The 3 Rs: Re-Think, Re-Imagine, Reform

- Share via

There are two ways to think of Leon Botstein’s new opus “Jefferson’s Children” this holiday season: as a gift or as required reading. For a Harvard-educated doctor who wonders how much TV her 1-year-old should watch. For a cousin out in Brooklyn who doesn’t vote. For a divorced friend who struggles daily with her dropout son. For elementary school teachers in Bayonne, N.J., Milwaukee, Wis., and Montgomery, Ala., who are fighting for the basic right to give children a quality education. “Jefferson’s Children” should be on the holiday syllabus for parents, grandparents and anyone who wonders why everything they’ve learned since kindergarten is such a blur.

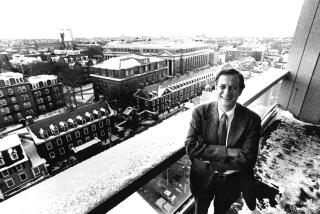

Botstein is a Renaissance man: the president of Bard College and musical director of the American Symphony Orchestra. But he is also an Enlightenment thinker in the tradition of David Hume, with a staunch faith in the ability of education to create a more democratic citizenry. While acknowledging that education may not be sufficient for the establishment of a better society (Nazi PhD’s being just one example), Botstein asserts that education is undeniably necessary. The enemy is a conservative pessimism, the belief in a golden yesteryear and a famished tomorrow. The education of yesterday may have been better for some, but certainly not for women, blacks, Jews and other minorities and, least of all, for those in the lowest economic strata. “Misplaced nostalgia,” he states, “makes for bad public policy.” Hope, on the other hand, is what separates humans from animals.

Armed with hope, Botstein calls for a cradle-to-grave reassessment of the meaning of education in a democracy, how we educate ourselves, not just as children but throughout our lives. He intersperses thoughts on Headstart, affirmative action, family values, political correctness and neoconservatism with cold statistics and fire-breathing metaphors from Wagner, Mozart and the Olympics. “Our national enthusiasm for regular physical fitness,” he writes, “must find its mirror image in mental fitness. . . .”

But “Jefferson’s Children” is not all theory. Botstein’s Twenty-Four Maxims for Adults, open-ended recommendations on how adults can educate their children beyond the frontiers of the school day, could give any family a month’s worth of dinner table conversation.

*

Undoubtedly, it will be Botstein’s recommendation for the abolition of the American high school that will draw the most fire. Botstein suggests redividing primary and secondary grades as K-6 and 7-10 and graduating children at age 15 or 16. At its simplest, the argument grows from the premise that, with advances in nutrition and health care, physical maturity arrives two years earlier than it did 100 years ago. Combined with the recent belief that children profit from serious schooling at the age of 4, the result, according to Botstein, should be a re-jigging of the traditional 13 school years into 11.

Botstein then describes a host of advantages that would accrue, from the educational and financial (those two years of public funding saved could be reinvested as vouchers for students wanting to go on to public universities or two-year colleges) to the extraordinary (the abandoned high school buildings in inner cities could be turned into 24-hour safe havens for youths to find secure places to interact with adults).

From there, it is a logical step to a rethinking of teacher training, undergraduate education and teaching. Botstein may not convert the philistines who refuse to give up their nostalgia for a vague past of three Rs and 2.2 children. But he gives the gift of hope to the agnostics, who are more confident of their dissatisfaction with the current system than of their beliefs in reform.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.