Witness Against Pratt Changes His Testimony

- Share via

SANTA ANA — A key witness against imprisoned former Black Panther Party leader Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt changed his testimony Monday, saying he had not intended to say he was an informant when he testified last week that he had once acted as one.

In response to a question from Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., one of Pratt’s lawyers, Julius C. “Julio” Butler testified last Wednesday that he was “acting as an informant” in 1969 when he took two Los Angeles police officers to a vacant lot to recover weapons abandoned by Black Panthers.

On Monday, Butler, 64, testified that he had intended to say: “No, I was not an informant” when he directed the officers to the weapons. He added that he would not dispute the officers’ belief that he was an informant.

Undermining Butler’s credibility is seen as the most important task facing Pratt’s attorneys in their effort to overturn the murder conviction that has kept their client behind bars for 26 years.

At Pratt’s original trial in 1972, defense attorneys and the jury did not know that Butler had been providing information to the FBI for 2 1/2 years before Pratt’s conviction.

Butler denied on the witness stand that he had ever been an informant, but FBI documents released in 1979 disclosed that he had more than 30 documented contacts with agents before Pratt’s trial.

Two former Los Angeles police officers have given sworn statements that Butler was their informant. Last summer, investigators from the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office discovered Butler’s name in their own file of confidential informants.

Butler, however, has insisted that he has never been an informant for any law enforcement agency. His role was that of a “liaison” between law enforcement and the Panthers, Butler said, helping to defuse potentially volatile situations. He also testified that he helped mediate disputes between Panthers, police and local merchants who felt that they were being coerced into selling the Panthers’ newspaper.

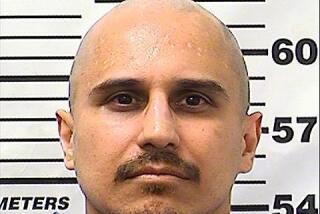

Pratt, 49, has maintained throughout his trial and in the years since that he was in Oakland when schoolteacher Caroline Olsen was shot to death and her husband, Kenneth, was critically wounded during a 1968 robbery that netted $18 on a Santa Monica tennis court.

*

Butler testified at Pratt’s murder trial that Pratt had confessed the murder to him. Pratt has denied making any such confession.

Pratt filed a request for a new trial earlier this year and was granted a hearing on evidence his lawyers say points to his innocence. That hearing was moved to Orange County to avoid a conflict of interest because Los Angeles Superior Court Judge Richard P. Kalustian, the deputy district attorney who prosecuted Pratt, was a witness.

Butler testified Monday that Pratt and two other Panthers, Roger “Blue” Lewis and John “Long John” Washington, had threatened his life sometime in August 1969.

“Mr. Pratt told Long John to shoot me,” Butler said. “Long John had a gun cocked to my head.”

Butler said he had armed friends inside and outside his apartment building, and he told the three Panthers: “You may kill me, but you won’t leave the premises alive.”

He said he quit the Panthers after that incident, but FBI reports say that he was expelled. That same month, he wrote what he has called an “insurance letter,” to be opened only if he were killed.

He turned that letter over to his then-friend, former Los Angeles Police Sgt. DuWayne Rice. In it Butler implicated Pratt in the so-called “tennis court murder”--the first time Pratt had been tied to the crime.

Butler has testified that he intended the letter’s contents to be kept secret, but two men believed to be FBI agents arrived shortly after he gave the letter to Rice. The agents demanded the letter, but Rice refused to surrender it. Months later, he turned it over to his LAPD superiors after Butler gave him permission to do so.

Pratt’s lawyers have argued for years that the letter was part of a scheme to frame Pratt, saying that the agents’ presence when it was given to Rice supports their contention. An FBI memo had instructed agents to consider ways to “neutralize” Pratt as an effective Panther leader.

Outside court, Cochran scoffed at Butler’s denials that he was an informant, noting that Butler often said he could not recall meeting FBI agents as described in memos.

“He has this real problem with memory,” Cochran said. “He admits last week that he was an informant. He comes back and says he was wrong: ‘I didn’t mean to say that.’ We’re just trying to show just how improbable he is.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.