The Mother of All Outrages: Bonin on Social Security

- Share via

Do they allow laughing in hell?

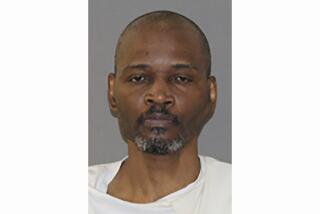

If so, William Bonin no doubt is yukking it up. Sure, the state of California slipped him a lethal injection a couple weeks ago, which normally would sour relations between a person and the government. But as if to show there were no hard feelings, the Social Security Administration has acknowledged it never ended Bonin’s monthly disability payments during his 14 years in prison.

The safety net doesn’t get any wider than that.

The result of what the government is calling a screw-up is that a bank account shared by Bonin and his mother received $79,424 over the years. Obviously, Bonin couldn’t get to it, but his mother could, and did.

She told a newspaper that she had used the disability payments to pay off the family house in Downey.

You would think that at some point in the last 14 years, she might have felt a pang of conscience about building a nest egg off her son’s disability check.

Disability, indeed. Bonin, 49 when executed last month, qualified for the benefits after being diagnosed in 1972--several years before his murder spree began--with a mental condition. According to federal law, the benefits were supposed to stop when he went to prison.

For reasons unknown at this point, they didn’t.

While Bonin was establishing himself as the “Freeway Killer” and all the way through his trial and subsequent life on death row, he was socking it away.

Now, you might argue, “Hey, it’s not his mother’s fault. Why should she ask about the money? If they want to give it to her, why should she complain?”

This is not exactly the same as getting HBO for free without the cable company knowing about it. Most people might feel sheepish about that but still not blow the whistle on themselves.

But let’s say your son had confessed to 21 murders and wreaked devastating pain and suffering on victims and their families and friends. Wouldn’t you feel a twinge of guilt over fattening your bank account with his government checks? Wouldn’t you at least make a phone call to someone, or have someone do it for you, to check on the legality or, at least, the propriety?

Of course, we ask too much of some people.

The Bonin household was never the center of propriety. Court records indicate that his father was a violent alcoholic and chronic gambler. Both mom and dad left Bonin and his brother alone for long periods, and Mrs. Bonin--now Alice Benton--was beaten often by her husband, according to court filings. Those reports also say that Bonin’s mother kicked him out of the house when he was young. By age 8, he had already been to an orphanage and a detention center.

Back home in Downey as an adult, Bonin began attracting neighbors’ attention with his behavior. They would later tell of hearing frightened screams coming from the house and then of rumors that Bonin had bought beer and showed X-rated movies to neighborhood boys. One neighbor remembers an adult Bonin coming back home with a young boy, while his mother and the neighbor were playing cards.

Everything about the Bonin story reeks of misery and horror. One way a lot of Southern Californians came to grips with that was to derive a sense of vengeance from his execution.

This guy, he was something, though. Even when they executed him, he was still getting away with murder.

As for his family, it agreed this week to repay the benefits that were received illegally. Terms of the settlement were not disclosed because of privacy restrictions.

But Shirley S. Chater, Social Security commissioner, and David C. Williams, the agency’s inspector general, said in a statement that criminals such as Bonin must be kept “from committing a second crime against the taxpayer.”

Bonin’s mother has said very little. Bonin’s attorneys often pointed to his great love for his mother. Maybe it doesn’t bother her that she paid off the house from his Social Security.

We’re reminded that William Bonin, right up to the end, expressed no remorse for his deeds.

He had to pick up the trait somewhere.

Dana Parsons’ columns appears Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. Readers may reach Parsons by writing to him at the Times Orange County Edition, 1375 Sunflower Ave., Costa Mesa, CA 92626, or calling (714) 966-7821.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.