Also assigned to investigate the death of Hankins, ironically, is Mark Fuhrman--the detective Cochran and other defense attorneys have targeted for his work in the O.J. Simpson murder case.

Salmonsen said Hankins had just “stepped out of his car. The perpetrator was in the bushes . . . (and) stepped out and fired.”

A couple across the residential canyon, who were outside taking down their Christmas lights, reported hearing at least 10 shots.

The fusillade left Hankins dead at the scene, and also killed the family dog.

Friday’s funeral did not ignore the “air of controversy” around Hankins, as his daughter wrote in the program for the services at Marina Cathedral in Los Angeles. But the theme of the afternoon was how the man in the brown and gold casket had risen “from the Everglades to the Palisades,” and assisted others along the way. He also taught his children that they could accomplish anything--whether on the “football field or courtroom”--and rise to “that next level that the Hankins family talked about every night at dinner,” son Willie Hankins Jr. said.

“He did a lot of good and didn’t ask a lot of credit,” said Cochran, who rushed from the Simpson trial to the service. He told mourners that he frequented the barbershop across the street from Hankins’ office and, “Before I got up he’d pay the barber and go on his way. He was really larger than life.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.