U.S. Will Strike Again if Iraq Resumes Weapons Program

- Share via

WASHINGTON — A day after their air assault ended, U.S. officials said Sunday that they are prepared to resume strikes on Iraq at any time--and that military planning for a new assault has already begun.

Yet Clinton administration officials privately acknowledged that plunging back into an air campaign would involve substantial diplomatic complexities. For one thing, with Iraqi defiance apparently having put United Nations weapons inspectors out of business, there would be no internationally sanctioned group on the ground to gather information on Baghdad’s weapons program or to help make a case for any new attack.

As the conflict with Iraqi President Saddam Hussein entered a new and ill-defined phase, however, officials asserted that any sign that Iraq has resumed its banned weapons program will bring a new series of strikes.

“We remain in place,” said Gen. Henry H. Shelton, chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff. “And so, if he tries to reconstitute that capability, we’re prepared to take it down again.”

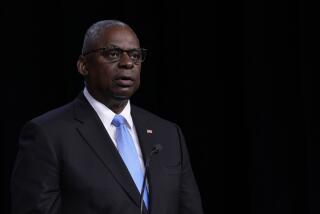

Defense Secretary William S. Cohen said Hussein probably will try to repair and rebuild the approximately 100 sites hit in four nights of bombings. The United States will try to make that as difficult as possible, Cohen said, by resuming its enforcement of “no-fly” and “no-drive” zones in Iraq, as well as by interdictions at sea and economic sanctions against the regime.

“The burden of proof really is on Saddam. He is going to continue to live with the restrictions. . . . We’re going to continue to be there,” Cohen said on CBS-TV’s “Face the Nation.”

Military officials said the process of picking a new set of targets also is well underway.

But if the United States wants to renew the attack, it presumably will have to gather its own information on Hussein’s activities, rather than relying on U.N. inspections, and then sell its arguments for new strikes to the world.

It was not easy to make the case for strikes even with the U.N. inspectors on board. “Without them, we’re looking at a bunch of new problems,” a U.S. official said recently.

Meanwhile, Baghdad sharply increased its claims of civilian casualties from the bombing.

Nizar Hamdoun, the Iraqi ambassador to the United Nations, said the bombing had inflicted “enormous damage, mainly to the civilian infrastructure and to human life. I am told the casualties are in thousands, in terms of people who were killed or wounded, but we don’t have any final figures,” the ambassador told CNN.

Hamdoun did not address the question of military casualties from the bombardment, which the Iraqis have not spoken of, possibly to avoid spreading alarm among troops who are essential to Hussein’s regime.

Previous estimates from Baghdad had the civilian toll at 42 dead and 96 wounded.

The Pentagon was still considering Sunday whether to start reducing the forces it began strengthening over the course of the past week. Some of the aircraft, troops and equipment had not yet even arrived in the Persian Gulf.

Military officials, who had been weighing whether to increase U.S. forces in the Gulf in the aftermath of the strikes, apparently are likely to keep them at about the level they have been.

The military usually has had between 17,000 and 20,000 soldiers, sailors, Marines and airmen in the region, including those aboard the Navy ships that rotate through the Gulf. The number has been as high as 40,000, which was reached last winter during threatened strikes on Iraq.

But officials said Operation Desert Fox showed that the forces in the region could carry out a large strike without much reinforcement from the United States. The approximately 650 aircraft sorties and more than 400 cruise missile strikes were all completed with forces already in the region, except for some B-52 bombers that were flown in and that carried a complement of air-launched cruise missiles.

“This was done substantially with forces that we have in the region day in and day out,” one defense official said. “I’m not sure people understood what we routinely have there.”

The issue involves a delicate balance. The Pentagon wants to have enough force on hand but to avoid straining the defense budget and disrupting troops’ lives unnecessarily amid a brisk pace of worldwide deployments.

In addition, U.S. officials need to keep the lowest profile possible for the weapons and forces assembled in many countries, to avoid arousing public animosity.

Saudi Arabia, for example, refused to allow the United States to use the 60 combat planes based on its soil in the air assault, even though Saudi officials have in the past given permission for the Pentagon to use noncombat support aircraft in such attacks on Iraq.

The 70-hour Operation Desert Fox, which has been described by officials as the largest military mission of the Clinton years, involved more cruise missiles than the 1991 Persian Gulf War. But by other measures, it was a limited operation: The second-largest Clinton-era operation, the three-week NATO bombardment of Bosnian Serb troops and equipment in 1995, involved 3,500 sorties.

Also, the 200-plus Navy, Marine and Air Force planes used in Operation Desert Fox pale compared with the 2,700 planes used in the Gulf War. And the total troop complement of 24,000 contrasted with 700,000 mobilized eight years ago.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.