Slipping the Knots to Fame

- Share via

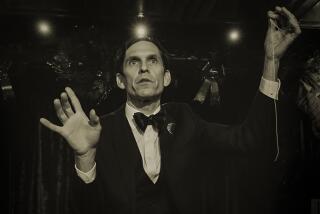

Mark Cannon needs a new challenge. He’s already been strapped into a straitjacket and dangled from a hot-air balloon. He’s been stuffed into a mailbag, cuffed at the wrists and ankles, and then tossed into a swimming pool. He’s survived a wall of spikes that slammed down on his fully restrained body.

Cannon could try the famed milk can escape perfected by his role model, the legendary Harry Houdini, but, frankly, it has become a bit quaint.

“I’m always looking to take things to the next level,” Cannon said recently as he puttered around his Yucaipa garage-studio, where he builds water submersion cells, neck collars and one-of-a-kind leg irons.

At first glance, Cannon looks nothing like a master of escape. By day, the father of two flies a Cessna T-206 as a California Highway Patrol sergeant looking for speeders and other lawbreakers in Riverside, Imperial, Orange and San Diego counties.

But during his off hours, Cannon escapes into his art, whether it’s wiggling out of a pillory or selling a compatriot a new Gimmicked Posey Roller Buckle Strait Jacket with Belly & Side Loops.

Cannon’s home in San Bernardino County’s foothills, about 75 miles east of downtown Los Angeles, has become a hub for the resurgent world of escape artists, whose skills are in demand thanks to daredevil reality shows, extreme sports and graphic video games. He and his wife, Sheila, run an Internet-based catalog company offering the latest in submersion devices, thumbscrews, shackles and lock picks. Hundreds of aficionados also use the site to swap tales and advice.

For decades, escape acts took a back seat to big-name magicians and illusionists such as David Copperfield and Lance Burton.

Now the true masters of the art of escape are slipping out of obscurity.

Michael Griffin, one of the country’s top escapists, is negotiating with a Hollywood production company on a TV show that would follow him as he overcomes his own fears, setting up improbable escapes from sealed coffins or being tossed into ice-encrusted rivers wrapped in restraints.

“Every human being fears death,” said Griffin, who plans to move from Ohio to Southern California next fall to pursue the show and other ventures. “I tap into that fear.”

Audiences also want to be diverted from war, terrorism and a sour economy, and what better escape is there than, well, an escape? Everybody can identify with the escape artist, Cannon said, because “all people have an inner desire to escape from something in their lives.”

Until the Cannons founded their company in 1999, the craft’s gear and equipment was difficult to find and escapists had no associations or major venues to call their own. During the last four years, Cannon’s mailing list has grown to more than 1,350.

Last April, his company sponsored its first Escape Artist Convention in Indianapolis, appropriately held in conjunction with a nationwide locksmith show.

The gathering attracted more than 130 enthusiasts, who networked, performed and browsed exhibits offering antique handcuffs, leg irons and other equipment, with prices ranging from $1 for a small padlock to $5,000 for a one-of-a-kind 18th century lock.

Griffin was presented a “Silver Cuffs” award for professional dedication. An Australian master locksmith lectured on “Fundamentals of Lock-Picking.”

Indiana’s Kristen Johnson became the first female to perform a vertical escape from a narrow, 6-foot, 4-inch-tall water-filled tank. Restrained with handcuffs, a neck shackle and leg irons, she freed herself in full view of onlookers.

Johnson proclaimed the convention to be “a milestone for the escape community,” which has been in something of a funk since Houdini’s death on Halloween Day in 1926 at the age of 52.

Considered by many as the country’s first entertainment superstar, Houdini died of a ruptured appendix after he was struck unexpectedly in the abdomen by a student who thought he had been invited to test the celebrity’s muscles. During his career, Houdini ruled the world of escapists and bequeathed his trade secrets only to his wife, brother and select assistants, according to historians of the craft.

The proliferation of reality TV shows in recent years, with their freaky and frightful gimmicks, has helped rekindle interest in escapology. But no performer has ever come close to Houdini, said Penn Jillette of the illusionist duo Penn & Teller.

“Houdini is a conceptual idea,” Jillette said. “Houdini called himself a self-liberationist, not an escape artist.”

Despite Houdini’s exalted status, a bias exists against escapists. Some argue that they’re not magicians, including the top staff at Magic, the Magazine for Magicians. The Las Vegas-based industry bible chooses to bypass most escape coverage.

Escapists rarely perform at the Magic Castle, a private clubhouse for the worldwide Academy of Magical Arts in Hollywood.

“It’s not magic,” said a retired magician who works for the 5,000-member group. “They are slow, they wiggle, they squiggle, and everyone knows they’re going to escape.”

Cannon, one of the few escapists who has performed at the Magic Castle, argued that escape belongs in the magic genre because acts include fundamentals such as sleight of hand, mystery and illusion.

And like a true magician, escapists never, ever reveal their trade secrets. Of course, Web sites, books and television shows do.

Some escapists use trick handcuffs and straitjackets. Others, including Houdini, apparently regurgitated keys or hid rivets, springs, strings and other tools in secret compartments to pick locks.

Some tricksters argue that no two secrets are alike, so it’s impossible to offer an explanation. Others, like Cannon, believe it’s uncouth to discuss such matters among non-magicians.

Cannon staged his first escape while in high school in Yucaipa, submerging himself in a locked 55-gallon drum of water for more than two minutes.

He almost didn’t make it. A bumbling locksmith, who provided the padlock for the drum, tried to help Cannon’s assistant and ended up delaying the escape.

“Unfortunately, like a lot of kids, I did not realize the danger involved,” Cannon said. Escape involves taking calculated risks, weighing everything that could go wrong, assuming that it will, and relying on skills and wisdom built from years of practice, Cannon said. “Unlike other magic tricks, you can die if you make a mistake,” he said.

At least a dozen people have died over the years trying to imitate Houdini’s milk can caper -- his signature act in which, bound by chains and handcuffs, he would escape from a padlocked steel milk can filled with water.

Cannon has faced two additional life-threatening mishaps. In 1982, the “Spike Cabinet of Death,” his own invention, nearly nailed him during a cruise ship performance in the Bahamas when the boat suddenly pitched, prematurely triggering the descent of two dozen 10-inch spikes. Cannon, tied and locked up, managed to roll out just as the top slammed shut. One spike punctured his right shoe, narrowly missing his foot. The audience erupted in applause.

Cannon said the cruise director asked him to “leave the shoe part in during your next act.”

His second close call also occurred on a cruise ship, this time while crammed into a locked mailbag and thrown into the vessel’s saltwater pool. The seawater corroded the lock. Cannon also had forgotten the Swiss Army knife he usually hid inside his swim trunks as an emergency backup.

Cannon squirmed inside the thick canvas bag, which was secured with padlocks in its metal grommets. His adrenaline pumped so hard that he was able to rip the seams.

The crowd, unsuspecting of the danger, loved it.

“Escape is about facing your own mortality and conquering it,” said Cannon, who says the adrenaline rush is one of the main reasons he got hooked.

He and his wife run their business out of their home, decorated in casual country-meets-torture chamber style. A lacy angel wall-hanging hovers near a Colonial pillory. A book on quilt patterns leans near a prison ball and chain. Gauzy material lies near Cannon’s steel straitjacket with its side hinges, padlocks and wrists that lock to the belly.

In the office, where Sheila oversees the computer work, packing and shipping orders, the couple’s collection of more than 200 restraints dangles from the white walls. Straitjackets hang in a closet.

The company sends out so many packages that a mail delivery company employee dubbed the sweet, soft-spoken Sheila “The Straitjacket Lady.”

Neighbors know the Cannons well enough to think nothing of waving hello to them as they spend a lazy Sunday afternoon building a guillotine in the garage.

Prisoners sometimes pester the Cannons, trying to buy items on the Web site. But Cannon built safeguards into the system. To make a purchase, a person must present evidence of law enforcement affiliation, a locksmithing license or affiliation with a credible magic organization.

“We make sure not to deal with the people from San Quentin,” Cannon said.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.