Cow Egg Used as Incubator in Cloning Boon

- Share via

Using a cow’s eggs as incubators, scientists at the University of Wisconsin-Madison successfully cloned five different species, including primates, in an experiment that ethics experts expect will intensify an international furor over human cloning.

The new findings, which were to be presented today at a research meeting in Boston, offer evidence that the unfertilized eggs of one species can be combined with adult cells taken from a wide variety of animals.

So far, all the pregnancies have resulted in miscarriages, the researchers acknowledge. The Wisconsin scientists do not yet know whether they need to simply refine their techniques or whether, as a matter of fundamental biology, nature was rejecting their creations.

Nonetheless, several experts said it is the first independent confirmation of the technique used by researchers at the Roslin Institute outside Edinburgh, Scotland, to clone Dolly--the world’s first mammal made from an adult cell. Other researchers who cloned animals in an effort to duplicate that feat have used embryonic or fetal tissue, not fully developed adult cells.

But the Wisconsin experiment, which included sheep, pigs, rats, cattle and rhesus monkeys, takes the cloning of mammals into a new dimension by using the technology to combine different species, several experts in reproductive biology said.

Moreover, it suggests the molecular machinery responsible for programming genes within the cytoplasm of an egg may be similar in all mammals, the Wisconsin researchers said. That offers the possibility that eggs of one species can be used as a universal incubator for cloning any adult mammal cell, including--theoretically, at least--those of human beings.

If perfected, the new technique one day could have broad applications, from the development of customized tissue cell lines for human transplants, to more efficient ways of genetically engineering farm animals, the Wisconsin scientists said.

The findings raise a host of questions about whether this technique could, or should, be applied to human beings. The research is so new that no one has any clear idea what utility there might be in using human cells to create transpecies clones, by transplanting a human nucleus into an animal egg or vice versa.

“If it turns out you can do it so readily in other species, perhaps it can be done in humans this quickly as well,” said John Robertson, an expert in biomedical ethics at the University of Texas and co-chairman of the ethics committee of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine.

“It may be much too soon to even think of any human applications, but it indicates how quickly the science seems to be progressing here,” Robertson said.

At almost any other time, such esoteric insights into the subtle mechanisms of mammalian cells might attract little notice outside a select circle of embryologists, reproductive biology experts and venture capitalists.

But in the months since the public debut of the cloned sheep named Dolly, the broader scientific and medical community has become increasingly sensitive to the potential misuse of any new cloning techniques--so much so that earlier this month the mere suggestion that a Chicago scientist named Richard Seed was willing to undertake human cloning provoked a national controversy.

With public expectations and fears running so far in advance of experimental evidence, the newest research will almost inevitably heighten concerns over cloning experiments, several experts said.

“To me, this new research is simply further indication that the [cloning] technique has capabilities that are going to be relevant for human beings sooner rather than later,” said Alexander Morgan Capron, a biomedical ethics expert at USC and a member of a presidential bioethics commission.

“This is a dramatic reminder that the issue is not going to wait for society to catch up. It is not an issue that is going away,” Capron said.

Well aware of the public attention drawn to any cloning research, the Wisconsin researchers emphasized that their results are the preliminary findings of a highly experimental undertaking.

The researchers said in interviews that they have yet to produce any offspring with their technique, just a series of unsuccessful pregnancies in the host animals.

They are presenting their results in two research papers to be given at a meeting today of the International Embryo Transfer Society.

“The science is interesting, but any application is a long ways away,” said cloning pioneer Neal L. First, in whose Wisconsin laboratory the research was conducted by Tanja Dominko and Maisam M. Mitalipova. Even so, the university is seeking to patent their process.

When it started, the Wisconsin group was simply trying to duplicate the cloning experiment that resulted in Dolly, First said.

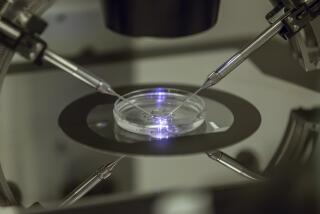

But the researchers chose to vary the experiment by using material from two different species, transplanting the nucleus of a cell from the ear of a grown sheep into an unfertilized cow’s egg. When that experiment showed some promising results, they immediately duplicated it with other species.

In each instance, the resulting creation appeared to be guided by the genetic programming of the new nucleus, so that a rodent nucleus produced a rodent embryo and a monkey nucleus produced a monkey embryo, even though each was growing in the cradle of a bovine egg.

“To our surprise, they developed all the way to pre-implantation embryos,” First said. “Our [embryo] transfers did establish pregnancies. With ultrasound, we would find something there, but [each time] it did not continue with a viable beating heart.”

Several experts, including embryologist Steen Willadsen--whose 1986 success in making multiple genetic copies of sheep by splitting cells from developing embryos foreshadowed recent cloning breakthroughs--questioned whether the Wisconsin technique would ever produce living offspring.

The nucleus from one species and the egg of another may appear at first to combine successfully, but there may be too much of a genetic mismatch for any resulting embryo to survive to term, Willadsen said.

“The biology of it will have to be sorted out,” Willadsen said. “There is no guarantee that it will be useful.”

Jacques Cohen, who pioneered human embryo freezing and a number of other procedures for manipulating human embryos, also questioned whether the Wisconsin technique would ever yield offspring. Cohen is working with Willadsen at the Institute for Reproductive Medicine & Science at the St. Barnabas Medical Center in New Jersey to transplant nuclear cells from human embryos into animal cells. Their research is aimed at developing a test for diagnosing human genetic diseases.

“There are many things that you can do when you are dealing with free-living embryos [outside the womb], so I am not surprised by this experiment,” Cohen said. “But I would be surprised if they can obtain offspring.”

In any case, there are so many unanswered questions about what it would mean for the health and safety of any creature created in this way that any human applications are only speculative, experts agreed.

Whatever its eventual application, the Wisconsin experiment serves an immediate scientific purpose, several experts agreed, which is to evaluate the basic biology of cloning.

“It is what we were hoping for,” said Alta Charo, an expert on law and medical ethics at Wisconsin and a member of the national bioethics commission. “This will help shed some light on how realistic and safe cloning might be.”