Little Girl Lost

- Share via

When towering Abraham Lincoln met tiny Harriet Beecher Stowe, or so the story goes, he peered down at the woman whose “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” had inflamed the North against slavery and said, “So this is the little lady who started the big war.” And so it is on finally seeing “Lolita.”

Shown to and refused by studio executives early in 1997, debuting in Europe in September and finally opening in Los Angeles 10 months later for a one-week Academy Award-qualifying run before going nationwide Aug. 2 on Showtime, “Lolita” seems hardly likely to have caused so much trouble.

Was this reverential, overly long version of the Vladimir Nabokov novel going to start a conflagration in the hearts of the religious right? Was this careful, respectful but only sporadically involving vehicle the bombshell guaranteed to outrage moralists across America? Surely, there must be some mistake.

“Lolita’s” subject matter of a grown man engaging in a sexual relationship with a pre-pubescent girl has been understandably controversial since Nabokov’s brilliant novel was published in France in 1955 and went on to sell 14 million copies in this country. And the congressional passage in 1996 of the Child Pornography Prevention Act, precluding the use of body doubles by forbidding even what “appears to be a minor engaging in sexually explicit conduct,” cast more of a chilling effect and made reediting on “Lolita” a necessity.

But on seeing the finished film, the pious spin the filmmakers have put on the chronicle of their lack of success in the American market--a tale of besieged genius confronting soulless philistines, of dark threats to creative expression and 1st Amendment rights--seems lamentably self-serving.

This is not the case of a brilliant film sandbagged by the nattering nabobs of negativity, but rather a rarefied, arty, distinctly noncommercial work whose refined air and considerable cost (a reported $58 million, double its original budget) clearly were as much factors as the threat of controversy in keeping distributors away.

Paradoxically, “Lolita” is also the least likely movie to have been made by director Adrian Lyne, whose previous works include such non-art-house fare as “Flashdance,” “Fatal Attraction,” “9 1/2 Weeks” and “Indecent Proposal.”

A passionate admirer of the Nabokov novel, Lyne, having rejected screenplays by Harold Pinter, David Mamet and James Dearden, elected to follow Stephen Schiff’s careful script, retaining the novel’s late-1940s setting and turning great stretches of Nabokov’s hypnotic prose into voice-over material.

But though this “Lolita” is closer to the book than Stanley Kubrick’s dazzling 1962 version (which starred James Mason, Sue Lyon and Peter Sellers), respect has not served it particularly well. Except for a memorably haunted performance by Jeremy Irons as the conflicted Humbert Humbert, what the new version lacks most of all is inspiration.

Humbert is the film’s narrator as well as its protagonist, and it’s his sad voice we hear crooning, “Light of my life, fire of my loins, my sin, my soul, Lolita,” as, spattered with blood with a revolver next to him, he erratically drives his car along a country road.

Most of the film is a flashback from that moment, but before that can begin we go back even earlier, to Humbert’s childhood, when he fell deeply in love with a girl of 12, only to have her die of typhus. “The shock of her death froze something in me,” he remembers. “The child I loved was gone, but I kept looking for her--long after I had left my own childhood behind.”

Humbert’s tale proper begins in 1947 in the New England village of Ramsdale, where he has gone to spend a quiet summer before he begins teaching at nearby Beardsley College. Humbert inquires about a room rented by the affected Charlotte Haze (Melanie Griffith) and is about to turn it down when he catches sight of young daughter Lolita (Dominique Swain), lolling casually under a lawn sprinkler and smiling innocently through her dental retainer in a way he finds irresistible.

Humbert is, he tells us, a connoisseur of what he calls the nymphet, “the little deadly demon” with power enough to cloud his normally reasonable mind with thoughts of lust. From that moment on, Humbert’s entire waking life is devoted to trying to seduce Lolita, to make her his own. It’s a quest that takes strange turns, including the involvement of a mysterious author named Clare Quilty (Frank Langella), and has unlooked-for results.

It should be emphasized that though sex is very much on its mind, this “Lolita” is not prurient and not meant to be. What drama it has focuses on Irons’ expert rendition of Humbert’s various comic-tragic agonies, the contortions he has to go through to sustain a relationship with someone who, after all, is only 14.

Swain, who was a 15-year-old sophomore at Malibu High when filming began, does a respectable job as Lolita, but through no fault of her own this character is more problematic than Humbert’s. For one thing, in an age when a supermodel like Kate Moss can become an international sexual icon partly because she looks 15, Swain doesn’t, as Sue Lyon didn’t, really look as young as the novel has you imagine her.

Nabokov’s book is a problem in another way: It is largely narrative, with very little dialogue. Though “Lolita” tries to remedy this with extensive voice-over, the movie has no choice but to replace the novel’s incandescent language, its major source of excitement, with the kind of not particularly edifying dialogue that tends to come out of a 14-year-old’s mouth.

When Kubrick’s “Lolita” was released in 1962, the ad line teasingly asked, “How could they make a movie of Lolita?” A more appropriate question for this version is not how could they do it, but how could such a sincere, well-meaning effort end up so ineffectual on the screen?

* MPAA rating: R, for aberrant sexuality, a strong scene of violence, nudity and some language. Times guidelines: full frontal male nudity and gory violence in the film’s finale.

‘Lolita’

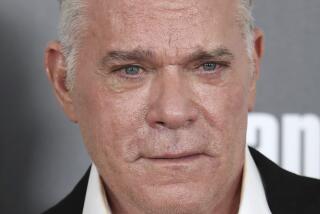

Jeremy Irons: Humbert Humbert

Melanie Griffith: Charlotte Haze

Frank Langella: Clare Quilty

Dominique Swain: Lolita

Released by the Samuel Goldwyn Co. Director Adrian Lyne. Producers Mario Kassar, Joel B. Michaels. Screenplay Stephen Schiff, based on the novel by Vladimir Nabokov. Cinematographer Howard Atherton. Editors Julie Monroe, David Brenner. Costumes Judianna Makovsky. Music Ennio Morricone. Production design Jon Hutman. Art directors Jon Hutman, W. Steven Graham. Running time: 2 hours, 17 minutes.

* Playing exclusively for one week at Landmark’s Cecchi Gori Fine Arts Theater, 8556 Wilshire Blvd., Beverly Hills, (310) 652-1330.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.