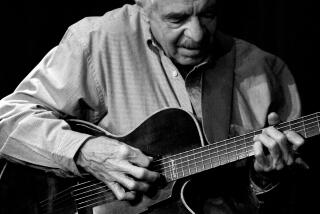

John Jackson, 77; National Heritage Fellow Was Among the Last Masters of Piedmont-Style Blues

- Share via

John Jackson, 77, one of the last masters of the so-called Piedmont style of blues singing and guitar picking, who was recognized in 1986 as a National Heritage Fellow by the National Endowment for the Arts, died of kidney failure Sunday at his home in Fairfax Station, Va. He had liver and lung cancer.

Jackson, who grew up in rural Rappahannock County, Va., never completed first grade. But he learned a library’s worth of music by ear and recorded nine albums from 1965 to 1999.

His emergence as a performer coincided with a movement to preserve the unwritten repertoire of Delta and Piedmont blues songs, which had long been played by gifted itinerant, sometimes uneducated musicians.

“I don’t read and write, and I have to keep everything right up there,” Jackson once said.

He sang for presidents and audiences around the world, from coffeehouses to Carnegie Hall in New York and Royal Albert Hall in London. The State Department sent him abroad to represent the finest in American music.

He was awarded a National Heritage Fellowship, the country’s highest recognition in the folk and traditional arts, four years after it was created.

Washington Post critic Geoffrey Himes was impressed with the mastery Jackson displayed on his final release, “Front Porch Blues” (Alligator Records).

“Like many an older artist,” Himes wrote, “Jackson has pared away all the unnecessary notes to reveal the essential dialogue between his gravelly baritone voice and his sparkling, skeletal guitar lines.”

For all his acclaim, Jackson continued to work as a part-time gravedigger and never saw music as a full-time occupation.

He might share a bill with Pete Seeger and the Carter Family one weekend and return to the graveyard on Monday.

Jackson grew up on a farm, the seventh of 14 children. His parents were amateur musicians, but he credited a chain-gang convict he knew only as “Happy” with his earliest guitar training.

As he grew older, Jackson was invited to play at local gatherings. A violent fight at one country party, at which a man accused Jackson of stealing his guitar, turned him off to music for years, as did an increased demand for rock ‘n’ roll. He eventually became caretaker of Fairfax City Cemetery.

He had long forsaken his musical ambitions, he said, when a bunch of bored children wandered by one day and asked Jackson to entertain them with a song. Soon he was giving lessons in the back room of a gas station.

Charles Perdue, a government employee who had just helped start the Folklore Society of Greater Washington, stopped at the service station one day in 1964 and saw Jackson with the guitar.

He coaxed the musician to play Mississippi John Hurt’s “Candy Man” and was immediately struck by his precise rendering of the complex piece. Perdue persuaded Jackson to play at the old Ontario Place in Washington, where record label officials often caught top local acts.

Chris Strachwitz, whose California-based Arhoolie label became a force in roots music, heard one of Jackson’s performances and decided to record him.

They went to Jackson’s home and taped him for 11 hours; Strachwitz paid the musician $150.

A year later, “Blues and Country Dance Songs From Virginia” came out.

But Jackson said he never made enough money from his songs to quit grave digging.

Survivors include three sons, a daughter, seven grandchildren, five great-grandchildren, a sister and two brothers.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.