JAZZ REVIEW : On Guitar, Brown and His Invisible Partner

- Share via

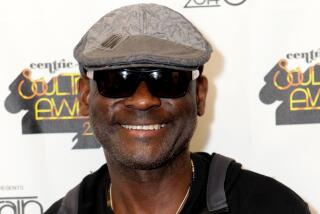

NEWPORT BEACH — Norman Brown borrowed a lot from fellow guitarist George Benson when he played the Hyatt Newporter on Friday.

Brown most resembled the big-selling Benson as he scatted in unison with his own guitar licks, the same technique that drove Benson to stardom. He also sounded a tonal quality similar to Benson’s and played two-note unisons an octave apart, a technique that Brown’s trend-setting predecessor picked up from the late Wes Montgomery.

But Brown’s way of attacking a song could hardly be described as “Breezin’,” the title of Benson’s breakthrough hit of the ‘70s. Instead, the younger guitarist brought an intensity to everything he presented--whether playing his own tunes or covering numbers from Stevie Wonder, Janet Jackson and Marvin Gaye--packing each piece with blistering, single-note runs and chordal passages that made Benson’s somewhat laid-back approach look tired by comparison.

Not only did Brown’s solos spit and steam, they told a story, carrying a lyricism that belied the frenzy of his presentation. Even the most accessible and direct material, such as Brown’s “After the Storm,” reverberated with strength and string-picked excitement as he moved into improvisational mode.

This sort of aggressive play made Brown’s blase material palpable, even after one had grown tired of the predictable backbeat and pop themes. If only he had included just a handful of more involved numbers, say John Coltrane’s “Giant Steps” or even Wonder’s “For Once in My Life,” the effort would have gone a long way toward legitimizing his voice and bringing him out of Benson’s shadow.

Instead, Brown stuck to heartbeat, four-count rhythms and easy thematic material too much of the time. Exceptions, such as Wonder’s “Too High” and Brown’s own “Lydian,” stood out like beacons, illuminating the guitarist’s considerable skills in a way that the simpler pop-based material could not.

Even the blandest of tunes were presented in tight and energetic fashion by Brown’s backing quartet under the direction of keyboardist Gail Johnson. At the core of the sound was bassist James Manning and drummer Alonzo (Scooter) Powell, who kept Brown’s rhythm train on track. Manning was especially adept at keeping the songs supported, content to play the bottom straight and without unnecessary embellishment. Powell’s play featured a heavy reliance on the snare drum, a ploy that gave his sound a toothy snap.

The dual keyboards of Johnson and Charles Love were layered so quietly into the sonic mix that they went largely unnoticed during ensemble play. Love’s only moment in the spotlight came near the close of the show as he took a synthesizer solo that brought a breath of harmonic freshness to the proceedings.

Brown’s vocals, whether put to lyrics or in wordless syllables sung in unison with his guitar, do little to distinguish him from Benson. His weakest vocal moments came on the last tune, Gaye’s “What’s Goin’ On,” in which his voice became just an embellishment to the strong instrumental presentation. The one facet of his delivery that Brown could use to separate himself from Benson is his voice. Sadly, it’s the thing that most recalls him. At any number of times during the show, Brown could have broken into “On Broadway,” Benson’s most recognizable number, and no one would have batted an eye.

Also on the bill was saxophonist Jeff Gonzales, reviewed here in June during his performance at the Dana Point Jazz Festival and who has added bassist John Heart to the trio. The move beefed up his program of soft rockers and funk tunes.

The soprano man made his best showing on the Miles Davis-Marcus Miller collaboration “Splatch,” maneuvering the hip-hop-flavored exercise with abandon and rhythmic authority.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.