Making a U-tah Turn : Jazz Left New Orleans For the Wilderness Then Helped It Bloom

- Share via

SALT LAKE CITY — Picture the patriarch searching for a haven, cresting the surrounding mountains and looking down into the valley upon the present site of a bustling city.

He wonders just one thing. . . .

Where is he going to find a deli in this Godforsaken wilderness?

Not only that, do they have Italian food in Utah? And just where is Utah , anyway?

“There was no deli,” says Jazz President Frank Layden, remembering those frontier days of 1979. “In fact, we were lucky we had pizza. I thought Utah was in Europe. No really, it was just unbelievable.”

Professionally, things looked worse. Layden had taken a job as general manager of the New Orleans Jazz. But before he could put his first rookie on waivers, his franchise was moved from the epicurean, never-a-dull-moment French Quarter to Utah, where they once had an ABA team, which folded, and dullness looked like a civic aspiration.

Presumably, the Jazz selected Utah because there was no arena on the dark side of the moon. Having failed in a small market, owner Sam Battistone (a Mormon, although he lived in Santa Barbara) found a smaller one. For good measure, he kept the name--Utah Jazz?--giving his franchise one of the bad starts in sports history.

Since then, it has had one of the great rallies. The Jazz now has a new 19,000-seat arena, which it fills nightly. It has averaged 52 victories the last seven seasons and is one of two teams, with the Portland Trail Blazers, that never has been in the lottery.

Because kids do not come out of school saying, “I must see Salt Lake City!” one might ask how Jazz officials did it.

They out-thought everybody or got lucky or, best of all, both.

Time and again, they made stars of players others passed on (Karl Malone, 13th pick in the 1985 draft; John Stockton, 16th in 1984) or pulled off the trade everyone wanted (Jeff Hornacek last season), or flimflammed someone out of a useful player (Felton Spencer for Mike Brown in 1993; Adam Keefe for Ty Corbin in 1994).

The wise guys always were writing them off, but today they’re on a 58-victory pace. For thefirst time in years, Malone hasn’t delivered his nobody-here-is-committed-to-winning-please-trade-me speech.

“It’s just luck,” says Jazz Director of Operations Scott Layden, son of Frank.

“It’s something that just happens in basketball. Hopefully, you can stay lucky and things work out. We were taking a lot of heat this summer for being stagnant. This was after we had made the trade for Adam Keefe and signed a free agent, Antoine Carr. And everybody’s saying, ‘Wow, you guys aren’t doing much, you didn’t get Scottie Williams, you didn’t get Robert Parish, Frank Brickowski, Michael Cage.’ For whatever reason, it’s just worked out with these guys.”

*

The first season in town, the Jazz went 24-58 and attendance dropped more than 1,000 from New Orleans. This was no surprise to Frank Layden, who had chosen to be general manager “because nobody could coach this team.”

The next two seasons, attendance dropped from there. The Jazz drafted Dominique Wilkins--and traded him to Atlanta for troubled John Drew and $1 million.

“We were picking third that year (1982) in the draft,” Scott Layden says. “We couldn’t fail, OK? You had James Worthy, Dominique Wilkins and Terry Cummings. We’re picking third, OK? If you’re picking fourth, you’re dead. You get Bill Garnett. Picking third, we can’t make a mistake. The phone’s ringing off the hook, so we know that the pick’s valuable.

“We had to make payroll, so we sold Dominique back to Atlanta.”

In that draft, however, the Jazz used a fourth-round pick for Mark Eaton, a 7-4 benchwarmer from UCLA who at times hadn’t even made the Bruin traveling squad. The next three No. 1 picks were Thurl Bailey, Malone and Stockton. A new power was born.

A new owner, car salesman Larry Miller, came in with a splash. He was a shameless hot dog who specialized in baiting opposing players (then-Jazz executive Dave Checketts, sitting next to him, got in trouble for a crack to Olden Polynice about stealing televisions), and last season disgraced himself by picking a fight with two Denver fans. However, Miller also built the Delta Center and let his basketball people run the basketball end.

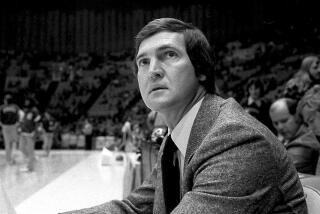

For most of the ‘80s, Frank Layden was coach and general manager. At one time or another, he had input from Checketts, a bright young executive who now runs the New York Knicks; from now-Coach Jerry Sloan and assistant Phil Johnson, a coach of the year himself; and from Scott, who had worked his way from college coach to Jazz assistant, scout and personnel director.

No workaholic, Frank contented himself with laying out the philosophy and keeping everyone entertained with his New Yorker Lost in Utah schtick .

Here, for example, is Frank on Eaton:

“The thing that’s interesting is not that we drafted him, because we drafted him in the fourth round. It was no big deal. But we gave him a guaranteed contract and that’s what Mark needed. . . . One thing I knew when I looked at him, he was tall. I’m not stupid. And he was wide. He was the biggest man in every direction I’d ever seen.

“Louie Carnesecca (former St. John’s coach), a good friend of mine, a long time ago said, ‘Frank, never give up on a big guy. Never!’ So if I’ve gotta have a 12th guy, why not have a 7-4 one?

“I went to the owners, I said, ‘Look, hey, I don’t know, this is not a big investment, but let’s take this guy, let’s pay him some money and three years down the line we’ll make a decision.’ ”

Within three years, Eaton was leading the league in blocks at 5.6 a game, more than doubling the average of second-place Hakeem Olajuwon at 2.7.

Frank never saw Eaton in college. Nor did he see Malone, a raw prospect from Louisiana Tech who looked small for an NBA center, taking him on Scott’s recommendation.

“My son told me, ‘We got to get this guy because this guy is what we don’t have, he’s mentally tough,’ ” Frank says. “When he started to slip to us (in the draft), I thought everybody must have known something we didn’t know. I said, ‘Is there something we’re not aware of?’ I wish I could tell you we knew what we were getting.”

Frank saw Stockton in a tryout camp but wasn’t overly impressed; he took him on the recommendation of friends in college coaching who had seen the unknown from Gonzaga survive a cut at Bobby Knight’s Olympic camp.

“We got Stockton because we thought he was a good backup for Rickey Green,” Frank says. “Green was the All-Star guard. . . . But afterward, it became very evident that this guy was some tough guy. It wasn’t long before he was having some battles with Rickey Green.”

When Checketts got the Knick job, New York writers asked who had been responsible for the deft personnel work. It was all of them, and no one.

“They were trying to pin down who drafted Stockton and Malone,” Scott says. “They wanted to see if (Checketts) was the guy. My dad was the guy who was in charge of the organization, but what I said at the time, ‘You know what? Those two players in ’84 and ’85 were a gift from God.’ ”

After that, however, the Jazz officials were on their own and up to the task.

When Eaton wore out, they came up with Spencer.

In need of a third option, they got Jeff Malone for Eric Leckner, Bob Hansen and a No. 1 pick.

When Jeff Malone slowed down, they traded him and his 19-foot range for Hornacek, the long-sought three-point threat. “One of the reasons we’ve had a lot of success, it’s easy to play with Stockton,” Scott Layden says. “It’s easy to play on the same team with (Karl) Malone. ‘Cause we’ve got two supers and they can carry some lesser players and win games.”

Unfortunately, they didn’t win as many in postseason play and their pound-it-in-to-Mailman offense was called “predictable” so often, it was beginning to sound like a new name: “. . . the Rockets easily dispatched the Predictable Utah Jazz.”

Of course, who isn’t predictable? The Rockets throw it to Olajuwon in the crunch, the Magic to Shaquille.

The Jazz has never been deeper or more efficient, even if it has lost Spencer, its only legitimate center. And if things don’t work out, the guys in the front office may think of something. So far, they always have.

*

Who’d have thought it? Utah turned out to have a civilization capable of sustaining a New Yorker, even if he has to bring back Nathan’s hot dogs from trips East.

Now, there are even a couple of delicatessens.

“They don’t have rye bread yet,” says Frank, now a ceremonial presence in the front office.

“That’s the truth. You cannot get rye bread here. You cannot make a sandwich. You order a sandwich, they put it on sourdough. The bread is thicker than the meat is.”

On the other hand, he’s a civic treasure.

“As one very prominent Mormon official said, ‘Frank Layden is great, he brought us a sense of humor,’ ” says Frank Layden.

It’s a great responsibility, but he can handle it. The air is cleaner, the people friendlier, it doesn’t cost $15 a day to park at the airport and the Jazz is still in there swinging. Who could ask for more?

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.