Smallpox Exercise Poses Big Question: Is Anyone Ready?

- Share via

WASHINGTON — At 9:03 a.m., a TV broadcast reported an outbreak of smallpox in four European countries, and a terrorist group tied to Al Qaeda claimed responsibility for spreading one of history’s most dreaded diseases.

By midafternoon, as the president of the United States and leaders of major Western nations struggled to contain a cascade of horrors, authorities confirmed 3,320 smallpox cases across the globe. They warned of 660,000 potential victims, major political upheavals and a collapsing world economy in the weeks ahead.

That was the fake but terrifying scenario played out in a darkened hotel ballroom here Friday by former U.S. Secretary of State Madeleine Albright and 11 senior European diplomats and politicians. For seven hours, they grappled with a grim tabletop exercise that fused fact and fiction to help educate government officials about the growing threat of bioterrorism.

“The scenario we posited is very conservative,” Tara O’Toole, head of the Center for Biosecurity at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, said at the close of the privately funded $250,000 session. “This could have been much worse. The age of engineered biological weapons is here. It is now.”

The CIA agrees. The National Intelligence Council, the CIA’s in-house think tank, warned in a report Thursday that terrorists were more likely to obtain and use pathogens and pestilence than nuclear weapons to cause mass casualties in the next 15 years.

The council based its assessment on dramatic advances in genetic research and biotechnology, the availability of scientific information and supplies on the Internet, and the emergence of sophisticated terrorist “groups, cells and individuals” who may be “particularly suited” to brewing lethal germs at home.

“Indeed, the bioterrorist’s laboratory could well be the size of a household kitchen, and the weapon built there could be smaller than a toaster,” the council wrote. “Terrorist use of biological agents is therefore likely, and the range of options will grow.”

Because incubation periods typically can be measured in days or weeks, the report added, “an attack could be well underway before authorities could be cognizant of it.”

Since the Sept. 11 attacks, the Bush administration and Congress have poured billions of dollars into programs to upgrade security and develop vaccines to prevent or control epidemics. But critics say far more needs to be done to counter potential bioterrorism.

Indeed, obtaining lethal germs and toxins still appears surprisingly easy in the U.S.

On Wednesday, for example, authorities in Ocala, Fla., arrested a 22-year-old man after they allegedly found the deadly toxin ricin, which is derived from castor beans, in a cardboard box at his home. In April, a 37-year-old man in Kirkland, Wash., similarly was charged with possession of home-grown ricin after he allegedly threatened to poison local water supplies.

Last Monday, a federal judge in Fort Lauderdale, Fla., ordered the recall of several thousand vials of botulinum toxin, one of the most poisonous substances known, that an Arizona company allegedly sold to doctors in 17 states under the guise that it was a less-expensive version of the muscle relaxant known as Botox. At least four people were reported paralyzed after using the substance.

During the Cold War, the United States, the Soviet Union, Iraq and several other nations produced vast quantities of ricin, botulinum toxin, anthrax and other agents for potential use in biowarfare. Not all stocks have been destroyed, however, and U.S. experts are anxious about the security of the smallpox cache in Russia.

Moreover, experts increasingly fear that terrorists may seek to replicate the genetic sequence of smallpox and other diseases. Researchers already have charted the DNA sequence of the variola major virus, which causes smallpox, and in theory it could be copied.

“A disease in the hands of a thinking enemy is very different than a naturally occurring disease,” said Daniel Hamilton, a professor at the Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University and a co-director of Friday’s exercise. It is “potentially as lethal as a nuclear attack.”

Depending on how a given disease spreads, it may be difficult to trace the source of a bioterrorism attack. FBI investigators still are unable to determine who mailed at least four letters laced with anthrax spores from Trenton, N.J., in September and October 2001. The disease caused five deaths and a near panic in the Capitol building, where two of the letters were sent. Senate offices were closed for weeks.

Although anthrax is far less deadly than smallpox, Americans remain vulnerable if another attack were to occur.

A federal court order in October stopped the U.S. military from inoculating troops against anthrax until further research is done. Even if approved, that vaccine requires six doses over 18 months to build up antibodies. A faster-acting vaccine, using gene transfer technology, is being tested on mice, but is at least two years from production for humans.

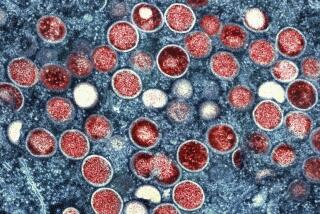

Smallpox, a scourge throughout history, is highly lethal and highly contagious. There is no effective treatment or cure, and epidemics killed hundreds of millions of people before global vaccination programs helped eradicate the disease in 1977. U.S. authorities stopped mass vaccinations in 1980, and many people inoculated in the past have lost immunity.

After the Sept. 11 attacks, the United States and several other nations produced and stored smallpox vaccines for their own populations. But most of the world remains unprotected. The World Health Organization, an agency of the United Nations, says it would take as long as 10 years to produce sufficient vaccine to slow a global epidemic.

That was the setting for Atlantic Storm, as Friday’s bioterrorism scenario was called. It followed other alarming war games over the last three years. Dark Winter simulated a biological attack on U.S. cities. Crimson Sky featured an attack on the U.S. food supply. And Silent Vector posited an attack on key energy infrastructure.

In this case, Albright served as U.S. president, supposedly chairing a transatlantic summit meeting with 11 prime ministers, when news arrived that vaccinated terrorists had dispensed dried smallpox at an airport in Frankfurt, Germany; in subway systems in Warsaw and Rotterdam, Netherlands; at New York’s Pennsylvania Station and Los Angeles International Airport; and at the Grand Bazaar in Istanbul, Turkey.

The largely ineffective response of the “leaders,” who huddled at a U-shaped table before 150 invited observers from the U.S. and foreign governments, exposed some of the likely problems real leaders would face in a bioterrorism assault.

As two giant screens blared fake news bulletins, and staff gave regular briefings of the mounting health and security crisis, the participants discussed whether to cancel schools and public gatherings, and to close airports and borders in hopes of curbing the epidemic’s spread. How would they enforce it? For how long? At what cost?

They bickered about whether to share their own limited national supplies of vaccine, and if so, with whom and when. They debated whether targeted inoculations of health workers and likely victims, or mass vaccinations, were more sensible. They argued over which institution -- the United Nations, the European Union, NATO or others -- was best positioned to lead a global response.

“Fortunately, we are not prime ministers anymore,” said Jerzy Buzek, who was prime minister of Poland during the Sept. 11 attacks and played the same role Friday. Then he summed up what he had learned in the daylong simulated attack:

“Nobody is ready.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.