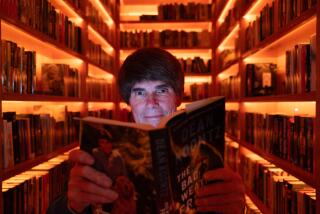

Captivated by That Koontz Momentum

- Share via

Blame snobbery, perhaps, or the fact you can’t get around to everything, but this is the first Dean Koontz novel I’ve read. Meanwhile, some 200 million copies of his previous 35 books have sold worldwide, according to his publisher. It’s a weird feeling to turn a street corner and happen upon a parade so big and brassy after so much of it has passed--and to find, on opening “Seize the Night,” that the world is already coming to an end.

This is a sequel to “Fear Nothing,” which Koontz set in a California coastal town, Moonlight Bay, next to Fort Wyvern, a 134,000-acre Army base where sinister, black-budget genetics experiments took place during the Cold War. The base has been closed, but the labs may still be operating underground. The government has imposed covert martial law, muzzled the media and assassinated any potential whistle-blower, while desperately trying to find an antidote for a retrovirus that has escaped into the civilian population and may alter every form of life on Earth beyond repair.

The hero, 28-year-old Christopher Snow, was born with a rare disease that makes him vulnerable to light. He must live in the shadows--and with the knowledge that his mother, the scientist who invented the retrovirus, cooperated with the military in a misguided attempt to cure him. Snow’s parents have been murdered. His own life has been spared, he believes, only because the authorities think he might somehow help them solve the puzzle. Moonlight Bay’s cops have been corrupted. Snow can trust only his genetically altered, super-intelligent dog, Orson, and a small group of surfer dudes and chicks who have been his lifelong friends.

On the very first page of “Seize the Night,” Snow, riding his bicycle through Moonlight Bay after dark, discovers that the 5-year-old son of one of his friends has been kidnapped. He and Orson follow the trail into Fort Wyvern. The next 200 pages are one continuous scene in which Koontz blends in the necessary background from “Fear Nothing” while never relaxing the suspense. Snow can barely deal with one peril or enigma--a descent into creepy sub-basements, an attack by a club-wielding psychopath, Orson’s disappearance, vicious super-monkeys, crazed nighthawks and coyotes, a big, apelike mutant, the body of an Army officer who committed suicide, a tape indicating that the genetics experiments may have been only a sideshow to the real horrors of Wyvern--before the next is upon him, and us. It’s a remarkable technical feat.

Surely this ability to articulate his scary visions in such detail and to keep the level of excitement so high, moment by moment, is a main reason for Koontz’s popularity. If we had time, we might see the mad-scientist stuff as derivative, the isolation of Moonlight Bay from the rest of the world as contrived, the effectiveness of the government cover-up as both a paranoid and an unlikely notion, given the gabbiness of our society. (If Monica Lewinsky’s taste in underwear is no secret, how could the end of the world be?) But Koontz never gives us a chance to look back. The impetus is always forward.

Another basis for his appeal is that Koontz, unlike most thriller writers, seems as interested in good as in evil. Snow is an engaging narrator; his effort to lead a normal life despite his handicap has prepared him to uphold humane values in a time of metaphysical darkness. His friends, morally unshakable and loaded with useful talents, are hardly ordinary people, but their caring for one another and their laid-back surfer humor seem ordinary in this context; they give us the illusion that we, too, could fight successfully against such odds.

After a pause while the sun shines, the search of Wyvern--for three missing kids now--resumes. In another continuous scene, Snow and his friends encounter a mass suicide, a virus-infected priest who is “becoming” something other than human, a serial killer whose victims are burnt offerings to Satan and a subterranean chamber that opens onto a parallel universe (red sky, black trees, winged demons) that might as well be Hell. It’s not quite as plausible as the first scene--we accept genetic engineering as fact, whereas time machines are still science fiction--but it’s even more exciting. In the end, we barely have time to notice how many issues remain unresolved before Koontz has a Navy battleship approach Moonlight Bay. Uneasily, Orson “trotted closer to the water . . . sniffed the air.” What does he smell? Of course: another sequel.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.