Pianist Ray Excels in Rarely Heard Piece

- Share via

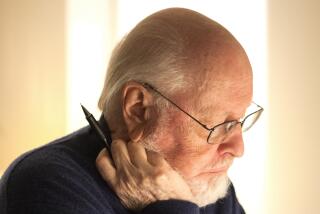

Morton Feldman’s place in American music has been growing steadily and spectacularly in the decade since his death. Next year around this time, when the inevitable lists of the most important American composers of the century are drawn, he may well be near the top of some. Europeans, especially, hold him in such regard.

Yet, important as Feldman’s music is, utterly beautiful as it is, profound in emotion and form as it is, we don’t hear it often in concert. And that too is the way it should be, as Vicki Ray’s radiant performance of one of Feldman’s late piano masterpieces, “For Bunita Marcus,” demonstrated Tuesday night.

Feldman, particularly in the late pieces, which are so very quiet, long and minimal, was a rarefied composer. A work like “For Bunita Marcus,” which lasts around an hour and a quarter (and is only a fraction of the length of some of the composer’s more extreme pieces), is not suited for a standard recital program. This is music that bends time. Single piano notes hang in the air. The first chord, which doesn’t come for several minutes, is an event. A proper mood of serene meditation must be established for a music meant to take us outside our daily lives and help us contemplate great thoughts.

Ray had the right environment with the Craftsman-style Neighborhood Church in Pasadena, where PianoSpheres was opening the fifth season of its interesting series. Feldman requires patience, but he gets to people, and a large audience gathered, including several schoolchildren.

The program felt, in many ways, like an offering. Ray’s concentrated and expressive playing nicely revealed the contradictory quality of music that seems entirely still yet is always in motion, music that redefines our sensations of stasis and movement. Feldman’s technique is to twirl short modules of notes this way and that, as if they were mobiles responding to a soft breeze. (Feldman once described it, in his memorably thick New York accent, as composing “module-y.”) No matter how well you may know the piece, you never really know what will come next, yet it all sounds so familiar and so single-minded.

Ray also added a novelty to the performance that didn’t work for me, although it may have for others, given the impressive attentiveness of the audience. She invited video artist Clay Chaplin to visually interpret the performance, especially with regard to John Cage’s “Lecture on Something,” which concerned Feldman’s music in the ‘50s, when it was extremely short and indeterminate (but still quiet). The video, which was created live, on the spot, sometimes showed the pianist’s hands in a kind of zombie-like time delay (which was not ineffective), but at other times it reproduced Cage text about Feldman or more abstract images (which proved distracting).

*

Feldman was a visual person. During the ‘50s, his friendships were more with painters in the New York School than composers. His music is made with visual forms in mind, be they collage techniques he got from Jasper Johns or Turkish rug patterns. And the greatness of the music is the way it translates spatial concerns to the purely aural. “Life goes on very much like a piece by Morty Feldman,” Cage says at one point in the lecture, “sometimes exciting, sometimes boring, sometimes gently pleasing.” Ray’s performance was true to life and its mysteries. Chaplin’s video, though not insensitive, was more informative and closer to science.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.