Like It or Not, ‘Like’ Is Probably Here to Stay

- Share via

If Al Gore had followed his mistaken belief that a politician should be a man of the people, he would have addressed Los Angeles in its own language. “Together,” he might have said, “we’re going to, like, take this ticket, like, all the way across America to, like, the White House this November.”

Linguistically, it’s not a difficult dialect, its main characteristic being constant use of the word “like.” When “like” replaces “say,” it’s a quotative, according to linguists. When it’s plopped here and there in a sentence, it’s a marker, signaling emphasis or hesitance or maybe nothing at all.

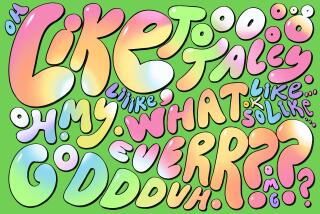

This faddish patois, usually traced to “Valley Girl” talk, was much discussed a decade ago in both academic journals and the popular press, though some said it was already on the wane. It was 1982, after all, when Frank Zappa’s hit song, “Valley Girl,” featured his then-14-year-old daughter, Moon Unit Zappa, riffing memorably: “Like, oh my God! / Like, totally! / Encino is, like, so bitchin’ / There’s, like, the Galleria /And, like, all these, like, really great shoe stores . . . .”

But like the Galleria, which is in the throes of a renovation, “like” is in no danger of going away for good. It thrives--not just around Los Angeles but in valleys and cities nationwide.

Actually, “nonstandard” usage of “like” goes back to the Beat Generation and hipsters of the 1950s, and in some forms even to the late 18th century. Even in standard grammar, “like” was always fairly elastic, serving as an adjective, an adverb, a preposition, even a conjunction. But there were rules, and purists irritably noted when they were flouted. They still bring up the 1954 slogan “Winston tastes good ‘like’ a cigarette should,” pointing out that grammar requires the use of “as” before a subject-and-predicate clause, whatever the colloquial usage. We’ve gone way beyond that. “Like” now permeates serious declarations as when a schoolmate of Kentucky teen killer Michael Carneal said in a deposition, “He told me that he would, like, get keys to people’s houses, and, like, just go up and unlock the door and, like, steal medication and stuff. . . . You, like, look back and you see all these little things that he did that were, like, sort of like warning signs. . . .”

To the common ear, the word seems just flung in. But academics abhor a vacuum, and linguists have strained to codify the function of the “nonstandard ‘like.’ ”

The “quotative” is the easier use to pin down: “Like” simply replaces the verb “say” when preceding a quote. To wit: “She’s like, ‘I’m not coming,’ and I’m like, ‘Oh.’ ”

The difference, wrote three Cornell linguists in a 1990 article in the journal American Speech, is that “say” introduces an actual utterance, however inexact. But “like,” they wrote, can also introduce “inner monologue . . . allowing the speaker to express an attitude, reaction or thought, as well as something actually said.”

“Like” also appears now as a “hesitant,” a replacement for “um,” “uh” and “er.” “You say ‘like,’ ” says UCLA professor of linguistics Pamela Munro, “to mark a pause while searching for a word to say next. If you look at transcripts, people use it before something they’re not sure of.”

Sometimes it’s a flag, functioning as “a marker of new information and focus,” wrote Cal State San Diego professor Robert Underhill, also in American Speech. His example quotes a bookstore clerk, asked for a particular book: “You go like in the back room and there like in the left corner.”

Another possibility is that “like” loosens a sentence, makes it less informative. A book that’s “like in the left corner” isn’t as firmly placed as one “in the left corner.”

“It could be conveying a state of mind,” muses Honolulu cultural anthropologist Arnold Green. “It says, ‘I’m coming on gently, non-assertive, not declaring God’s truth,’ in contrast to how adults talk to kids. It puts a little distance on the ideas.”

Even calling it a verbal hesitant may be an understatement. It’s really anti-verbal. The hipsters of the 1950s used the word “like,” says linguist Geoffrey Nunberg of Stanford and the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center, because they thought “ordinary language insufficient to express the nuances of the soul. [The word ‘like’] was a token of a distrust of language. It becomes among adolescents a deliberate inarticulateness.”

Today’s adolescents, moreover, are a generation “that doesn’t value articulation,” says Loyola-Marymount University visiting English professor Dorothy Clark. “They wouldn’t understand a William Buckley. Even ‘Wind in the Willows’ is too hard. They’re not involved in a language-rich environment, and they’re so unsure of the words to use that ‘like’ eases them over the decision.”

Actually, she laughs, “it’s easy to get sucked into it yourself. It’s comforting to feel you don’t need to say what you mean, but can just rest on the assumption that your ideas are transmitted telepathically.”

Perhaps its most important function--as with the Beats--is as “a marker of identity,” says Arnold Green. Indeed, says Munro, “the reason people use slang is to identify themselves as a part of the group that talks that way.”

“By the time kids are in junior high,” says Nathan Rubenson, 16, of West Los Angeles, “they just hear it all around and pick it up. They don’t know why they’re saying it: It’s just a reflex.”

“It’s like a tic,” says Clark, “a verbal addiction. Once you start using, you can’t stop.”

No wonder it’s, like, still spreading.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.