Charles McPherson: Still Scaling the Heights

- Share via

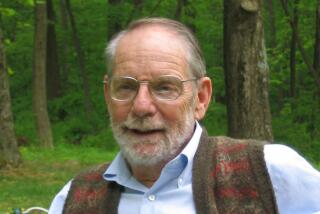

One word best describes the way Charles McPherson, the 58-year-old bebop-based alto saxophone master, played before a full house at Steamers Cafe on Saturday night: dazzling.

Not that this was anything new.

The Detroit-reared McPherson, who arrived on the New York jazz scene in 1960 and soon made a name for himself with bassist Charles Mingus’ Jazz Workshop and as a recording artist, has long been a superbly inventive Charlie Parker-influenced jazzman. As the years go by, McPherson simply keeps getting better, playing with more dynamism, subtlety, inventiveness and personality.

“Isn’t that what’s supposed to happen, that you improve as you age?” he asked rhetorically before his first set at the Fullerton jazz club.

The alto great, who heads this week to New York to play the Village Vanguard, commemorating the release of his fine new album, “Manhattan Nocturne,” offered several of the tunes he played at Steamers when last reviewed in The Times 18 months ago.

On the program were the originals “The Seventh Dimension” and “Manhattan Nocturne,” the timeless standards “Darn That Dream” and “Embraceable You,” and the classic jazz blues numbers “Billie’s Bounce” and “Blue N’ Boogie.”

McPherson, who performed with his quartet of Mikan Zlatkovich on piano, Isla Eckinger on bass and Chuck McPherson on drums, had complete concentration onstage. His eyes were closed as he played, his body moved only slightly and his fingers stayed close to the keys of his vintage King saxophone, a style of horn played by Parker and another alto giant, Cannonball Adderley. And despite a virtuosic technique, McPherson didn’t waste notes; there was a grand logic to what he delivered.

*

The numbers highlighted various aspects of McPherson’s artistry, though at the center of everything was a vibrant, juicy tone that made whatever came out of his instrument have an immediate impact and appeal. The opening “Boogie,” taken at a fast clip, found the alto saxophonist unleashing a seemingly endless font of ideas. Brief spinning phrases, lines that leaped from horn bottom to top, gorgeous twist-turn melodic garlands, bluesy bursts, the leader wove all these and more into a compelling musical tapestry. “Billie’s” and “Cherokee” were similarly enthralling.

The slower “Seventh” and “Nocturne” were examples of McPherson’s affinity for exotic non-bop moods, where the rhythms had a Latin or Middle Eastern feel and the themes occasionally lingered on held notes. In his solos, he revealed a deeper, more thoughtful side of his work, juxtaposing sweet, fat tones with more insistent, note-rich statements.

Zlatkovich, who is from Yugoslavia, provided good contrast, mixing bits of his primary influence--McCoy Tyner--with a helping of Bud Powell and a dash of Oscar Peterson into an agreeable style. He got a big sound out of the piano, offering firm accompaniment and soloing with a modern melange of crisply articulated lines, rolling tremolos and block chords. Eckinger added big tones to the support crew, and Chuck McPherson, the leader’s son, pushed the band with considerable energy and fire without being overly loud.

Although to some ears McPherson’s performance might have seemed perfect, the artist knew better. During a set break, a youthful saxophone hopeful said to the alto player, “Maybe if I keep practicing, I can play as well as you can.” McPherson replied: “Maybe if I keep practicing, I can play as well as I can.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.