GREAT ESCAPIST

- Share via

John Sturges hated what television did to his movies. He especially hated what pan-and-scan cropping did to his Panavision classics, such macho primers as “Bad Day at Black Rock” and “The Magnificent Seven.”

Looking at a letterbox laserdisc version of “Black Rock” a few months before he died in 1992, Sturges grumbled, “Pan-and-scan? It drives me nuts. All those weird moves to include whoever’s talking.”

Hardly what you’d call a sentimentalist, even in his final days, it’s hard to believe Sturges wouldn’t be pleased by the letterbox edition of his 1963 hit, “The Great Escape.” Thanks to MGM/UA’s Screen Epics series, VCR owners finally can see the POW classic in all its widescreen glory. (“The Great Escape” has been available for $89.95 from Voyager’s Criterion Collection; MGM/UA’s two-cassette version is a more affordable $24.98.)

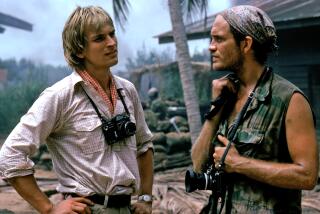

Especially impressive in the full Panavision format are the establishing shots of the German prison camp (built outside Munich), the seamless tracking shots of Charles Bronson burrowing to freedom and, of course, Steve McQueen’s sprint across the Bavarian countryside on a commandeered motorcycle.

With the entire picture back on screen, it’s easy to understand why Sturges considered the World War II adventure one of his best efforts. Boomers who discovered the three-hour epic as teenagers (and this includes Steven Spielberg) rightly place it beside David Lean’s “The Bridge on the River Kwai.”

“It’s amazing how ‘The Great Escape’ and ‘Magnificent Seven’ [1960, also with McQueen] are enjoying a renaissance,” the 82-year-old producer-director said in his final interview at his hillside home in San Luis Obispo. “There’s a whole new generation that’s discovering my pictures. I earned $140,000 just last year on video and laser sales because I own, with United Artists, those two films.

“That should tell you something right there: There are not too many films being made today that are that kind of large-scale, big-emotion picture.”

Indeed, budgeted at $3.2 million (or roughly $20 million by inflated ‘90s standards), “The Great Escape” almost didn’t get made. It was deemed too costly, too complicated and--here’s a surprise--too downbeat.

“When I said I wanted to make ‘The Great Escape,’ they thought I was crazy. They said, ‘What kind of escape is this? Nobody gets away.’ ”

Taken from Paul Brickhill’s account of the largest coordinated breakout in military history, Sturges’ film chronicles a mass escape in 1943 from Stalag Luft North, designed to discourage incorrigible moles. Richard Attenborough, James Coburn, James Garner, David McCallum, Donald Pleasence, Bronson and McQueen are among the international actors who tunnel out of the compound. In all, 76 men escape. Fifty are executed by the Gestapo, three make it to freedom and the remainder are returned to prison.

Sturges and co-screenwriter James Clavell (a real-life POW) knew the numbers were immaterial; their story was a rugged, if highly theatrical, metaphor for the kind of we’re-all-in-it-together cooperation that won the war.

“ ‘The Great Escape’ was not just an action movie,” Sturges stressed. “It’s this story of these different nationalities who form an organization to wipe out the Nazis. It’s about this uncontrolled, do-it-your-way form of life--our way of life--defeating these dictatorial sons of bitches OK? with their armies.”

Though justifiably proud of the big action sequences, such as the climactic motorcycle jumps (done by McQueen’s stunt double, not McQueen, as Hollywood lore would have it), Sturges favored the quieter interludes. “The scenes that make it work are like when Blythe [Pleasence] realizes he can’t see and he plants a pin to try to convince Hendley [Garner] that he can; and the quarrel between ‘Big X’ [Attenborough] and Hendley over playing God, deciding who goes and who stays. That’s what makes the picture work. It’s the emotional involvement.”

Coming off his biggest hit--”The Magnificent Seven” (the Western version of Kurosawa’s “Seven Samurai”)--Sturges, in 1961, could have gotten the Burbank phone directory green-lighted. “You get your way when you’re a winner,” he said. (“By Love Possessed” and “A Girl Named Tamiko,” two ill-advised detours into turgid romance, were mercifully overlooked.)

On location outside Munich, cast and crew were beset by problems, ranging from bad weather to angry conservationists (who insisted all trees removed for the stockade be saved and replanted) to McQueen’s insecurity. Intimidated by his mostly stage-trained co-stars and later diagnosed as dyslexic, McQueen felt his role as the baseball-tossing Cooler King wasn’t meaty enough. Things deteriorated quickly until Sturges--a lanky veteran with an Oscar nomination and more than 30 films to his credit--handed the actor his walking papers.

Of course all hell broke loose--and McQueen’s representatives from the William Morris Agency flew in to handle damage control.

“I got so mad I took him off the picture and shot around him,” Sturges recalled during that final interview. “Steve kept getting upset because everybody was something--Sedgwick was ‘The Manufacturer,’ Hendley was ‘The Scrounger,’ etc. I couldn’t get him to realize the part he was playing was the loner. I told him, ‘You don’t want to be a member of the crowd.’ But he couldn’t get it. Finally I said, ‘Steve, if you don’t believe the scenes, you’re going to be lousy. And frankly I’m tired of arguing with you. So if you don’t like this part, to hell with it. We’ll pay you off.’ ”

Five days later, a contrite McQueen--no doubt reminded of how indebted he was to Sturges for his first career breaks--was back in harness, very much the team player.

Though it runs almost three hours, “The Great Escape” was considerably longer in its first previews in Santa Monica. Sturges cut about 10 minutes of comedy relief--scenes involving the prisoners’ potato whiskey and Sedgwick’s mystery suitcase (which, preview audiences learned, contained wine, cheese and a book). There were no second thoughts about the trims, and a reassembled director’s cut, a la “Spartacus” and “Lawrence of Arabia,” was never contemplated.

Sadly, after “The Great Escape,” Sturges’ movies got bigger and more impersonal. He blamed his own ego and bad script choices. Among the pet projects that never came together: “Richard, Sahib” (a Clavell script meant for Spencer Tracy and Alec Guinness), “The Yards of Essendorf” (a young Warren Beatty as a Yank caught behind enemy lines) and a “Great Escape” sequel called “The Artful Dodger.” The movies that did get made--”Ice Station Zebra,” “Marooned” and “McQ,” with John Wayne--probably shouldn’t have. They came off as inadvertent lampoons of the director’s stock-in-trade.

After the amazingly tasteless western spoof “Hallelujah Trail” (1965) with Burt Lancaster, Sturges said he “couldn’t sell the proverbial ice cubes to Eskimos.”

He should have kept to what he knew. “My bag was always gallantry--the kind of thing you see in ‘High Noon’ and ‘Shane.’ But the power and the money were addictive. They paid me $500,000--that’s $5 million today--for ‘Ice Station Zebra,’ which went into production with only a third of a script.”

Sturges at the end (diagnosed with acute anemia and emphysema) would not lay blame: “I’ve never been an alibi man. The critics were right about my later films. Some of them were pretentious; some of them made more out of the material than was there to be made. But some of them sure worked. Yes, they did. I had a flair for staging.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.