SWITCH HITTERS

- Share via

Pitchers Benny Flores and Erasmo Ramirez decided last summer to transfer to Cal State Fullerton because they wanted to improve their chances of reaching an NCAA regional tournament and possibly the College World Series.

Infielder Nakia Hill went the other direction, switching from Fullerton to Cal State Northridge because he saw more opportunity to play regularly and improve his prospects in the major league draft.

None of them probably would have made those moves if college baseball operated under the same NCAA rule as Division I basketball and Division I-A football: Transfer from one four-year school to another and sit out one season.

But as it stands, a college baseball player can move from one team to another almost at the drop of an aluminum bat. And more players seem to be looking for a quick fix for unhappy situations.

The NCAA keeps no records of the number of transfers each year in any of its sports, but San Diego State Coach Jim Dietz believes the number in baseball is increasing. Dietz estimates he has received more than 100 phone calls in the last year relating to athletes interested in transferring.

“This seems to be a bumper year,” Dietz said. “On one day alone recently, I had six calls. It seems almost like an epidemic.”

Marco Estrada transferred to Fullerton in September after playing two years at El Camino College. But he was playing for Northridge when the season opened Jan. 20.

Estrada saw the writing on the wall at Fullerton--too many shortstops ahead of him--and was gone by the end of December.

“I tell people he was the player to be named later in the earlier trade,” Northridge Coach Mike Batesole said jokingly.

Batesole is among the coaches who support what amounts to a limited form of college baseball free agency--the NCAA’s one-time transfer rule--because they feel it is in the best interest of the players.

“If a program doesn’t work for a player, either because of a lack of playing time or a coach’s personality, then the player should have a chance to go somewhere else,” Fullerton Coach George Horton said. “It makes it a lot easier if the athlete doesn’t have to sit out a year. The only time it gets complicated is if the coach and the player don’t agree.”

A school can refuse to release a player from his scholarship, forcing him to sit out the next season or go to a community college. But that rarely happens.

“Most coaches don’t want a kid who they know isn’t going to be loyal to their program,” Horton said. “Usually both the coach and the player are on the same page.”

UCLA Coach Gary Adams also supports the rule, but has mixed emotions.

“There are so many different reasons why players transfer, and I go back and forth on the rule,” Adams said. “I am concerned about the lack of loyalty the rule inspires, but my policy always has been that if a player doesn’t want to play for me or at UCLA, I’m not going to try to hold him. I always lean in favor of what is best for the player.”

Long Beach State Coach Dave Snow has a similar opinion.

“The baseball rule makes it a lot easier for either the player or the coach to walk away from a commitment they both made,” Snow said. “But it does give a player an opportunity to revive a career that might be in trouble. It’s a double-edged sword.”

USC Coach Mike Gillespie, however, opposes the rule and would like to see it change, but has been rebuffed within his own conference.

“The rule has had little effect on us, but I think it’s an unhealthy situation,” Gillespie said. “I think it benefits only the player, and makes it all too easy for a player to leave after a school has spent time and effort developing him. I proposed in our conference that we take a motion to the NCAA to change it, but I was voted down.”

Some conferences have penalties that limit transfers within their own schools.

The Big West requires a player to sit out one year and lose a season of eligibility. The Pac-10’s basic rule calls for a player to sit out two seasons, but allows for waivers to reduced limits based on various factors, including the amount of financial aid involved.

Gillespie is concerned that the NCAA rule can be exploited.

“I have no evidence of that, but the potential is obvious,” Gillespie said. “In the case of the Northridge pitchers going to Fullerton, I know that case was totally above board. We were made aware they were going to be available also, but we had already committed our scholarship money.”

Snow shares Gillespie’s concerns and is wary of situations where players from various schools play together on summer college league teams.

“I’ve heard talk about coaches using their own players to recruit other players in situations like that,” Snow said. “That’s wrong and if that happens too often the NCAA will have to take a hard look at the transfer rule.”

The freedom to move from one school to another also puts pressure on coaches to provide playing time early in a player’s college career or risk him leaving. Many top players plan to play only three seasons in college until they become eligible again to sign a pro contract.

“A player still has to show a reasonable amount of patience,” Adams said.

Horton agrees and said, “That’s the downside of the rule for me. It lends itself to a lack of perseverance on the part of the player. Sometimes you see guys who want to transfer at the drop of a hat. They’re not willing to battle for a position, and that’s not healthy either.”

Hill chose to leave Fullerton for Northridge, as did pitcher Tim Baron, and later Estrada.

Hill started in 55 of 64 games as a sophomore at Fullerton and batted .357 with seven home runs, but was told that his playing time would probably be limited this season. Hill said he would have asked for his release anyway because of a personality clash with an assistant coach.

“I didn’t know what to expect moving out of a program of the caliber of Fullerton’s, and I was a little concerned at first, but it has turned out great for me,” Hill said.

Hill leads Northridge with a .417 batting average and has 13 homers, 38 runs batted in and 12 stolen bases. Batesole says Hill has become a team leader.

“He’s been a great kid to coach and he’s had a great year for us,” Batesole said. “He played the first 15 games at shortstop and he had some problems defensively there, but since we moved him to second base he’s been outstanding.”

Hill believes his stock with pro scouts has gone up this season.

“I know I’ve gotten better,” he said. “I’m more relaxed. If I had stayed at Fullerton, I’m not sure I would be playing much.”

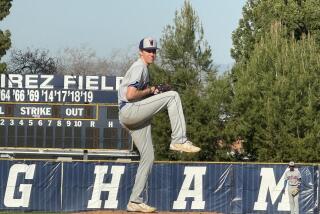

Flores and Ramirez are pleased they transferred to Fullerton.

Flores is 11-0 with a 3.13 earned-run average and Ramirez is 8-5 with a 3.77 ERA for a team that leads the Big West’s Southern Division. Barring a collapse, the Titans (40-12) should receive an at-large bid in the NCAA playoffs, regardless of whether they win the conference tournament.

Flores and Ramirez were denied that opportunity a year ago when Northridge, despite its 42-20-1 record, was snubbed by the NCAA selection committee.

“It’s worked out well for us,” Ramirez said. “We wanted to go someplace where we’d have a good chance to win and go to a regional. I still have a little bit of myself at Northridge, but I know we made the right decision.”

Another Northridge player, outfielder Terrmel Sledge, transferred to Long Beach State when it appeared the program was going to be dropped. Sledge is batting .352 with seven home runs and 19 stolen bases.

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.