Judge Declares a Mistrial in Quattrone Case

- Share via

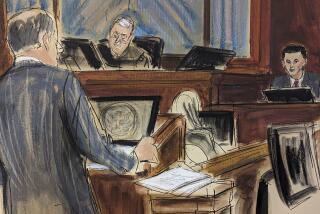

NEW YORK — One of the first criminal trials to stem from corporate America’s recent scandals ended in a mistrial Friday after a jury deadlocked over whether former Silicon Valley financier Frank Quattrone tried to block government probes of new stock offerings.

The outcome of the closely watched proceeding represented a stinging defeat for federal prosecutors, raising questions about how the government would fare in coming trials of other white-collar defendants and whether Quattrone would face a retrial.

Quattrone had been charged with two counts of obstruction of justice and one count of witness tampering.

In the jury’s final vote Friday, the tally was 8 to 3 in favor of conviction on one obstruction count and on the tampering count, one juror said, and 6 to 5 for acquittal on the remaining count.

The final votes belied what appeared to be sentiment for acquittal through most of the deliberations. The first jury vote last week was 7 to 4 in favor of acquittal, and remained 6 to 5 for acquittal on all counts until Friday, the juror said.

The deep division on the jury seemed to indicate that ordinary Americans were less willing to convict corporate executives than had been assumed, analysts said. That could have implications for the government’s broad crackdown on white-collar crime by making prosecutors reluctant to press such cases while emboldening corporate defendants to fight charges rather than agree to plea bargains.

“It is going to roll back some of the momentum in prosecutions like this,” said Warren L. Dennis, a white-collar defense partner at Proskauer Rose in Washington. “Prosecutors around the country do not want to see their names in the paper with this outcome.”

The Quattrone outcome could have the most immediate effect on the defense strategy of home-design entrepreneur Martha Stewart, who is scheduled to stand trial in mid-January on obstruction and other charges. Like Quattrone’s, the case against Stewart is viewed as tough to win.

“The champagne is flowing in Martha Stewart’s lawyer’s office,” said George B. Newhouse Jr. of Thelen Reid & Priest in Los Angeles. “She’s going to get a similar jury in a similar case, and it will present for the prosecution a similar set of problems.”

Quattrone declined to comment, but his attorney, John Keker, said outside court that he was disappointed at the hung jury. “Frank is innocent,” Keker said. “Frank Quattrone is a man of integrity and a man who followed the rules.”

Nevertheless, experts said Quattrone’s team probably was thrilled because anything other than a conviction is viewed as a victory for a defendant.

“He rolled the dice and he won,” said Stephen M. Ryan, a former prosecutor who is now a partner at Manatt, Phelps & Phillips in Washington.

Prosecutors refused to comment.

The trial lasted four weeks and deliberations ran about 4 1/2 days. A mistrial had been expected since last week when jurors first told U.S. District Judge Richard Owen they were deadlocked. Prosecutors will return to court Nov. 5 to discuss with Owen whether they will retry Quattrone.

Lead prosecutor Steven Peikin said earlier in the trial that they probably would bring a second case, but some experts said the jury’s skepticism coupled with the potential embarrassment of faltering a second time could sway prosecutors against a retrial.

Had he been convicted on all counts, Quattrone would have faced a sentence of as much as 25 years in prison, although he probably would have been sentenced to considerably less under federal sentencing guidelines.

Quattrone, 48, was Silicon Valley’s premier investment banker throughout the late-1990s technology boom and became one of the most powerful men on Wall Street by bringing public such powerhouse companies as Cisco Systems Inc. and Amazon.com Inc.

In some ways, Quattrone was an unlikely figure to excel on Wall Street. His father was a garment worker and union representative, and Quattrone went to college on scholarship.

The case against Quattrone was largely circumstantial, revolving around a brief e-mail he wrote to his staff in December 2000. The two-line missive encouraged his subordinates to comply with an e-mail sent by another banker a day earlier urging them to clean up their files.

Prosecutors said Quattrone had been trying to prod his technology banking team to destroy documents sought in investigations by the Securities and Exchange Commission and a federal grand jury. Those probes centered on whether his former firm, Credit Suisse First Boston, forced customers to pay outsized commissions -- basically kickbacks -- for shares of hugely profitable initial public stock offerings.

But there was no conclusive testimony or evidence that Quattrone had tried to block the federal investigations. The heavy reliance on the single e-mail left the jury feeling the government hadn’t proved its case, one juror said.

“There was no really hard evidence,” said Mayo Villalona, 27, a bank employee from Manhattan. “It was a two-line e-mail and it was empty.”

Frequently, obstruction cases involve repeated actions, such as the shredding of documents over an extended period.

Prosecutors labored to prove that Quattrone had known about the probes and considered them a threat to his Palo Alto-based tech banking empire. The most damaging evidence came when a former CSFB lawyer testified that he told Quattrone that the financier could become involved in the grand jury probe a mere eight hours before Quattrone sent his e-mail.

Prosecutors tried to use Quattrone’s success against him, at one point interrupting testimony from their own witness to tell jurors that Quattrone had earned as much as $120 million in a single year.

Quattrone’s defense hinged on his repeated insistence that he had not been responsible for allocating IPO shares to investors, and thus had no motivation to obstruct the IPO probes.

A key moment came when Quattrone took the risky step of testifying on his own behalf. The move backfired when Quattrone admitted under grueling cross-examination by Peikin that he was involved in some IPO allocations -- contradicting the defense’s attempts to portray Quattrone’s role as hands-off.

During his cross-examination, Quattrone frequently parsed his answers, forcing Peikin to admonish him to answer his questions. That struck some jurors as evasive, and Quattrone may have been acquitted if he had not taken the stand, Villalona said.

“He did a bad job going up there,” Villalona said. “A lot of jurors said if he had not gone up there he would have been [found] not guilty on the spot.”

The trial was marked by repeated clashes between Keker and Owen, an 81-year-old jurist known for a pro-prosecution bent who repeatedly ruled in favor of the government.

Quattrone’s legal troubles are not over. He is under investigation by New York Atty. Gen. Eliot Spitzer. He also is fighting charges from the NASD, which regulates the securities industry.

Under the terms of his contract with CSFB, the securities firm is paying Quattrone’s legal bills. He will have to reimburse the firm if he is proved to have committed wrongdoing.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.