The Other Victims : Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman were not the only ones murdered on June 12. But we don’t think about the four others--or the families left wondering if justice can ever be done.

- Share via

We see the day--June 12, 1994--through many eyes: a housekeeper named Rosa, a sister named Denise, an actor and a dog, both known as Kato. The mysterious, diminutive pieces of a fateful puzzle are shuffled and framed, and what emerges are contrasting pictures of what happened that day on Bundy Drive.

Typically, about five homicides are reported to the Los Angeles County coroner’s office on any given day--1,798 in 1994.

June 12 was remarkable not for the six homicides that were reported, but for the identities of the day’s final two victims--Nicole Brown Simpson and Ronald Goldman--as well as the man who has been charged with killing them--O.J. Simpson.

We are reminded of the day in terms of burning candles, melting ice cream and a dog’s plaintive wail. We do not think about the four other victims.

We do not think about Jaime Apolonio Moreno, a 26-year-old father of two. June 12 was not only the day Gloria Monroe lost her first son, it was the day she lost her faith in God.

Each time she hears about the money being spent in the Simpson case, her heart breaks a little more. If she had been richer, she wonders, would the case have turned out differently? No one was charged. We do not think about Cynthia Margaret Siegfried, 30. Her body was laid to rest in an unmarked grave at the back of a cemetery near warehouses. The family could afford no more.

She left behind two children who were the source of her strength. They were the reason she was trying desperately to change the course of her life, but a stray bullet cut her down in mid-turn. A man pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter.

We do not think about David Wayne Abraham, 29, father of a young son. Abraham worked with developmentally disabled children, who would listen to him when they would listen to no one else. Abraham, of Rialto, died of multiple gunshot wounds, and his body was found dumped in the middle of a Los Angeles street. There has been no arrest.

And we do not think about Trinidad Velasquez, 27, who police suspect was fatally shot by her husband during an argument in their Monrovia home. By the time police arrived, he had fled; his 1980 Pontiac Firebird was found in Azusa the following day, according to police.

Millions of dollars have not been spent to find justice for the families of Moreno, Siegfried, Abraham and Velasquez. Juries have not heard their cases, and the media have not shown the world their tears.

Instead, they have been left believing that justice belongs not to them, but to the rich and famous.

For them, it was not ice cream and candles that began melting away on June 12. It was faith in justice.

*

Vickie Moreno kneels next to the headstone of her husband’s grave. She has brought flowers, two children and lingering hope that peace might someday return to her heart.

The heaviest weight she carries--more crushing than sorrow or fear--is that of guilt. Others have said, in whispers or screams, that it is because of her that Jaime is dead. And in her darkest moments she, too, blames herself.

“I feel responsible. It was because of me,” she says. “It’s always because of me.”

Her son, 7, and daughter, 3, know the routine, for they have been here many times since June 12. Vickie, 28, pours water on the marker, then her son rubs at the cool stone surface with a towel until it clearly reflects his father’s name.

The children arrange flowers on the marker, settling for a pink carnation in one top corner of the stone, a red one in the other. A red ribbon is placed in the center.

June 11 had been a day of celebration, the irony of so many tragedies. Following a baptism, Jaime and Vickie were celebrating at her parents’ home near Huntington Park. There was music and dancing throughout the day and into the night. Jaime, who managed the family business, C & M Metals, was learning to salsa.

Vickie left the party and decided to visit her sister, Paula Fernandez. Paula’s husband, Lorenzo Fernandez, had never gotten along with Vickie. After speaking briefly with Paula, Vickie says she walked toward her car to leave and heard shouting inside the house.

Vickie drove away but, concerned about her sister, returned a short time later. A fight ensued between Vickie and members of the Fernandez family.

Vickie--bruised and scratched--left, vowing to return. She drove to her parents’ house and got Jaime.

According to Deputy Dist. Atty. John Lynch, Jaime was stabbed by his brother-in-law with a kitchen knife while trying to force his way into the Fernandez home, a fact Vickie now disputes.

Lynch says people inside the home--who had made numerous calls to 911 that morning--had reasonable cause to fear for their lives, and deadly force was, therefore, justified even though Jaime Moreno was unarmed. Fernandez was not charged.

Friends and family paint a saintly picture of Moreno, nephew of former Chicago White Sox outfielder Darrin Jackson, now playing in Japan. They show him in photographs, always smiling, and in memories, always helping others.

He was an overprotective father who did much of the cooking and cleaning at home, helping his son with homework, getting the children ready for bed. Each morning, he was the first to arrive and the last to leave C & M Metals, owned by his grandfather. He had worked there with his mother since age 12 and planned to take over the business someday.

More than 1,000 people signed a petition submitted to the district attorney’s office urging that murder charges be filed.

In a letter written to Yvonne Brathwaite Burke of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors, Allen J. Berliner, a friend of the family, wrote: “I hope that our Sheriff’s Department treats this murder as it would the recent murder of O.J. Simpson’s wife. I know this will never happen, but an effortless response will only send the message that murder within some segments of our society is to be tolerated. . . .”

Moreno’s father, Don Monroe, says he feels guilty for his son’s death, for having taught him to survive in a world more peaceful than this one has become.

“All my kids were taught to look for the good in people. . . . We have not taught them that in order to survive, you have to look for the dark side of the other person. It’s all right to have love for people, to have respect for people, but unfortunately, I have learned that there’s a time to kill.”

A part of Gloria Monroe died with her son. The family no longer celebrates birthdays. No lights were strung at Christmas. There no longer seems reason, she says, to celebrate.

“My son’s life goes like that and nobody does anything because I’m poor, because I don’t have money, so my son’s life isn’t worth anything. My son, he was not trash. He was a good person, a good citizen, a good man.”

Vickie Moreno, who works in the human resources/payroll department for a furniture manufacturing company and attends night school, says that since the incident, she hasn’t talked to her sister, Paula Fernandez. It has torn her family apart, and sometimes she feels caught in the middle.

“I still love her, but when I think about her I feel guilty, like I should no longer love her because of what happened to Jaime, but she’s my sister, you know?”

Each weekend, she visits Moreno’s grave at the Holy Cross Cemetery in Culver City.

In the back of the cemetery, in Section X, is the grave of another person who was killed June 12--Cynthia Siegfried.

*

Since her daughter’s death, Martha Siegfried has been afraid to sleep, because that’s when she sees Cynthia. The Torrance woman spends most nights sitting next to the window in the kitchen beneath a simply framed painting of the Last Supper, occasionally resting her head on the small table.

“I sleep in the chair,” she says. “I keep sitting up thinking, you know, she’s going to come home, but I have to realize she’s not going to come no more. I have to keep thinking that way, but I don’t know how.”

Martha Siegfried has not been the same since the incident, says her other daughter, Donna Eastep, 32, of Reno. “People say I sound just like Cindy,” Eastep says. “Our voices are the same, and since Cindy was killed Mom calls me all the time, but I think it’s to hear Cindy’s voice.”

It was a life in late bloom, Eastep says. Cynthia Siegfried was on the mend from alcohol and drug abuse. It wasn’t until her two young children were taken from her and placed in foster homes a year and a half ago that she realized she had to change her life.

Siegfried was being tested regularly for drug use and had completed parenting classes. She had worked as a temp and was in a job-training program. She started attending church and reading books about religion. A new person was beginning to emerge, and at the center of that new life was a mother’s love for her children, Eastep says.

Late on the night of June 11, Siegfried was visiting a friend, Shirley Knocke. They were going to the store, but Knocke decided to stop and see her estranged husband, Michael Knocke, in Lomita at about 1:30 Sunday morning.

Michael was standing outside when they pulled up, Knocke says. She and Michael argued briefly, then he went into the house. She began to drive away when she saw him reappear with a rifle.

She says she stopped, got out of the car and walked toward him to get him to put down the rifle. They argued more, and he turned away from her and fired into the air. Knocke says she grabbed for the rifle, and two more shots went off by accident, one of them striking Siegfried in the chest as she was waiting in the car.

Michael Knocke pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter; with Strike 2 time added for a previous robbery conviction, he was sentenced to 17 years in prison.

The family had no money to bury Siegfried.

“She was laying in the morgue, and we didn’t know where we were going to put her,” Eastep says. “We had to buy the cheapest coffin we could find. That hurt a lot.”

Still, Martha Siegfried, 54, says she shares the pain of the victims’ families in the Simpson double-murder case. “I know how they feel, even though they got money,” she says. “You can’t buy love, you can’t buy back a life.”

The day after the shooting, Martha went to the scene of her daughter’s death. She saw the dry circle of blood on the street, walked toward it and stood upon it. It was the beginning of saying goodby, a painful process that continues.

*

Less than three hours into June 12, the county’s third murder was reported. David Abraham, 29, left behind a 28-year-old wife and a 3-year-old son. He worked with developmentally disabled children and had formed his own business--managing and promoting music groups. He was shot and found dead in a street in the Crenshaw District. No arrest has been made.

“Just another dead black man. That how it makes us feel,” says Abraham’s aunt, Connie Redder, of Irvine.

His wife, Phyllis Abraham, says that because of the circumstances of his death, David was immediately thrown into the category of drug dealers and gang violence.

“Nothing could be further from the truth,” says Detective Chuck Tizano, an 18-year veteran of the Police Department who is handling the case. “It was obvious to us right away that he was not involved with gangs or drugs. We believed he was a victim of robbery or a car-jacking.”

Gil Freitag, director of the Dubnoff Center, described Abraham as a dedicated worker. The night before he was killed, he had stayed late to fill in for a co-worker and to finish paperwork.

“David always wanted the best for our kids,” Freitag says. “We’re a nonprofit organization and when we take kids on field trips or things like that, our budget doesn’t really allow for the best accommodations, but David would insist. He would advocate that they should have nothing less than the best, and for the most part, he succeeded.”

Sometimes giving the children what they wanted required extra effort. The girls in the group home he supervised wanted to wear their hair in braids for a school dance, but none of the staff members knew how to do it. Abraham went out and learned, then braided their hair so they would not be disappointed.

Following Abraham’s death, about $5,000 in stolen checks started passing through his bank. Redder doggedly conducted her own investigation, making telephone calls to stores to uncover details that might help find the killer. One store gave her a description and car license number of one of the check-writers, who had purchased a television.

“I gave all that information to the police but never heard back from them,” she says. “Throughout all this, we have heard almost nothing from the police.”

Tizano says the plates were traced to a previous owner of the vehicle who did not know who the current owner was. The checks, he said, were investigated but couldn’t be tied to the homicide.

Phyllis Abraham says she has little hope for an arrest. “I still want them to catch whoever killed my husband,” she says. “I wouldn’t want anyone else to have to go through what I’m going through now.”

The Simpson trial only adds to their pain.

“I watch a little of the trial, but I try not to,” says Redder, who has meticulously recorded details of Abraham’s death, just as she did eight years ago when her sister died, four years ago when her father died, and eight months ago when her mother died.

She is frustrated about the lack of progress in her nephew’s case, especially in light of the resources utilized in the Simpson case.

“It’s upsetting, because you think about your loss and how nobody cares about your loss, your pain, your feelings. I had someone die on that same day. I had someone killed. Did it matter to anybody? No. . . . We’re hurting. We lost someone we loved just as much as those people loved theirs. You can’t measure love. It doesn’t matter if you’re rich or famous, you hurt and you love, but we’re just lost. We’re just little people.”

*

Little is known about the day’s fourth murder victim, Trinidad Flores Velasquez. She was believed to have been fatally shot by her husband, Zenaido Gutierrez, in their Monrovia home, according to L.A. County Sheriff’s Deputy Michael Crowley.

“We believe he ended up battering her around and ended up in the bedroom, where he took a gun out and confronted her. She didn’t feel he was going to use it, so she didn’t back down; but he did,” said Crowley, an investigator on the case.

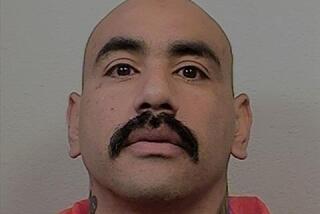

The call came in at 3:35 p.m., and by the time sheriff’s deputies arrived, Gutierrez had fled. Velasquez was shot several times with a .25-caliber automatic, Crowley says. Gutierrez, 20, is described by police as being about 5-feet, 3 inches tall, 140 pounds, with brown hair and brown eyes.

*

The Velasquez murder was followed by a period of calm, an uneventful Sunday afternoon in June. The temperature hit 75 degrees Downtown. The Dodgers beat the Cubs. “Speed” led at the box office, overtaking “The Flintstones.”

Late that night, the number of homicides hit six.

It was a typical day in L.A. County.

(BEGIN TEXT OF INFOBOX / INFOGRAPHIC)

The Other Victims

* Jaime Apolonio Moreno, 26, Los Angeles: Stabbed by brother-in-law. Ruled justifiable homicide.

* Cynthia Margaret Siegfried, 30, Torrance: Shot by stray bullet. Defendant pleaded guilty to voluntary manslaughter.

* David Wayne Abraham, 29, Rialto: Multiple gunshot wounds. No arrest.

* Trinidad Flores Velasquez, 27, Monrovia (not pictured): Gunshot wounds. No arrest.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.