Blacks’ Admiration for Brown Heightens Their Sense of Loss

- Share via

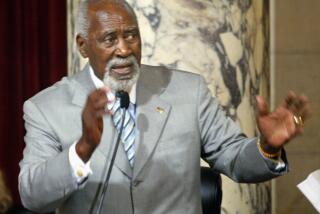

WASHINGTON — Just as African American stars Michael Jordan and Michael Jackson earned acclaim well beyond black audiences, Commerce Secretary Ronald H. Brown won international respect and success--but he took a more difficult route.

Unlike celebrated athletes or entertainers, Brown, who died in a plane crash Wednesday during a trade mission in Bosnia, made his mark in the mainstream of American politics and business, which is difficult for even the most talented black Americans.

That made his achievement special among black Americans, particularly within its middle class. And it magnifies the sense of loss because Brown stood as an inspiration in a way that athletes and performers rarely do.

“He demonstrated that, given an opportunity, African Americans can succeed and can make an overall impact,” said John Mack, president of the Los Angeles chapter of the National Urban League. “We can have heroes and heroines in areas other than athletics and entertainment.”

Interviews with dozens of blacks--who knew him or only knew of him--reveal an admiration for the ability of the man who grew up in Harlem to move easily from the rarefied atmosphere of the White House to inner-city basketball courts, from rainmaker at a major Washington law firm to grass-roots organizer for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential campaign--apparently with the same charm, optimism and dimpled smile for each audience.

“He was a black man who defined his game, played it and won big,” said P. Louise Shaw, a political consultant in Baltimore. “He did that without compromising his African American perspective and sense of community empowerment.”

For some black employees within the Commerce Department, grief over his death is mixed with fear that the loss of his political skill and activism on their behalf makes their jobs less secure.

One senior-level Commerce Department official, who is black and asked not to be identified, seemed to be describing the general feeling of loss shared among black workers in the federal department.

“We’ve lost our leader,” the official said. “This place was as white as the snow before he came and I fear it’s going to go back that way now that he’s gone. Don’t get me wrong. I feel for the brother and his family at this time. But I also feel for all the brothers and sisters who, like me, came to work at Commerce because of one man--Ron Brown.”

Marsha Bishop, a secretary in the administrative office at Commerce, said that Brown “was different” from others she had witnessed in ranking Cabinet positions. “He was an ordinary black man, who was looking out for all of us,” she said. “He wasn’t someone you felt was untouchable, like a lot of our folks who have big jobs and fancy titles. I respected that about him more than anything else.”

Earlier in his professional career, Brown had served 12 years in various executive roles with the National Urban League. He later was the first black chief counsel to the Senate Judiciary Committee, a partner in the Washington law firm of Patton, Boggs & Blow and chairman of the Democratic National Committee, where he helped engineer Clinton’s 1992 presidential victory.

As Jesse Jackson and other admirers describe it, Brown benefited from having both the “ability and opportunity” to demonstrate his political skills in black and white environments.

“He was not about to be marginalized as just a black leader,” said Jackson. “When he was head of the DNC and had to raise money for white Democrats, they couldn’t say he was [just] a black leader. When he was appointed secretary of Commerce and had to go to Bosnia or another setting, where he had to represent all the people of the United States, no one could marginalize him as the black Cabinet secretary.”

Jackson said that other black political leaders have been less successful at establishing themselves with the white majority America because of “resistance on the part of white Americans” to view black people outside the boundaries of tradition.

“But Ron Brown was not going to settle for a traditional position in America,” Jackson said. He said that Brown demanded and received his job as Commerce secretary in the Clinton administration because he wanted a position that no black person had ever held before.

A generation of blacks in public service owe their love of politics--as well as their jobs--to Brown, said Rep. John Lewis (R-Ga.). He noted that many of the young blacks employed at the Democratic National Committee and on Capitol Hill were attracted to Washington and public service by Brown’s example.

“He included people,” Lewis said. “He tried to bring young African Americans and women up whether at the DNC or the Urban League or as secretary of Commerce.”

In return, Lewis added, his followers “worshiped him . . . [because] he was urbane, sophisticated but, at the same time, just plain down to earth.”

Lewis said he believes that the key to Brown’s ability to straddle diverse communities stemmed from his childhood in Harlem and the fact that his family lived through the 1940s and ‘50s at the Hotel Theresa, a cultural crossroad where successful black Americans mingled with the poorer black community.

“He saw people at different levels in the black community and the white community,” Lewis said. “He saw African Americans doing well and others not doing so well. And he was able because of his history and background to relate to both communities.”

Mack said that the ability to relate to different groups of people earned him respect and confidence among world leaders, especially those from developing nations.

“They were aware that he had more sensitivities to their culture and traditions than many American diplomats,” he said. “Third World leaders had a tremendous respect for him because he was African American. He related to them whether they were sheiks from Saudi Arabia or leaders from Africa or Asia.”

Jackson said he benefited from Brown’s political skills during his unsuccessful 1984 and 1988 presidential campaigns. In 1984, Brown served as the campaign’s national director. In 1988, Brown declined a formal role but served as a broker at the Democratic National Convention to smooth relations between Jackson and the nominee, former Massachusetts Gov. Michael S. Dukakis.

“He was comfortable and successful in that role,” Jackson said. “Ron knew how to walk between cultures and different groups. That was his gift.”

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.