Retiring in the Fast Lane Just the Right Speed for Ex-Flier, 73

- Share via

ONA, W.Va. — Retirement for 73-year-old Harvey Simon is the stuff kids dream of and his peers fear: bumper-to-bumper traffic at more than 100 mph.

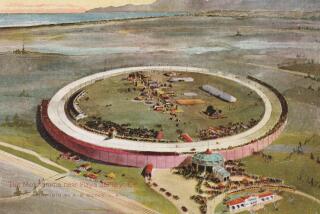

“Some people my age think there’s something wrong with me,” says Simon, who spends most summer Saturday nights racing his $30,000-plus late-model stock car around the paved, 5/8-mile track at Ona Speedway near Huntington.

The pudgy, silver-haired man from Cambridge, Ohio, knows he’s an attraction and doesn’t hesitate to play up his age. A caricature of him sitting in a wheelchair burning rubber graces a side panel on his red race car.

Groups of fans in Ona’s main grandstand along the front straight cheer for him as he speeds by.

“Everybody knows Harvey and everybody likes him,” says Steve Swann, a 21-year-old driver. “There are a lot of people who’ll root for him.”

But Simon is no gimmick.

“I wouldn’t be here if I ever thought I couldn’t win,” he says. “I don’t just want to ride around out there. That’s dumb. I’m looking forward to winning a race before the year’s out.”

His competitors take him seriously. Simon moved up to the late-model division after winning last year’s season points championship in what is known as the Charger class of the Legends series.

Legend cars, compact racing machines encased in 1930s-style Ford or Chevrolet bodies, are popular among beginning oval track racers. The cars cost about $13,000 and are powered by motorcycle engines that pull them down the straights at nearly 100 mph.

That’s how Simon got started two summers ago, shortly after retiring from his job as a helicopter pilot for Marietta Coal Co. in Ohio.

“At first he couldn’t do it very well,” says Ronnie Herald, West Virginia’s only Legend car dealer and one of Simon’s closest friends. “Once we got him on the right track, the old man was really a threat at any race.”

Herald, who races late-model cars as well, has been able to keep Simon in his rearview mirror so far this season but won’t count him out.

“He can handle the car . . . and I think he could be competitive given a little more time,” Herald says.

“I don’t think a lot of people realize what he’s done; it looks a lot easier than it is,” Herald says. “It’s really difficult to hold on to a car with that power-to-weight ratio and be competitive.”

Late-model cars, which weigh about 2,800 pounds, produce 550 horsepower. Drivers say they can get around a short track faster than a NASCAR Winston Cup car, which weighs 3,200 pounds and produces about 650 horsepower.

“This is a learning year--a step up in all respects, especially with the physical size of the car,” Simon says. “You can’t see out of it. You don’t know where your nose is until you hit the guy in front of you.”

Simon was perhaps better suited to adapt to stock car racing than most his age. Not only is he in good health, but in his younger days he raced an Austin-Healey in a sports car club near Los Angeles, where he grew up and worked his first commercial pilot job with Sinclair Oil.

As he grew older, Simon began yearning for the rush of oval track racing--the roaring engines, the emphasis on raw power and the aggressive maneuvering that makes trading paint inevitable.

It was almost as if he were getting younger. And since he’s been racing at Ona, he feels younger. At his last six-month checkup his doctor told him he was in good shape and that his blood pressure has dropped to more healthy levels.

Simon spends most of his time in his RV, which he drives between home and the track.

Racing is a money pit, swallowing about $15,000 a year in parts and tires, which Simon’s retirement and investment income easily cover, he says. Simon and Herald perform most of the labor themselves, which is fine by Simon, who does little else.

“Racing means about everything to me. I don’t know what I’d do without it. I have no clue,” Simon says.

As he sips red wine and nibbles on cheese in his RV, he reflects on his father’s death, caused by failing health within a year after he sold his Los Angeles-based wholesale paper business.

Although some would say Simon is living dangerously for a man his age, he credits racing with sustaining him.

“The worst thing a person can do once they retire is do nothing,” Simon says. “I’m convinced my dad died because he didn’t know what to do with himself.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.