The tempest over his teapots

- Share via

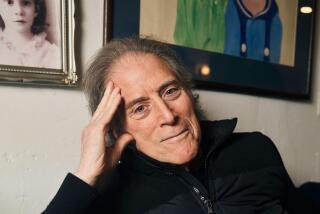

LONDON — Richard Curtis: saint or sinner?

Richard Curtis: savior of modern romantic comedy or dispenser of treacly, farfetched fantasy?

Richard Curtis: the best thing to hit the British film industry in decades? Or one who panders to American tastes?

Bet you didn’t realize there was such a hot debate.

In truth, there isn’t unless you live in Britain. Here, the arguments about Curtis’ virtues and weaknesses have exercised the minds of London’s chattering classes for the last few weeks. In the broadsheet press, long deliberations over the significance of Curtis and what he stands for have threatened to eclipse real news, including the Iraq conflict and the controversy over U.S. President Bush’s recent state visit to Britain.

This outbreak of strongly held opinions has coincided with the U.K. release of Curtis’ latest film, “Love Actually,” which he wrote and directed (it opened about a month ago in the States). His earlier successes, all romantic comedies, were solely as a screenwriter: “Four Weddings and a Funeral” (1994), “Notting Hill” (1999) and “Bridget Jones’s Diary” (2001). All were international hits, and “Four Weddings” established Hugh Grant as a global box-office star. Curtis, meanwhile, has become that rare creature: a screenwriter with a globally recognized brand.

So what is it about his films that his detractors find so dismaying? In a nutshell, they claim he peddles a false picture of British life to the rest of the world. This objection recurs repeatedly. A recent sour (and anonymous) profile of Curtis in the Sunday Telegraph complained that “Love Actually” was “set in an England we can hardly recognize.” Sunday Times essayist Bryan Appleyard sniped: “Plainly Curtis knows something I don’t. His London is not remotely like mine.”

Both writers used the term “Curtisland” (originally coined approvingly by arts journalist Sarah Crompton) pejoratively, to denote the universe portrayed in his films. “Curtisland,” sneered the Sunday Telegraph, “has no housing [projects], muggings, drug addicts, handguns, road works or Tube delays. Everyone travels by black taxi and boasts a delightfully acerbic gaggle of loyal university chums.”

Well, gosh (as Grant’s characters in Curtis films tend to say), so these romantic comedies aren’t more like gritty documentaries. It’s an odd argument, to say the least. “Love Actually” features nine intertwining love stories, most of which end happily. One involves a British prime minister (Grant) falling in love at first glance with the young woman who brings him a cup of tea each morning. You might regard this as a tip-off that disbelief was to be suspended for a couple of hours.

Did anyone ever complain that Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers films lacked bite? In dozens of classic film musicals and comedies, from Busby Berkeley to Woody Allen, characters lived in the opulent glamour of New York penthouse apartments; perpetually in evening dress, they rattled off witty repartee without pause or stutter. I can’t recall critics whining that no one really lived like that.

Another charge against Curtis is that he romanticizes the beauty of England, especially London and the river that runs through it. Here is the British film magazine Sight & Sound: “Curtis’s scenic Thames shots ... seem to be his picture-postcard love letter to the U.S. audiences his films have always aspired to impress.”

What an outrage, huh? A British filmmaker with the gall to extol the loveliness of his capital city. Can you imagine anyone telling Jean-Luc Godard or Francois Truffaut not to make Paris look so damned captivating? Or Allen’s producer urging him to tone down “Rhapsody in Blue” on the “Manhattan” soundtrack, in case audiences were blown away by New York’s splendors?

Curtis has done nothing to bring this on himself. In person he is affable, courteous and self-deprecating. All his colleagues gush about his niceness; if he has personal enemies, they have yet to come forward. He’s even philanthropic; in the 1980s he co-founded the charity Comic Relief, and he remains its vice chairman. It has raised more than $550 million for charity projects.

Yet somehow Curtis and his works truly irritate hand-wringing commentators. At first glance, their complaints seem disproportionate: One may not like “Love Actually,” but undeniably it’s a well-crafted entertainment, and everyone in London knows far inferior British films open here regularly. So why the spluttering rage?

Here’s a clue. It was clear for weeks before its release that “Love Actually” would be a massive hit, and so it has proved. The film’s opening weekend gross was around $11.3 million, a huge amount by British standards. This suggests that “Love Actually” will join Curtis’ three earlier films among the half-dozen most successful ever made in Britain.

Which brings us to an unlovable trait that flourishes in London, known as “tall poppy syndrome.” We British like our talented people to be moderately successful, but if they are acclaimed abroad (especially in America) we tend to turn on them. The combative British press embodies this trait perfectly.

The problem is intensified by the state of the British film industry, which without Curtis and the output of his colleagues in the production company Working Title would barely exist. The industry enjoyed a resurgence in the ‘90s, with hits from Curtis’ pen as well as films like “Trainspotting” and “The Full Monty,” but it has now returned to its default mode: That is to say, it is in a slump.

So when a rare potential global hit like “Love Actually” comes along, it labors under enormous expectation and analysis. The media here fret about how every home-grown hit presents Britain to the rest of the world.

Other theories have been advanced to explain why Curtis finds himself at the center of controversy. One is that he is not afraid to portray sentiment, and Britain’s educated classes have a problem with sentiment. (I know film critics in London who literally cover their eyes at screenings when a poignant moment arrives on screen.)

The other theory revolves around class. Curtis (an Oxford graduate) creates the sort of characters he knows -- upper-middle class, privileged, unencumbered by dull jobs. Some critics in Britain find these characters complacent and shallow and are infuriated by their endless joviality. Yet many critics come from precisely that background; it may be that Curtis irritates them because he holds up a mirror to their lives.

You want to tell them: Lighten up, guys. Curtis’ comedies are benign confections that send millions of people out of theaters with big smiles on their faces. They’re not meant to be taken too literally, and here’s proof: in “Love Actually,” Grant administers a stern public rebuke to Billy Bob Thornton, playing a visiting U.S. president. A British prime minister standing up to the man from the Oval Office? Fantasy, pure fantasy.

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.