Folk Art Picture Is Nod to Simpler Times

- Share via

Following a decade when “outsider” folk paintings were in, traditional themes are making a comeback, writes Marie Proeller in a recent issue of Country Living.

When the paintings of Anna Mary Robertson Moses, known as “Grandma” Moses (1860-1961), achieved widespread recognition 50 years ago, they struck a chord in the postwar American psyche. Her idyllic rural scenes represented a time of peace and plenty and possessed a childlike innocence that the public was eager to recapture. A similar phenomenon seems to be taking place today, as joyful scenes by contemporary folk artists are again garnering considerable attention.

“Collectors tend to return to traditional forms of folk art during times of great change,” confirms Jane Kallir, a co-director of Galerie St. Etienne in New York City. The gallery mounted Grandma Moses’ first one-woman show in 1940 and continues to carry her work today.

“Modern-day concerns have created an atmosphere that is not unlike what we saw in the United States at mid-century, when memories of war were still fresh and our agricultural base was vanishing,” she said. “At times such as these, people look for a connection to the past.”

In early America, self-taught artists traveled the countryside documenting homesteads, livestock and family members for a fee. The advent of photography in the mid-19th century offered a more precise way to record everyday life. This freed the folk artist to explore personal subjects in addition to representational ones.

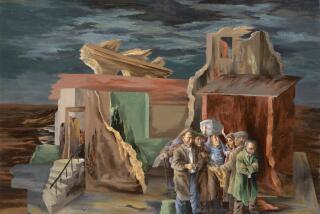

During the early decades of the 20th century, the work of self-taught artists was widely exhibited in museums and galleries. Paintings by John Kane (1860-1934) and Horace Pippin (1888-1946) and their contemporaries dealt with such issues as prejudice, love and loss, and industrialization’s effect on the rural landscape.

But it was the nostalgic themes of 80-year-old Grandma Moses, her childhood memories of farm life, that seized the public’s imagination. Demand for her work was so great that manufacturers produced posters, greeting cards, dinner plates and upholstery fabric with her bucolic imagery.

In the decades that followed Grandma Moses’ heyday, many self-taught painters continued to celebrate life’s simple pleasures, and they sustained a loyal collector base. But only recently has the work begun to regain the widespread popularity it enjoyed at mid-century.

Many experts view the recent strength of traditional themes in the folk-art market as a reaction to “outsider” art, a name given to the highly personal expressions of socially isolated people. While such art attracted significant media and collector attention in the 1980s and early 1990s, it has not achieved the broad appeal of pieces that expound on shared views and common experiences.

“People often tell me that they can’t understand the outsider material,” New York art dealer Frank Miele says. “More traditional themes need no explanation. This work is a celebration of all good things.”

Artist Kathy Jakobsen puts a positive spin on life. “I don’t promote negative things in my paintings,” she says. “If the subject of one of my pieces is New York City, I won’t put garbage on the streets; there are enough people doing that already! I paint the ideal, the way things should be and could be.”

While the increasing popularity of contemporary folk paintings has driven prices up in the past few years, it is still considered a relatively affordable genre within the art world, reports Marco Pelletier, owner of Gallerie Je Reviens in Westport, Conn. According to Pelletier, while works by today’s better-known folk painters can reach into the thousands, many fall within the $500 to $1,000 range.

Local crafts fairs, reports Country Living, can prove good hunting grounds for up-and-coming artists whose work often sells for $300 or less.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.