Metal Behemoths Punctuate Prairie Vistas in North Dakota

- Share via

REGENT, N.D. — North Dakotans don’t say “monotonous.”

They prefer “vast.”

As in: The state is vast. The land is vast. The sky is vast.

Locals luxuriate in all this vastness. But they understand that the average tourist craves a little something now and then to break it up--or, at least, to signal that here’s a town worth stopping in. Which is why North Dakota has developed an improbable obsession with gargantuan animal statues.

There’s glossy black-and-white New Salem Sue, the world’s largest Holstein cow. There’s the enormous, lumpy Jamestown Buffalo, reputed to draw 100,000 gawkers a year. Here’s the world’s biggest catfish. There’s a 26-foot-long walleye. Here’s a turtle crafted entirely out of 2,000 old tires.

But the grandest attention-drawing scheme of all pierces the horizon a few miles north of this proud little town of 265.

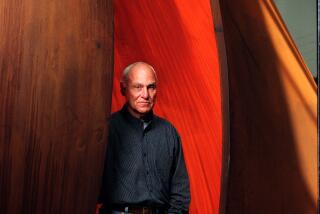

It’s the vision of Gary Greff, an unrepentant dreamer who quit his job as a junior high principal to come here, to his bleached-out hometown, to live on donated bread in a ragtag trailer while he builds outsize metal statues.

When he first moved back to Regent nine years ago, Greff dubbed the 32-mile stretch of road leading to town the “Enchanted Highway.” Since then, he’s dedicated his life to making sure the road lives up to that name by concocting fantastical sculptures all along it.

Greff’s first project was a towering “tin family”--the world’s largest, he boasts, and who could dispute it--made from old oil drums, ma’s hair a frizz of barbed wire, pa’s eyes unblinking hubcaps. Next he built a 9,000-pound silhouette, in iron pipe, of Teddy Roosevelt atop a rearing horse. Then came a shimmering pheasant family and a monster grasshopper clan hunkered down in a field of metal wheat. His current project: a flock of geese etched against a sun that will stand nine stories tall.

“I wanted to figure out, how could I get people down to Regent?” Greff said. “I imagined this whole highway with unique sculpture. But I realized, first of all, they couldn’t be normal sculptures. No one’s going to stop for normal.”

They do, apparently, stop for huge.

Local merchants--and there aren’t many in Regent--report with delight that tourists are finally starting to cruise the Enchanted Highway. “An extra 10 or 15 people a day,” claims Brenda Wiseman, who manages the small grocery. “It’s really noticeable.”

Sometimes they just take photos. But sometimes they’ll stop and fill up on gas. Or buy a soda or a slice of strawberry-rhubarb pie. Or pick up one of the Enchanted Highway T-shirts the town sells as a perpetual fund-raiser. A few have even popped by the bank to contribute to the cause. (The sculptures cost $12,000 to $15,000 apiece, and Greff is always in dire need of donations.)

Thrilled with the increased business, Regent residents are also proud that the sculptures lend an air of culture to their beloved farm town, which squats amid endless fields that roll in gentle hills to the horizon. Greff at first wasn’t sure whether his sculptures qualified as art, so he took some photos to a professor at North Dakota State University. “I didn’t want it to be just junk,” Greff recalled. “He said it was folk art. I said, ‘Oh, is that what you call it?’ ”

Now, nearly everyone in Regent agrees: It’s art, all right. Greff has even received regular grants from the North Dakota Arts Council.

“He’s not just putting a bunch of scrap metal together and calling it art,” said the council’s Darla Hueske. “It really is refined. As much as you can refine that kind of metal.”

Some of North Dakota’s 400 other outdoor sculptures might teeter a bit more uneasily on the line between art and junk. One photography professor has even been known to call them “the big uglies.” But residents--and tourists--seem to love them all the same.

“It’s the funkiness,” said Joanne Burke, the state’s deputy director of tourism. “We don’t know the numbers. But they do make people stop.”

Eager to add such a draw to their town of 700, residents of Steele, N.D., considered constructing a giant tumbleweed at their interstate exit. Or maybe a huge hay pile. But ultimately they stuck with the animal motif, selecting a sandhill crane, because their region is known for its birding.

The crane--the world’s biggest, of course--went up this summer. “And we’ve got people coming like you can’t believe,” said Susie White, owner of the Lone Steer Motel and Casino. “Well, not like you can’t believe,” she amended, “but at least 20 a day. I see them driving around it, and they’re laughing like crazy.”

Laughing?

“He’s ugly,” White explained. Then she added hastily: “But he’s gorgeous, too.”

Aside from its tourism potential, North Dakota’s menagerie on steroids might meet a home-grown need as well, serving as an artistic outlet for folks who have to drive an hour to a movie theater and much farther to a museum. “We have a lot of farmers and in the winter, they start to tinker,” Hueske said. “There’s a lot of creative energy out there.”

Or, suggested Robert Tubbs, who so loves the genre that he has documented every one of North Dakota’s outdoor sculptures: “There might be some feeling among folks out here that they want to leave something behind that’s bigger than they are.”

If so, mission accomplished.

Big time.

More to Read

Sign up for The Wild

We’ll help you find the best places to hike, bike and run, as well as the perfect silent spots for meditation and yoga.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.