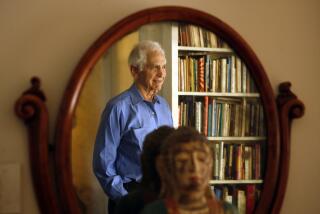

William P. Bundy; Advised President Johnson on Vietnam War

- Share via

William P. Bundy, a key advisor on Vietnam to President Lyndon B. Johnson who later conceded that the administration had made “considerable mistakes” in waging the war, died Friday at his home in Princeton, N.J.

He was 83 and succumbed to heart ailments.

As assistant secretary of state for East Asian and Pacific affairs from 1964 to 1969, Bundy encouraged a strong U.S. military presence in Southeast Asia to quell Communist-backed revolutionaries.

But by 1971, his views on Vietnam had shifted and he acknowledged failings in U.S. policy. He also urged the withdrawal of all U.S. troops.

“The issue is not whether we were right or wrong at the time the decisions were made in 1965,” he said in ‘71, referring to the debate that led to large-scale deployment of U.S. troops. “The important thing is: What should we [as a nation] be doing in the light of changed conditions?”

Bundy was, many historians say, the Johnson administration’s point man for the day-to-day management of the war, which, by its end in 1975, had cost the lives of 58,000 Americans and more than 2 million Vietnamese troops and civilians.

“His name would probably be on more pieces of paper dealing with Vietnam over a seven-year period than anyone,” wrote David Halberstam in his book “The Best and the Brightest.” “Yet he was a man about whom the least was known, the fewest articles written.”

The older brother of McGeorge Bundy, who was national security advisor to both President John F. Kennedy and Johnson, William Bundy possessed a self-assured intelligence but little of the flamboyance of his sibling.

A Democrat in a family of prominent New England Republicans, Bundy was born in Washington, D.C., where his father served as counsel to the Food Administration during World War I. Bundy earned his undergraduate degree in history at Yale and a master’s at Harvard before attending Harvard law school.

During World War II, he served in the Army Signal Corps and was a key officer in a U.S. and British operation that broke the German military codes. He later said that work was some of the most satisfying of his career.

He also got married during the war years, to Mary Eleanor Acheson. She is the daughter of Dean Acheson, who served as secretary of state under President Harry S. Truman.

After the war, Bundy practiced law, found it unchallenging and went to work for the CIA. He spent his days as an analyst, evaluating information gathered by spies.

By all accounts a man who liked to stay in the background, Bundy was pushed into the limelight in 1953, during Sen. Joseph McCarthy’s campaign to root out Communists in the State Department. McCarthy made an issue of $400 that Bundy had given to the defense fund of Alger Hiss, who was under indictment for perjury in a Communist spy case.

Bundy, who had practiced law with Hiss’ brother, defended his donation, saying: “I believed him worthy of a full defense, and the Hiss family didn’t have the means.”

Bundy was saved from McCarthy’s witch hunt by CIA Director Allen W. Dulles and Vice President Richard Nixon, both of whom strongly defended him.

In 1961, Kennedy appointed Bundy deputy assistant secretary of defense for international security affairs. In that capacity, he began regular visits to Southeast Asia. He also participated in deliberations on two crises closer to home: the bungled Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba and the deployment of Soviet missiles to that island nation.

After moving to the State Department in 1964, Bundy offered Johnson a range of ideas on Vietnam War strategy. Many of them reflected his pragmatic views.

In one, he encouraged Johnson to seek a congressional resolution giving the president some authority to conduct the war. Several months later the Gulf of Tonkin resolution was passed.

Bundy also encouraged what was termed the “swing away and bunt” strategy, by which the U.S. could fight its way to negotiations and withdrawal.

Under this scenario, the U.S. would find another Tonkin Gulf situation and use it as a pretext for a series of strong retaliatory air strikes on North Vietnam. According to Bundy’s thinking, this might cause an international crisis that could prompt a third force, such as the United Nations, to sponsor peace talks. The outcome, he believed, could be a neutralist coalition government that, while bad for Saigon, would allow a U.S. withdrawal.

Bundy’s memorandum outlining the plan was viewed with dismay by Secretary of State Dean Rusk and Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, both hawks on the issue.

From then on, the pragmatist Bundy took a centrist position, working against a full pullout but doubting that an American buildup would work. He suggested that Washington cap the U.S. troop presence at 100,000 and pressure the South Vietnamese army to perform better. But that recommendation, too, went unheeded as American troop strength rose to more than 500,000 by the time he left his position.

Bundy went on to become a visiting lecturer at Princeton in the 1980s. He was also a part-time columnist for Newsweek magazine and a trustee of Yale University. In addition, he was the editor of Foreign Affairs, an influential policy quarterly, for 11 years.

In 1998, Bundy wrote “A Tangled Web,” a critical study of the policy decisions by Nixon and his secretary of state, Henry Kissinger, that the author said prolonged the Vietnam War.

McGeorge Bundy died in 1996.

William Bundy’s survivors include his wife; children Michael of Waltham, Mass., Carol of Cambridge, Mass., and Christopher of New York City; and three grandchildren.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.