An Effort to Shift the Focus to the Other Guy

- Share via

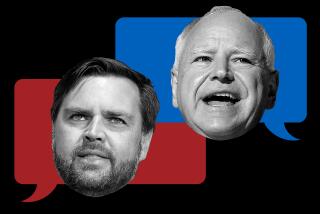

WASHINGTON — In a spirited and at times fierce debate, Vice President Dick Cheney and Sen. John Edwards made it clear that both presidential campaigns believed this election could turn on a single question: Will the race be more about the record of George W. Bush or that of John F. Kerry?

Tuesday’s 90-minute encounter was far more intense and confrontational than Cheney’s relatively genteel debate with Democratic vice presidential nominee Joe Lieberman in 2000. At times it felt like a heavyweight bout, in which each fighter was landing teeth-rattling blows against the other.

But behind the heated rhetorical battle, a clear strategy emerged on each side -- one that signaled the two campaigns’ broader goals in the election’s final month.

The two men continued the tug of war that is increasingly shaping the campaign’s final turn. During August and September, both sides agree, the Bush campaign succeeded in focusing the campaign on whether Kerry was strong and steadfast enough to serve as president; in last week’s first presidential debate, Kerry succeeded in at least temporarily shifting the focus back to Bush.

Throughout the debate, Cheney repeatedly targeted Kerry’s and Edwards’ Senate records, arguing that they invalidated the pair’s claims that they can protect the country in the age of global terrorism. Revealing an increasing emphasis for the Bush campaign, Cheney went beyond the familiar charge that Kerry had flip-flopped on issues, repeatedly challenging the Democrat’s underlying positions.

Edwards, who may have been even more relentless than Cheney about pressing the offensive, constantly sought to turn the focus back to the record of the Bush-Cheney administration. Signaling an increasing Democratic priority, Edwards was especially dogged in charging that Bush and Cheney had misled the country, especially on Iraq.

Cheney’s unstinting attacks on Kerry’s voting record -- not only on national security but on taxes and even medical liability reform -- dramatized the priority the Bush campaign placed on moving the spotlight back onto Kerry; that emphasis is likely to be apparent again today when Bush delivers a major speech that sources say will broaden his critique of Kerry’s record.

But Edwards cheered Democrats with a sweeping indictment of Bush’s record -- not only on Iraq but on domestic issues such as the deficit, job creation and healthcare -- that probably previewed the arguments Kerry intended to stress in the next two presidential debates.

Indeed, each man may have crystallized his side’s case against the other more sharply and concisely than their principals did in the presidential debate last week. Cheney seemed somewhat defensive and rigid at the outset, but he quickly settled into a presentation that was confident and forceful, though without the humor that leavened his appearance against Lieberman.

Edwards, who faced criticism earlier in the campaign from some Democrats who thought he wasn’t delivering a sharp enough case against Bush, was just as forceful. He took the offensive from the opening bell, when in his first substantive remarks of the debate he declared, “Mr. Vice President, you are still not being straight with the American people.” As the evening proceeded, Edwards met each Cheney charge with a charge of his own.

The debate lost some momentum in its final half-hour as the questions drifted from the central issues in the campaign and the two men seemed to sag a bit; to extend the ring metaphor, they seemed like fighters whose arms were tired from throwing so many punches.

“I thought the fire went out of both of them when it came to domestic issues,” said Andrew Kohut, director of the Pew Research Center for the People and the Press, a nonpartisan polling organization. “There just isn’t the emotional level when you are talking about prescription drugs or healthcare as compared to Iraq and the war on terrorism.”

But in the first hour, Edwards and Cheney clashed unstintingly, engaging in exchanges more heated than anything between Kerry and Bush last week.

The two offered a stark contrast in style. Cheney held his hands so closely in front of his face that he sometimes muffled his microphone; Edwards often punctuated his words with emphatic gestures.

For much of the evening Cheney watched Edwards with a look of predatory bemusement, reminiscent of a cat eyeing a canary. Edwards generally veiled his emotions more, though when Cheney said that Edwards was disparaging the sacrifice of Iraqi soldiers in the war there, the senator shot him a look that might have drawn the Secret Service onto the stage had it occurred in another context.

Inevitably, the two men challenged each other personally. Edwards attacked Halliburton, the giant corporation that Cheney headed before his election, and denounced Cheney’s voting record in the House. Cheney accused Edwards of dodging taxes as an attorney and belittled his record in the Senate; in one of the evening’s most dramatic moments, Cheney declared that in his role as presiding Senate officer, he had never even met Edwards until the debate. (After the debate, the Kerry campaign released a photo and transcript that apparently showed Cheney had greeted Edwards at a National Prayer Breakfast.)

Yet these were relatively brief detours in a debate whose principal function was to rehearse and advance the arguments each of the presidential candidates intended to wield against the other in the campaign’s final weeks. Heading into the debate, senior strategists for both sides said their principal goal for the evening was to drive the exchange toward the record of the other side.

Both campaigns agreed with veteran Republican strategist William Kristol, who served as chief of staff for Vice President Dan Quayle, when he said, “Cheney’s task is not to defeat Edwards in the debate; it’s to do damage to Kerry, and the same for Edwards on the other side.”

In that effort, the personal arguments between the two men -- over Halliburton or Edwards’ attendance record -- were largely tangential. Instead, they devoted most of their energy to making the case for the man on the top of their ticket; Edwards even turned a question about his credentials into a tribute to John Kerry’s qualifications.

An ABC News instant poll showed that viewers preferred Cheney over Edwards by 43% to 35%, with 19% considering it a tie. A CBS panel of undecided voters gave Edwards the edge.

But traditionally, the vice presidential debate has not heavily influenced the trajectory in the presidential race, and Tuesday’s session did not produce a result so decisive that it was likely to break that pattern.

The evening’s real significance is likely to be felt in the extent to which it advanced arguments that will resonate in the contest between the principal protagonists, Bush and Kerry.

Some senior Republicans said after the debate that they believed Cheney, like Bush last week, had allowed too many Democratic charges to go unanswered. But Cheney was far more diligent than Bush last week in challenging Kerry’s voting record in the Senate, particularly on national security.

“A little tough talk in the midst of a campaign, or as part of a presidential debate, cannot obscure a record of 30 years of being on the wrong side of defense issues,” Cheney insisted.

Edwards may have revealed the most about coming Democratic strategy in his attacks on the administration’s honesty and credibility, especially over Iraq, and in his closing statement.

In last week’s debate, Kerry said Bush, in effect, was promising Americans “more of the same” in Iraq if reelected. On Tuesday, Edwards broadened that refrain into an indictment of the administration’s domestic record as well.

“What they’re going to give you is four more years of the same,” he said in his closing remarks. “John Kerry and I believe that we can do better.”

With those arguments, the two reduced the race to what may be its essence. One side is warning of the risks of change; the other of the hazards of continuity. The debate between Cheney and Edwards probably won’t do much to decide this contest. But it did sharpen the argument that probably will.

More to Read

Get the L.A. Times Politics newsletter

Deeply reported insights into legislation, politics and policy from Sacramento, Washington and beyond. In your inbox twice per week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.