Dead Sports Legends Can Still Play Hardball

- Share via

SUN CITY, Ariz. — Babe Ruth’s daughter, Julia Ruth Stevens, used to get a royalty check every few years, about $100 apiece from companies that felt guilty about using her famous father’s image.

“Most people didn’t bother to ask me for permission to use Daddy’s name,” Ruth Stevens said, “and there wasn’t a lot I could do about it.”

Then she hired an agent. The 80-year-old now collects more than $100,000 a year.

Many dead celebrities have more earning potential as pitchmen now than when they were alive. With a campaign centered around a deceased star, advertisers don’t have to worry about a scandal erupting around their key spokesman, and technology allows them to manipulate old images around new products.

“The obvious advantages is that you have a very consistent image that’s fixed in time that won’t deviate from the message,” said Mark Roesler, founder of CMG Worldwide, which represents Ruth Stevens.

The Fishers, Ind., firm holds marketing rights to about 120 deceased stars, including Lou Gehrig, Jack Dempsey and Vince Lombardi, as well as some living former stars such as Jim Palmer and Johnny Unitas.

Even though most of CMG’s endorsers are dead, their support doesn’t come cheap. Roesler said advertisers typically spend $5,000 to $15,000 to use a deceased celebrity in their campaign. CMG, with $15 million in revenue in 1997, keeps about half of that.

“The common denominator with all of our clients is: They weren’t doing any business before they got involved with us,” Roesler said. “It wasn’t a tough sell when they saw what we did for some of the clients who were in similar circumstances.”

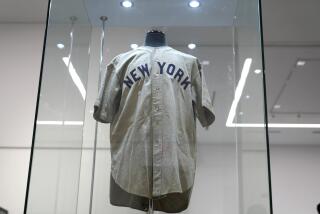

In 1995, CMG launched an aggressive campaign promoting Babe Ruth’s 100th birthday. It raised more than $1.5 million from companies paying for the right to put his image on beer steins, coins, watches, even computer mouse pads.

“I had no idea it would be as big as it was,” said Ruth Stevens, who has a winter home in Sun City. “This helped out tremendously, especially considering I was diagnosed as being legally blind when my mother died in the late ‘70s.”

While CMG said its revenue has increased 50% in two years, there could be even better years ahead as the company prepares a marketing blitz focusing on legends of the 20th century.

For years, dead celebrities were free pickings for companies looking for well-known salespeople. That began to change in the mid-1980s when CMG, which was first hired to protect artist Norman Rockwell’s Saturday Evening Post covers, recognized what it says was an industrywide trademark infringement.

“We realized this is a real niche,” said CMG President Darci Ross. “We were calling clients and they were calling us telling us they wanted to be protected.”

In 1993, Time-Warner Inc.’s Warner Bros. was ordered to pay CMG and the family of James Dean $1.6 million over the merchandising rights to Dean’s likeness and image. Since 1984, Dean’s image has generated more than $30 million.

CMG’s seven-member legal department sends out an average of 600 letters a month warning companies to stop using images and audio clips to which CMG retains the rights. Of those, about 10 to 15 cases go to arbitration a year and four cases on average reach a trial.

Ryan Schinman, a vice president with competitor Worldwide Entertainment & Sports, said CMG could triple or quadruple its revenue before the end of the ‘90s.

“We’d love to have a slice of that business,” said Schinman, whose West Orange, N.J., company represents more than 75 sports celebrities. “The people CMG has are icons, and what they can do with technology is mesmerizing. People die every day and families want to sustain images.”

With technology that can make Fred Astaire dance with a vacuum cleaner and John Wayne appear in beer commercials, CMG’s Roesler said having deceased celebrities as endorsers will gain in popularity.

“I often say we’re in the technology business,” he said. “We’re soon going to be able to do whatever we want with video, audio, photographs. We’re almost there now.”

For Ruth Stevens, the technology has made for a better retirement.

“This money has been a godsend,” said Ruth Stevens, who worked as a retail assistant manager for $75 a week in the late ‘60s. “It’s funny that in Daddy’s best year, he only made $80,000 and now I’m receiving more than that.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.