Bush the Son Uses Policy Campaign to Distance Himself From the Father

- Share via

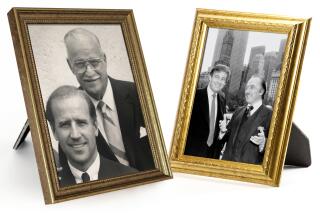

From some angles, George W. Bush can look eerily like his father, former President Bush. At times, when the Texas governor is mangling a sentence, he can sound like his dad too. But one of the most striking things about the son’s presidential campaign is how different it is from the old man’s. It’s a difference that points toward a very different presidency if G.W. Bush becomes only the second son to follow his father in attaining the White House.

When the elder Bush ran in 1988, his policy ambitions were modest in the extreme. He offered himself as a steward, not an innovator. Even the high points in his platform were relatively low hills: expanding Head Start, cutting the capital gains tax, providing more tax incentives for domestic oil exploration and protecting endangered wetlands. His most memorable campaign declaration--his acceptance-speech pledge of “no new taxes”--was a promise not to do something. With more candor than tact, one of Bush’s top congressional supporters memorably summarized this agenda just before the election by telling a reporter: “Sometimes, the dull periods are fairly good for the country.”

The younger Bush has pursued precisely the opposite approach. More reminiscent of Bill Clinton in 1992, this Bush has disgorged a torrent of policy proposals on virtually every aspect of domestic and foreign affairs. Some of these ideas have been modest, but plans such as Bush’s call for a sweeping across-the-board cut in income tax rates, a massive national missile defense effort and fundamental restructuring of Social Security and Medicare represent the sort of bold departures from which his father recoiled.

“There’s no question that Bush Jr. is somewhere closer to Ronald Reagan in terms of painting in bold colors vs. pale pastels,” says James P. Pinkerton, a top domestic policy advisor in the elder Bush’s campaign and White House. “The father’s natural instincts, especially on domestic policy, were all pale.”

Different political incentives explain part of the difference between father and son. One reason the elder Bush offered so few dramatic changes 12 years ago was that he was mostly making a case for continuity--for maintaining the direction of the outgoing Reagan administration. To the extent he presented a different direction, it was mostly a subtle promise to sand down the hard edges of Reaganism--an instinct embodied in Bush’s call for a “kinder and gentler America.”

The younger Bush faces a more complex political challenge: building a constituency for change at a time when most Americans say they are satisfied with the country’s conditions. His answer to that riddle has been to accuse Clinton and Vice President Al Gore of squandering the opportunity these good times offer to tackle fundamental long-term problems. To make that case, Bush has been compelled to offer ambitious reform plans of his own.

Bush the younger has a second incentive for policy boldness that his father didn’t. Lacking his father’s long resume, the Texas governor from the outset has faced doubts about whether he has the smarts and experience to fill the big chair. He is unlikely to erase all those doubts by delivering speeches, but, at least in terms of media coverage, his policy offensive has submerged the overly simplistic initial tendency to portray him as a lightweight.

Still, at the heart of the difference between father and son is something larger than short-term political calculations: The agenda gap also reflects a different conception of the presidency. The minimalist campaign goals of Bush the father presaged a minimalist presidency--one guided more by a patrician instinct to “do no harm” than a burning desire to accomplish anything in particular.

Much as he respects his father, the younger Bush has made clear that he understands how much that approach contributed to the elder’s resounding repudiation in 1992. Indeed, in formulating his governing style, the younger Bush appears to have learned much more from his father’s failures than his successes. The lesson he seems to have absorbed most of all is that politicians who do not control the policy agenda inevitably find themselves responding to their opponents--at their peril.

“The concept of service is a very strong concept that was passed on from my dad’s father to him; you served,” Bush said in an interview several years ago. “I feel that as well. But on the other hand, I think you’ve got to have a reason to go into the political process. You’ve got to have a vision.”

By presenting a more elaborate vision than his father did in 1988, Bush has put himself in a stronger position to shape the campaign dialogue. But he’s also exposed himself to more risks. For starters, he’s given Gore more specifics to shoot at. “Some of the positions he’s taken will haunt him very badly,” insists one senior Gore advisor. In particular, the Gore camp thinks Bush’s large tax-cut proposal and Social Security reform plan will cause nightmares for the Republican’s campaign by November.

And by offering such an ambitious agenda, Bush has also invited not only Gore but the press to question how it all adds up within a balanced budget. How, for instance, he would fit his plans for missile defense into the relatively modest increases in Pentagon spending he’s proposed; whether he could really fund a new prescription drug benefit for low-income seniors solely out of other savings in Medicare; whether his sweeping tax cut would collide with the long-run cost of establishing individual investment accounts in Social Security--not to mention the flotilla of smaller domestic programs he wants to launch.

There’s a second generation of risk in Bush’s agenda--a governing risk. Several key items on his wish list--particularly Social Security reform and the tax cut--have relatively little appeal as currently structured to Democrats; that will make them hard to pass in the kind of narrowly divided Congress the next president is likely to face. By aiming so high in the campaign, Bush raises his risk of falling short in office if he wins.

Yet Bush clearly seems to view the greater risk as failing to drive the agenda--either as candidate or president. “Bush’s view is that it’s not like [the Democrats] are not going to shoot at us if we don’t put out these ideas,” says one advisor. “So let’s shape the playing field.”

That’s an instinct Bush’s father never possessed; it’s one reason the son is giving Al Gore all he can handle.

*

Ronald Brownstein’s column appears in this space every Monday.

*

See current and past Brownstein columns on The Times’ Web site at: https://www.latimes.com/brownstein.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.