Growing Up With Sickle Cell Disease : At an Age When Peer Acceptance Means Everything, Thousands of Youths--Most of Them African Americans--Feel Like Oddities as They Cope With an Illness That Robs Them of a Normal LIfe.

- Share via

Marc Hull was too young to remember his first sickle cell crisis. It was Jan. 3, 1979, and he was 18 months old.

He had a temperature of 107, his mother, Melva Leflores, recalled. He was near death, suffering from a host of related complications: blood and bone infections, salmonella and pneumonia.

Now at 17, having endured several dozen painful attacks in his short life, and making monthly visits to the hospital because of problems with his bones and tissues from sickle cell disease, Hull is fed up with his illness.

“I’m not normal because I have an illness,” he said. “Normal don’t have to worry about doctor’s bills or ‘If I have a really bad crisis, will I die? I try to put it out of my mind, but sometimes I still think, ‘Why does this happen to me?’

“When I start thinking about the future, I get worried,” Hull said. “Then I get angry because I wonder why I have (sickle cell disease) and get sick all the time.”

Hull, who lives with his mother in South-Central Los Angeles, is like hundreds of other teen-agers in the city and thousands more in Southern California--most of them African Americans--who must cope with the frustrating, debilitating disease.

There is help, through the pioneering Crenshaw-based Sickle Cell Disease Research Foundation, which provides referrals for treatment and counseling. But the painful incidents, blood transfusions, repeated trips to hospital emergency rooms and the difficulty of explaining the illness to others can be draining and discouraging. Add being a child or a teen-ager to the equation and it becomes almost unbearable.

“Sickle cell disease is difficult for the smaller children, but it’s especially hard for the teen-agers because of the social issues teens go through,” said June Vavasseur, a retired social worker who spent 12 years working with sickle cell disease patients at a County-USC Medical Center.

At an age when image and acceptance by peers means everything, many teen-agers and some younger children with sickle cell disease feel like oddities. As many of them see it, they have been cheated with a life in which they can’t participate in athletics like their peers. They also fear being ostracized by friends if they disclose their disease.

“Their bodies are changing, they’re becoming adults, yet they don’t want to be different. They want to be liked by their friends,” Vavasseur said.

Rafael, a 17-year-old junior at Venice High School, is embarrassed about having sickle cell disease, so much so that for this article, he asked that his first name be changed and that his last name not be mentioned. He has only told one friend about his illness, and he makes up excuses for others.

“It makes me feel like I wouldn’t have as many friends,” Rafael said as he received his monthly blood transfusion. The transfusions reduce the severity of painful attacks, or crises, cause by his sickle cell disease.

“It’s like if I told everyone, then everyone won’t want to hang around with me as much,” he said.

The perception of sickle cell disease is the antithesis of what the disease actually is, Rafael and other youths say.

“People think like if you’re near them or if you spit on them, they’re going to catch something,” one teen-ager said during a recent weekend retreat for teen-agers with sickle cell disease. “It ain’t like that.”

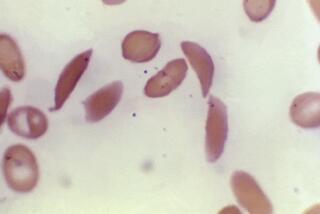

Sickle cell disease is a non-contagious blood disorder caused by a defect in the gene for red blood cells, which carry oxygen throughout the body. Sickle cell anemia is the most common form of the disease.

Though it has become mislabeled as a “black disease” because of the disproportionate number of African Americans with it, sickle cell disease is also found among Latinos, Greeks, Italians (especially Sicilians), in Asiatic Indians, Iranians and Middle Easterners. Those of African, Asiatic Indian or Mediterranean ancestry are most prone to the disease because the genetic defect prospered, ironically, as a natural defense against malaria in those geographic regions.

Each year, in a state-mandated blood test for newborns, about 150 are found to have sickle cell disease, the majority of whom are African American, according to the Sickle Cell Disease Research Foundation. One out of 185 Latino newborn babies have the sickle cell trait, which means they may pass the disease on to their children if their partner also has the trait.

Sickle cell trait itself is asymptomatic, but if both parents have the trait, their child has a 25% chance of having the disease. Nationwide, experts estimate that about 72,000 blacks have sickle cell disease. One in 12 African Americans in Los Angeles has sickle cell trait, and about 5,000 suffer from the disease in Los Angeles and elsewhere in Southern California.

Sickle cell disease affects each person differently, although almost all experience periodic painful crises, some more frequently than others.

Defective cells become rigid as they become sickle shaped. They clump, jamming the narrow capillaries and blocking the delivery of oxygen to tissues all over the body. They become like thumbtacks trying to flow through a rubber pipe. This often results in bone-crushing pain and organ damage.

Most crises eventually abate on their own, as the sickle cells break down and blood flow improves, bringing new oxygen. Severe crises require morphine for relief or even hospitalization, often causing children to miss days and sometimes weeks of school. Each crisis, no matter where it localizes, attacks the organs. Some children lose their spleens and, later in life, their gall bladders or other organs. Some crises are fatal.

Life expectancy for sickle cell victims averages about age 40 for men and 50 for women. However, children as young as 7 occasionally die from strokes, infections and pneumonia because of the disease, doctors said. Pneumonia can kill an infant who has sickle cell anemia with devastating quickness.

“The incidence of death in children is lower than adults, although it does occur,” said Dr. Tom Coates of Childrens Hospital. Coates said painful crises increase in the first 10 years and hit their peak in the late teens and early 20s.

“It is so painful to see your child in pain . . . and know that you can’t do anything to help them,” said Stella Ekwunife of Reseda as she waited in Childrens Hospital recently while her son, Obinna, received a blood transfusion to help lessen the number of painful episodes from sickle cell disease.

Two of Ekwunife’s four children, Obinna, 11, and daughter Chichi, 8, have sickle cell disease. Both have been racked with painful incidents over the past five years, a couple that have brought them near death.

*

Obinna and his sister have been lucky. In 1990, at age 6, Obinna suffered his first stroke, a minor one. Within the next six months he had four mini-strokes; the last one almost killed him. He spent a year in rehabilitation relearning how to walk and speak and now has limited use of his left arm and a slight limp in his left leg.

Because of his stroke, Obinna is in a special class for health-impaired students where he catches up on missed lessons. He also takes classes with his regular fifth-grade class.

His sister, Chichi, has had an equally tough time. At least every year since she was 1 she has been in and out of the hospital and has missed most of every year she has been in school. Two years ago she had hepatitis, pneumonia and osteomyelitis, a condition that literally rots the bones. She lost four inches of bone marrow in her arm, her mother said. The illness almost killed the small child.

Despite their problems, Obinna and Chichi are coping. Although he doesn’t volunteer information, Obinna doesn’t hide his disease from classmates at his elementary school. Both talk about their problems with the uncensored openness of most young children.

But that’s not the case for everyone. Even when she was small, Natasha, now 17, and her mother, Ellen, kept the fact that Natasha has sickle cell disease from everyone but a select few.

“For a while I couldn’t tell anybody,” said Ellen, 47, who asked that her name and her daughter’s be changed for this article. “I was afraid people would take it the wrong way.

“Most of (Natasha’s) friends don’t know,” Ellen said. “It’s basically always been on an as-needed basis; if you need to know, we’ll tell you.”

Natasha likes talking about the disease about as much as she likes injecting herself with the doses of Desferal she takes three times a week to counteract a side effect of her monthly blood transfusions. The medication and blood transfusions reduce the number of crises and visits to hospital emergency rooms, but after three years, her mother now has to devise tactics to get her daughter to take the medication: She restricts TV and other privileges if Natasha resists and also entreats Natasha’s closest friends to encourage her to take her medicine.

Marc Hull dreads emergency-room visits. Even though he’s screaming or crying from pain, there are times when doctors and nurses think he’s faking. It’s no different for other teens, like Hull, who have sickle cell disease but otherwise look healthy.

“People are less suspicious of a child who needs morphine than a teen-ager who looks you dead in the eye and says ‘I hurt. I need morphine,’ ” said Adrienne Bell-Cors, head of the parent support group for the Sickle Cell Disease Research Foundation.

“Being a teen, I think, is the most difficult stage in life anyway, and then to compound it with this,” said Bell-Cors, whose daughter, Marisa, 17, has sickle cell disease. “And there aren’t too many people who are sympathetic to that.”

The fallout for teens is mostly developmental. When most of their peers are beginning to test themselves as adults, teen-agers with sickle cell are confined by the tight boundaries the disease draws around them. When others can go without, they must wear warm clothing to maintain an even body temperature and flow of blood. They must shun cold climates or high-altitude environments. Too much physical exertion and any kind of stress can also affect the flow of blood and trigger a crisis.

*

The conditions narrow their choices for colleges to areas where the climate suits the disease. Even a school on a quarter system presents an added danger over schools on a semester schedule because of the increased number of stressful mid-term and final tests. And as they grow older and leave home, they have to take on the role their parents have held and become experts on their own condition and advocates for their care.

That change is hard on the parents too, said Vavasseur.

“For years, you’ve had these people running to the hospital, the schools, wherever they had to be for their kids,” she said. “They’ve been overprotective to guard them from any harm and any crises, and now bam! The kids are grown and ready to go off on their own, and the parents are scared.”

There’s a spectrum of issues for parents: They must deal with guilt for passing on the genetic disorder; they must go to extraordinary lengths to protect their children; they must cope with feelings of helplessness in the face of their child’s pain and the fear that their children will either grow old with the pain or die young.

“You never get over feeling guilty as a parent,” Bell-Cors said. “I wanted this child so much and then I have her and there’s this genetic illness that I’ve passed on to her.”

“Sometimes you think about this,” Ekwunife said, motioning toward Obinna, who was lying in a hospital bed watching television, a small IV tube carrying blood into his body. “You think maybe you did something extra bad for this to happen to you.

“But then you look at these kids and when they are not in pain they are happy and laughing and beautiful children. And that gets you through another day.”

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

WHAT TO KNOW ABOUT SICKLE CELL

Sickle cell disease is an inherited disorder of red blood cells. In sickle cell disease, red blood cells contain sickle hemoglobin, which causes them to change to a curved shape after oxygen is released. Sickled cells become stuck and form plugs in small blood vessels, blocking the flow of blood. This can damage tissue in any part of the body.

HOW SICKLE CELL AFFECTS YOU

A) Normal red blood cells: Flow freely through blood vessels without blockage, providing oxygen to the body.

B) Sickle cells: Become stuck, blocking the flow of blood in small blood vessels, which can damage body tissue.

WHERE SICKLE CELL STRIKES

* Sickle cell disease can cause extreme pain anywhere in the body at any time. This happens when the sickled cells plug blood vessels and block the flow of blood. However, it occurs most often in the arms, hands, legs, feet and abdomen.

The most common types of sickle cell disease are: sickle cell anemia; hemoglobin SC disease and sickle betathalassemia.

YOU CAN’T CATCH SICKLE CELL

* Sickle cell disease is not infectious or contagious like tuberculosis and can’t be contracted by contact with others. It is not a sexually transmitted disease, leukemia or any form of cancer.

WHO IS AFFECTED

* About 72,000 African Americans have the disease, according to the World Health Organization. An estimated 2,000 people in Los Angeles have it, the majority of whom are African American. One in every 12 African Americans in Los Angeles carries the genetic trait.

About 1 out of 185 Latinos in California have the genetic trait. Sickle cell trait and the disease do show up in whites, although the numbers are minimal, experts say.

Sickle cell disease is found in large parts of Africa as well as in the Caribbean, Central America and parts of South America, Turkey, Greece, Italy, the Middle East and the East Indies.

The life expectancy of those afflicted with the disease is 25 to 30 years shorter than those without.

SICKLE CELL TRAIT VS. SICKLE CELL DISEASE

* People with sickle cell trait do not have and will not get sickle cell disease, but they can pass it on to their children if their partner also has sickle cell trait or has sickle cell disease. The possibilities for a baby’s hemoglobin depending on the parents’ traits are shown below:

(Key)

AA - Normal hemoglobin

AS - Sickle cell trait

SS - Sickle cell anemia

*

1 - Parents: AA + AS

Baby’s: AA, AS, AA, AS

2 - Parents: AA + SS

Baby’s: AS, AS, AS, AS

3 - Parents: AS + AS

Baby’s: AA, AS, AS, SS

4 - Parents: AS + SS

Baby’s: AS, AS, SS, SS

5 - Parents: SS + SS

Baby’s: SS (All babies will be SS)

6 - Parents: AA + AA

Baby’s: AA (All babies will be AA)

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

Where to Find Help

* Sickle Cell Disease Research Foundation

4401 Crenshaw Blvd., Suite 208

Los Angeles, Calif. 90043

(213) 299-3600

(This center has nine satellite offices throughout Los Angeles, Long Beach, the San Fernando Valley and Santa Barbara.)

* King-Drew Sickle Cell Center

12021 Wilmington Blvd.

Los Angeles, Calif. 90059

(310) 668-3164 or (310) 668-3167

* Sickle Cell Anemia Education & Detection Center

Lynwood

(310) 636-6296

* National Assn. for

Sickle Cell Disease

3345 Wilshire Blvd., Suite 1106

Los Angeles, Calif. 90010-1880

1 (800) 421-8453

* California State Dept.

of Health

Children’s Medical Services

Sacramento, Calif. 95814

(916) 654-0499

* IN VOICES

Camille McTeer Noldon talks about her struggle with sickle cell disease, and her decision not to let it control her life. Page 18

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.