Polio Pioneer Battles New Syndrome

- Share via

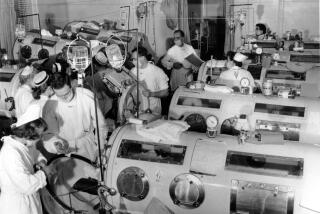

Back in the 1950s, pioneering orthopedic surgeon Dr. Jacquelin Perry performed spinal surgeries that helped paralyzed polio patients regain mobility after emerging from the iron prisons of mechanical ventilators.

Today at 81, Perry is seeing them again. Grown men and women who thought they’d beaten the stealthy infection that struck terror in them and their helpless parents decades ago and pushed the United States into a frantic but fruitful search for a vaccine.

“Patients are coming back to me [whom] I treated in ’55 and ‘56,” Perry says in the clinic at Rancho Los Amigos National Rehabilitation Center in Downey, which serves people whose polio is tormenting them anew.

“You don’t look back. You look at what you can do to help them.”

Perry’s goal is to staunch the deterioration, pain and muscle weakness wrought by post-polio syndrome, a little-understood aftereffect of polio. Slowly and insidiously, it reverses the gains that surgery and rehabilitation achieved for thousands infected by the polio virus. In about half of polio survivors, the symptoms turn up when muscles that compensated for polio damage give out unexpectedly.

Among the patients Perry has followed is Richard Lloyd Daggett, 59, of Downey. When Daggett was 15, Perry fused his spinal vertebrae. He walked unaided for 30 years. But post-polio landed him in a wheelchair she helped him obtain. Daggett, president of the Polio Survivors Assn., calls Perry “the most knowledgeable polio physician anybody knows.”

*

Officially, Perry is retired and off the Rancho Los Amigos payroll. But you’d never know by the hours she keeps.

Despite quiet struggles with advanced Parkinson’s disease, the grandedame of polio physicians continues to draw patients from around the globe 40 years after the Los Angeles Times named her 1959 Woman of the Year for medicine.

Parkinson’s has slightly thickened her rapid-fire speech, slowed her rise from chairs, and forced her to take a rest at midday. As she says: “You can do anything you want, but you can’t do everything.”

Perry continues to hike and camp and seems apologetic that her formerly 20-mile hikes are just two miles now.

Asked how patients react when they see that she, too, has physical limitations, she responds with impeccable comic timing: “They just worry I’m going to retire.”

Perry analyzes the biomechanics of walking in Rancho’s Pathokinesiology Laboratory, which she founded in 1968 after a brain artery blockage forced her to stop operating. She’s a consultant to the physicians, physical therapists and brace-builders at Rancho’s post-polio clinic. She teaches at USC and UC San Francisco, consults with Centinela Hospital Medical Center in Inglewood on sports medicine and conducts research.

Perry lives near the tree-shaded Rancho hospital complex, where three years ago the Jacquelin Perry Neuro-Trauma Institute was named in her honor. But home is really Rancho, where she pursues her first love, caring for patients.

“As far as I’m concerned, I’ve never worked. I do what I like to do,” she says.

Flashing an impish smile and observing keenly, Perry leans over a withered calf or thigh and quietly poses key questions as she determines the best way to bolster weakened muscles.

She presses her long, slim fingers into Erika Bonner’s abdomen and demonstrates how extra support “allows your diaphragm to rise to a higher level” and makes breathing less tiring.

“She picks up things real quick. I feel I’m in good hands,” says Bonner, a 39-year-old graphic artist from Van Nuys who contracted polio as an infant in the Philippines.

*

Besides relying on matchless instincts for how muscles and joints move, Perry understands human behavior. The very drive that helped polio patients overcome childhood disability gets in the way with post-polio. Perry must convince them to downshift to protect overtaxed limbs. She must help them adjust psychologically to braces, canes and wheelchairs after decades of freedom from such devices.

Perry instructs sufferers to simplify daily routines (a Herculean task for classic polio “pushers” who always go the extra mile), take rest periods and lose weight.

Tenure has brought “the advantage of authority” so that patients “expect to listen to me.”

Javier Robles, 49, of Highland Park worried more about how he would support his family than what he needed to do about his increasing pain and disability until Perry told him to “settle down.”

“She said that if you want to live long, do what I say. I said OK.”

Teri Loui, a 42-year-old nurse who recently flew in from Honolulu for a follow-up, says Perry was direct with her, too. Perry “had a little twinkle in her eye and a cute little smile. That’s why it’s so hard to imagine her scolding people.”

Loui complied by trading an exhausting clinic job for office work. Her husband, David, credits Perry with giving them both “hope we can do things to prolong Teri’s stamina and actually grow old together.”

*

As Perry hands over the reins to younger colleagues, she tries not to overshadow them. Speaking quietly of the co-director of the post-polio clinic, Dr. Sophia Chun, 33, she says: “I don’t trail her unless she wants help. Otherwise, she’s obligated to use me.”

Chun has formidable lace-up shoes to fill: “What’s amazing about [Perry] is, she can watch somebody walk and observe what muscles they’re using and which ones they’re not,” she says. “That’s what we’re all trying to learn from her.”

Perry was raised in downtown Los Angeles. The only child of a clothing-shop clerk and a traveling salesman, she was a latchkey kid long before the term was coined. She filled after-school hours with field hockey, basketball, lacrosse and reading.

“I knew at about age 10 that I wanted to be a doctor,” she says. “I read every medical book they had at the Los Angeles library.”

After graduating from UCLA, Perry became an Army physical therapist, treating polio patients in Hot Springs, Ark., during World War II. Out of a desire to “make my own decisions,” she studied medicine at UC San Francisco and became one of the first U.S. women to be board-certified in orthopedic surgery.

In 1955, Perry joined Rancho Los Amigos, where she collaborated with Dr. Vernon Nickel on polio cases. For spinal surgery patients, she designed, and the two developed, the halo, a metal ring still in use today that is screwed into the skull and immobilizes the spine and neck.

“We weren’t smart enough to patent it,” she says.

But then, as now, she wasn’t in it for money, but for the love of it all.

Jane E. Allen can be reached at jane.allen@latimes.com.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.