CLOSE-UP : That Sinking Feeling

- Share via

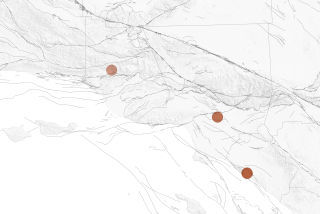

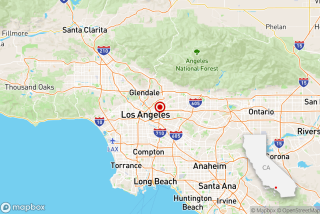

It’s gargantuan. Bigger than any mountain. It’s long. Longer than any L.A. riveror street. It’s rare. Fewer than a dozen have been found anywhere on the globe, and of those discovered, none is as shapely as ours. No one has ever seen it with the naked eye, and geophysicists haven’t named it yet, but they know its size and location. It hangs below the northern end of the Los Angeles basin under the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains like a giant ship’s keel.

Only it would be a ship of gods, because the keel is a fantastic 150 miles deep and consists of cooler rock penetrating the taffy-soft green and black rock of the earth’s hot interior.

“When I saw it down there, I didn’t know what it was,” says Eugene Humphreys, a geophysicist at the University of Orgeon who was one of the first to generate a computer image of it in the early ‘80s. He created an image of the keel by examining earthquake waves, which travel at speeds that vary with the temperature and density of the rock. These seismic waves allow geophysicists to make a “CAT scan” of the earth’s interior.

Humphreys now thinks that the keel is hard mantle rock that’s sinking below the crust. “As a heavy sinker, it sucks the crust above it together, creating the San Gabriel and San Bernardino mountains.”

He also believes that the keel has created the “big bend” in the 600-mile-long San Andreas fault, where the fault bends in a more east-westerly direction just north of the San Gabriels. “The San Andreas is where it is because of this feature,” he says, “and the bend in the San Andreas gives rise to the mountains,so it’s all related.”

Not all geophysicists agree with Humphreys. Some argue that the keel could be the northern end of the Baja peninsula--crust and all--sliding under our mountains. Whatever it is, the thing is only sinking two inches per year at most, and has been doing so for a comforting four to 10 million years.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.