Former Enron Employee Describes Scheme

- Share via

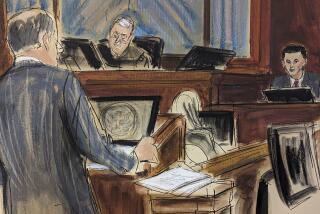

HOUSTON — As Enron Corp. scrambled to unload its interest in several Nigerian power-producing barges in December 1999, former finance chief Andrew S. Fastow contemplated coming to the rescue with a buyer he created so he would be a hero to then-President Jeffrey K. Skilling, Fastow’s former top aide testified Monday.

In the first criminal trial to emerge from Enron’s December 2001 crash, the aide, Michael Kopper, said he had considered it a risky deal for Fastow’s LJM2 partnership, even though Fastow said it would help Enron and “he would look like a hero to Jeff Skilling.”

Enron’s then-treasurer, Jeffrey McMahon, however, was enlisting Merrill Lynch & Co. to buy the interest in the barges and allow Enron to book a $12-million pretax profit at the end of 1999. Merrill Lynch came through.

But Kopper, in a calm voice, acknowledged that he and Fastow skimmed millions of dollars from Enron through myriad other schemes, some of which helped fuel the company’s implosion.

Kopper is a key witness in this fraud and conspiracy trial of four former Merrill Lynch executives and two former mid-level Enron executives.

He pleaded guilty more than two years ago to two counts of conspiracy -- becoming the first ex-Enron executive to admit to committing crimes -- for his role at the center of financial schemes Fastow orchestrated. Kopper’s cooperation paved the way to Fastow, who in January this year pleaded guilty to two counts of conspiracy.

Kopper called Fastow, his former boss, both brilliant and “very greedy,” noting Fastow pocketed more than $45 million in ill-gotten money while Kopper raked in about $16 million.

Kopper said he had enticed his domestic partner to invest in some of Fastow’s shady deals. Kopper negotiated a plea bargain and his partner secured a deal to avoid prosecution.

Kopper acknowledged Monday that he hoped his cooperation and testimony might spare him prison altogether. He faces anywhere from probation to 15 years in prison when he is eventually sentenced.

Skilling, who has pleaded not guilty to conspiracy and fraud charges in a separate case, was Fastow’s boss at the time of the barge deal.

Skilling’s lead attorney, Daniel Petrocelli, said the barge trial and Kopper’s testimony demonstrated that Enron prosecutions “are about the crimes and more crimes and more crimes of Andy Fastow” and others who cut deals with the government “to convict innocent people.”

The government contends that the six people now on trial knew that the sale was a sham because Fastow had promised that Enron would find another buyer or buy Merrill Lynch’s interest itself within six months. The defendants contend that the energy company was never obligated to buy back the barge equity.

“If they were sold in December there should have been no reason for LJM to purchase them in June [2000],” Kopper testified.

And LJM’s time would come, he said. In June 2000, Fastow called Kopper -- who was a managing director both for LJM and Enron -- and “kind of giggled” about LJM’s buying Merrill Lynch’s interest in the barges.

Kopper said Fastow told him McMahon had promised Merrill Lynch that Enron would ensure the brokerage’s barge interest would be bought out in six months, and Enron needed to follow through to maintain stature in the marketplace as a company that kept its word.

LJM2 stepped up, but Kopper said the partnership got a promise of its own to be bought out by January 2001. He said Fastow secured an agreement that Enron would buy LJM’s interest if another buyer wasn’t found. LJM bought Merrill Lynch’s interest. Later in 2000 AES Corp. bought the barges from Enron, culminating a deal that had been in the works.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.