Talk of the U.S.

- Share via

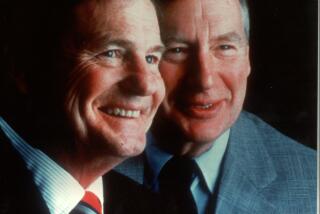

In his latest PBS special, veteran newscaster Robert MacNeil poses the question: “Do You Speak American?” The three-part series, which explores the history, diversity and evolution of the American language, is a follow-up to the 73-year-old MacNeil’s award-winning 1986 documentary, “The Story of English.”

In “American,” which airs Jan. 5 on KCET, MacNeil travels the country, focusing on language controversies such as bilingualism, Ebonics and political correctness.

During his visit to Los Angeles on the show, he chats with screenwriter-director Amy Heckerling (“Clueless”) about Hollywood’s influence on our language and encounters surfers and skaters up the coast who “translate” their own dialect for MacNeil.

The recipient of numerous broadcasting awards, MacNeil has penned several books, including “Looking for My Country.”

Was there ever a section of the country that was considered the best example of American English?

Most people consider, whether they be from the South or New York or anywhere else, when they are asked, “Where do you think the best American English is spoken?” they usually say the Midwest. The Midwesterners pronounce their Rs -- coming out of Philadelphia with the Scots-Irish influence. English people who didn’t pronounce their Rs settled the other Eastern cities.

There is an interesting ideological component in that admiration for the Midwest. At the turn of the century two things happened: The Western frontier disappeared. It is a big psychological moment in American history -- the idea of unlimited space stopped. And at the same time, there was a huge migration from Europe into the Eastern cities, including many Catholics and Jews.

Harvard, which had been admitting before the first World War 6% Jews, found itself admitting 22% [after the war] and felt it was a crisis. They appointed a faculty committee to strengthen their admission procedure. They came up with the conclusion they should recruit from the Midwest -- this Christian Nordic type. Other universities caught on to this.

Is the Midwest thought of the same way now?

What you can say now is that the speech of the Midwest has kind of been codified in the American imagination as the sort of representative of American speech largely because it was adopted by broadcasters in the early days of broadcasting. The NBC handbook of pronunciation and its equivalent at CBS, which were published in the 1930s, were very big on this accent because it was free of regional identifiers, which were regarded as negative. Broadcasters still look for an accent that is not so loaded with regional identifiers that would be unattractive to some people somewhere.

Ronald Reagan was an absolutely perfect example [of the Midwest accent], coming out of Illinois.

But one of the most popular presidents, Franklin D. Roosevelt, had a very distinct accent.

Roosevelt was representative of sort of the anglophiles’ pronunciation that was an upper-class standard in the East up until the second World War and then it stopped. A lot of movie actors and stage actors adopted this Cary Grant way of talking. We have a piece in the documentary with Roosevelt giving [a] fireside chat using words like “fear,” which he pronounces as fe-ure.

Suddenly after World War II, just when you thought the prestige of the British would have been at its pinnacle [because they were our allies], America turned against that; you can see in New York, which was an R-less city. At the rate of about half a percent a year, New Yorkers are finding it socially prestigious to drop that R-less pronunciation and adopt the R, which is happening in the South too.

Before the great migration of rural Southern African Americans to the North in the 1930s and ‘40s, white Americans and black Americans’ speech was very similar.

They were speaking very similarly because they mingled a lot, like in general stores. After the great migration north by the blacks, blacks became much more separated from whites.

As they became more isolated their language became more different.

Ebonics plays a major part in the documentary.

We go into history of Ebonics with the court case in Ann Arbor [in Michigan] back in the 1970s -- where a federal judge ruled that a school was discriminating against black kids because of the way they spoke and the teachers regarded them as uneducable -- to the Ebonics controversy in Oakland in the 1990s and on to schools in Los Angeles, where in the last 10 years, 60 schools within the Los Angeles consolidated school district have been experimenting with fifth-grade classes that teach kids the difference between African American English and standard American English.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.