Moe Foner, 86; Union Leader Fostered the Arts

- Share via

Moe Foner, a longtime union leader whose efforts to bring the arts into workers’ lives led to his status as the Sol Hurok of the labor movement, died Thursday at his home in New York City. He was 86 and suffered from heart problems and other ailments.

Foner was for many years executive secretary of Local 1199, New York’s largest union of health-care workers. He was a key strategist in labor battles four decades ago that paved the way for organizing hospital workers in New York and across the country.

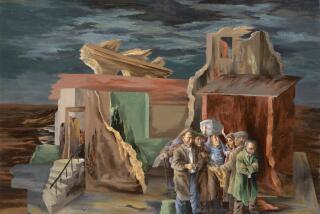

His proudest legacy was the creation in 1979 of Bread and Roses, a nonprofit cultural program with national reach that gives workers access to the arts through lunchtime theater, music and poetry presentations, films, concerts at Lincoln Center and exhibits at the only permanent art gallery run by a union.

Over several decades, he organized events with performers such as Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Sidney Poitier, Harry Belafonte, Alan Alda and Pete Seeger, often showcasing artists before they became stars. Through Bread and Roses, he also helped union members find artistic outlets, employing them as actors and authors of plays inspired by the dramas of their daily lives.

Dee, an actress and author, once said of Foner: “I’ve just not known anybody else who is so richly aware of the benefits, the joys, the necessity of arts to ordinary people.’

“The idea behind Bread and Roses is to challenge the idea that culture is elitist, somehow alien to working people,” Foner said at a December ceremony honoring him at the union’s art gallery on West 43rd Street in New York.

Foner was one of four brothers who were prominent on the American left. Philip Foner was a leading labor historian; his twin, Jack, was the author of many highly regarded books on African American history. The youngest brother, Henry, became president of New York’s furriers union.

Morris “Moe” Foner was born Brooklyn, the son of Russian and Polish immigrants. His father was a seltzer deliveryman and his mother was a homemaker. As a teenager, Foner played saxophone in a swing band with his brothers and met many musicians, actors and artists while performing at Manhattan hotels and Borscht Belt retreats.

He worked for several unions before becoming education and cultural director for Local 1199 in 1952, when it represented pharmacy employees. The union expanded its scope several years later when it sustained two long strikes and won the right to represent orderlies, laundresses and other low-paid, largely minority workers in New York hospitals.

Foner was instrumental in winning the support of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. in the union’s fight, and the two became allies in civil rights battles of the 1960s. In the 1970s, he helped mobilize labor against the Vietnam War and landed on President Richard Nixon’s enemies list.

He lost the position of executive secretary in a power struggle in the early 1980s and focused his attention on Bread and Roses. The organization ran workshops for union members that resulted in a 1980 musical about hospital workers called “Take Care” that was seen by 35,000 people in 11 states.

“He was incredibly proud of his work in creating a bridge between the labor movement and intellectuals and the arts and cultural community,” said Dennis Rivera, president of Local 1199/SEIU of the New York Health and Human Service Union, which has more than 200,000 members in New York, New Jersey and Florida. “He was a man who read a lot and who felt comfortable with poor people who had not had [the same] opportunity. He could debate philosophy with intellectuals, or hang out with artists in a bohemian setting.’

One of Foner’s last projects was a poster series called “Women of Hope” that celebrates African American, Native American, Asian American and Latina women, including Maya Angelou, Dolores Huerta and Maxine Hong Kingston. Thousands of the posters have been circulated across the country in schools, subways, airports and other public spaces. Foner initiated the project after visits to schools made him aware that the accomplishments of black women were rarely included in lessons.

“His work has helped change the way that people think of themselves in history,” said Mary Marshall Clark, director of the Oral History Research Office at Columbia University, which has preserved a series of lengthy interviews with Foner. “In various conversations I’ve had in subways and at meetings and private dinners with strong, activist women, they’ve all said how moved they were by these posters.’

Foner is survived by his wife, Anne; two daughters, Nancy and Peggy; a granddaughter; and his brother Henry.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.