Warp-Speed Capitalism

- Share via

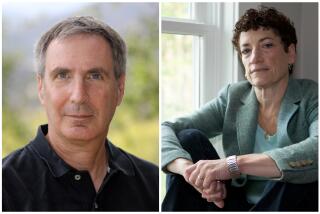

Dramatic titles often announce turgid books. Not in the case of “The Commanding Heights.” Daniel Yergin, Pulitzer Prize-winning author of works on many aspects of world affairs, and Joseph Stanislaw, distinguished scholar and international advisor, have produced a book that must be read by anyone who responds to its powerful subtitle.

The “battle” that Yergin and Stanislaw describe is already familiar to us. It began with the decline of the Soviet regime that started in the 1960s, followed by the fall of the East German government that eventually brought about the end of socialist governments in Poland and elsewhere. During these same years, China had its “Russian” crisis in the near coming apart of communism under Mao Tse-tung’s Cultural Revolution, which led to a gradual movement toward ever more market-oriented regimes, not only in China but throughout virtually all of Asia, North Korea being a tragic exception.

Meanwhile throughout Europe, from England to Czechoslovakia, we have seen the less spectacular but no less important movement of socialist-minded governments toward capitalist-oriented economies. Where bureaucrats once reigned, markets now make the decisions. When Tony Blair, the highly popular leader of England’s Labor Party, was overwhelmingly elected last year, one of his early acts was to invite Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street for a talk.

There is no doubt that, over the last 30 years, the pendulum of political economy has been swinging to the right, away from socialism toward capitalism. Yergin and Stanislaw tell this story in a manner that mixes the immediacy of personalities with the more impersonal issues at work behind the scenes. They do so, moreover, without making government a villain and the market a hero.

Indeed, what gives credence to their analysis in “The Commanding Heights” is their recognition that the role of government within capitalism is essential, just as the growing role of markets within any high-technology nation is inescapable. It would be all too easy to make a book such as this into a primer on conservative economic values, but to the authors’ credit, and very much to the readers’ benefit, the changes about which they write are treated as parts of a historic process, not a morality play.

What is ultimately behind this historical transformation? As Yergin and Stanislaw make clear, the first source of change is the growing complexity of capitalist economies themselves: a complexity that has brought in its wake the necessity for a much greater reach and penetration by government regulation. Here we need only think about our own history: It was the rise of the nationwide railroad system that brought into being the Interstate Commerce Commission, not the other way around; just as it was the growing instability of a big-business, big-finance economy that ultimately required a Federal Reserve System and a Securities and Exchange Commission, not vice versa.

But with the inevitable rise in the size and importance of government intervention has come the inevitable flip side of the coin: the growing capacity for the government to commit its own economic blunders. Inevitably this creates a reverse pendulum effect: The social villains of early capitalism are its robber barons; the villains of later capitalism, its bureaucrats. What gives distinction to the tale told by Yergin and Stanislaw is that this shift of political antagonisms is not portrayed as a battle against “capitalism” but as an understandable, and perhaps inescapable, aspect of capitalism’s own developmental thrust.

This leads to the conclusion that as business itself gains in power and scope, the pressures for a return of the pendulum may well increase. Indeed, our authors already see the first such source of a movement toward more government regulation in the growth of an international financial market capable not only of toppling individual governments but of imperiling the development of workable internationalized capitalism itself: The present Asian crisis is a case in point.

This brings us to a second possible cause of a reverse swing of the pendulum. It is the process known as globalization: the growth of worldwide companies that create pan-national structures of production and distribution. That process, utterly unknown in the textbooks of only a generation ago, now appears in every text either as a force of central importance in generating productivity and growth or as a source of dangerous vulnerability and decline. In fact, to different degrees, globalization quite possibly generates all these contrary effects in different places in the world. Think only of its effects in opening foreign markets to American products such as aircraft and its counter-effect of opening American markets to such products as computer parts produced in China or South Korea, not to mention Nike sneakers produced in Vietnam.

Once again, the growth of international capitalism is both an indicator of the immense vitality of the global market and, at the same time, possibly the forerunner of efforts to strengthen the defensive capabilities of governments whose political effectiveness prevents weak economies from retaining their organizational coherence and threatens them with being swallowed by larger markets. This sort of wide-ranging vision of the global economy is perhaps the single most effective characteristic that lifts this book, whose pro-market sympathies are outspoken, from becoming a mere voice of conservatism.

Indeed, “The Commanding Heights” ends on a note of caution, not celebration. The present emerges as a time of challenge, not fulfillment. For individual companies it promises--”warns of” might be better words--an intensification of competition, along with a corresponding need for a much more farsighted and sophisticated sociopolitical understanding than is generally manifested today. For individual nations, the book poses a prospect of new threats to traditional sovereignties as geographical borders melt away, while at the same time there arises an ever-growing need for international cooperation to produce global financial stability and to prevent worldwide ecological disaster. For the not-yet first-rank players (Russia, China, India, Latin America), not to mention the not-yet starters in Africa and parts of the Pacific, all this means finding a place in a world that has less room for countries without solid social, political and economic structures: countries that are more prisoners of, than players in, the world economy.

For Europe and the United States, Yergin and Stanislaw see somewhat different challenges. The first is to deliver acceptable standards of economic performance, especially with regard to levels of employment and rates of growth; the second is to develop acceptable levels of social performance, above all, that will address the gap between the quality and security of life on the bottom and at the top. The authors do not hesitate to say that the United States has succeeded far better than Europe with respect to the first of these challenges but not to the second. They quote Peter F. Drucker, perhaps the best-known and most influential conservative commentator on capitalism, as warning of a coming backlash of “bitterness and contempt” against the rich in the United States. Still other Euro-American challenges are discussed, including the astronomical size of the fiscal subventions needed to support the burgeoning numbers of senior citizens, a sum estimated by one economist as having the magnitude of a war budget.

But the mere enumeration of these challenges hardly suggests the richness of “The Commanding Heights,” whose breadth and depth of coverage are extraordinary; whose readability is irresistible; and whose educational importance cannot be overestimated. This may sound like an advertisement but it is, in fact, a review. It has been a long time since I have read a book in which intelligence and readability were so felicitously mixed.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.